Last week Adam Susaneck shared, through his popular Instagram account Segregation by Design, a picture of himself at the SXSW Conference in Austin, TX, standing with the acclaimed author Heather McGhee. It was a moment of emotion as she has inspired much of his work.

It was, too, a moment of reckoning for many of his followers, who hadn’t seen the face behind this one-man source visually documenting the destruction of communities of color in US cities. When Susaneck joined me in the virtual room four days before, he showed a friendly face, but it also caught me a little off guard that he is white.

His series of stark before-and-after comparisons and demographic data reveal the extent to which the American city was methodically hollowed out due to racist policies of redlining and highway construction. What started as an ‘atlas of urban renewal’, in the words of this architect, while earning his BA at UC Berkeley and MArch from Columbia GSAPP, has been lately picked by grassroot organizations across American cities, in particular BIPOC communities, as a reliable source for their causes.

Over two years, Susaneck, under Segregation by Design, has amassed colorized historic photography and put together digital maps to recreate the great architecture and public sphere Americans once had in their cities – and how they lost them.

With the support of his fans in Patreon, he buys aerial photos, which have been painstakingly put together by the dedicated team at historicaerials.com, an outgrowth of the University of Arizona in Tempe, AZ. He also uses public libraries for photos and other reliable sources. He rarely shows himself, and he tells me that he wants his research to speak for itself to the extent possible; something that, I believe, has reinforced the authenticity of his work.

And it has funneled the popularity of his account to the right cause. “I don’t intend to be the voice of The Bronx or the countless other affected communities, but rather translate my academic research into a digestible format to support local advocacy groups,” he explains.

Animated digital maps make it easy to visualize the rollout of urban highway construction through cities that separated communities, tearing down buildings and displacing people. The subject matter varies — from social justice, politics and environmental justice to land reclamation — but at the center of all of them lies an invitation to explore demolition in the name of ‘urban renewal’ and reckon with the consequences of history.

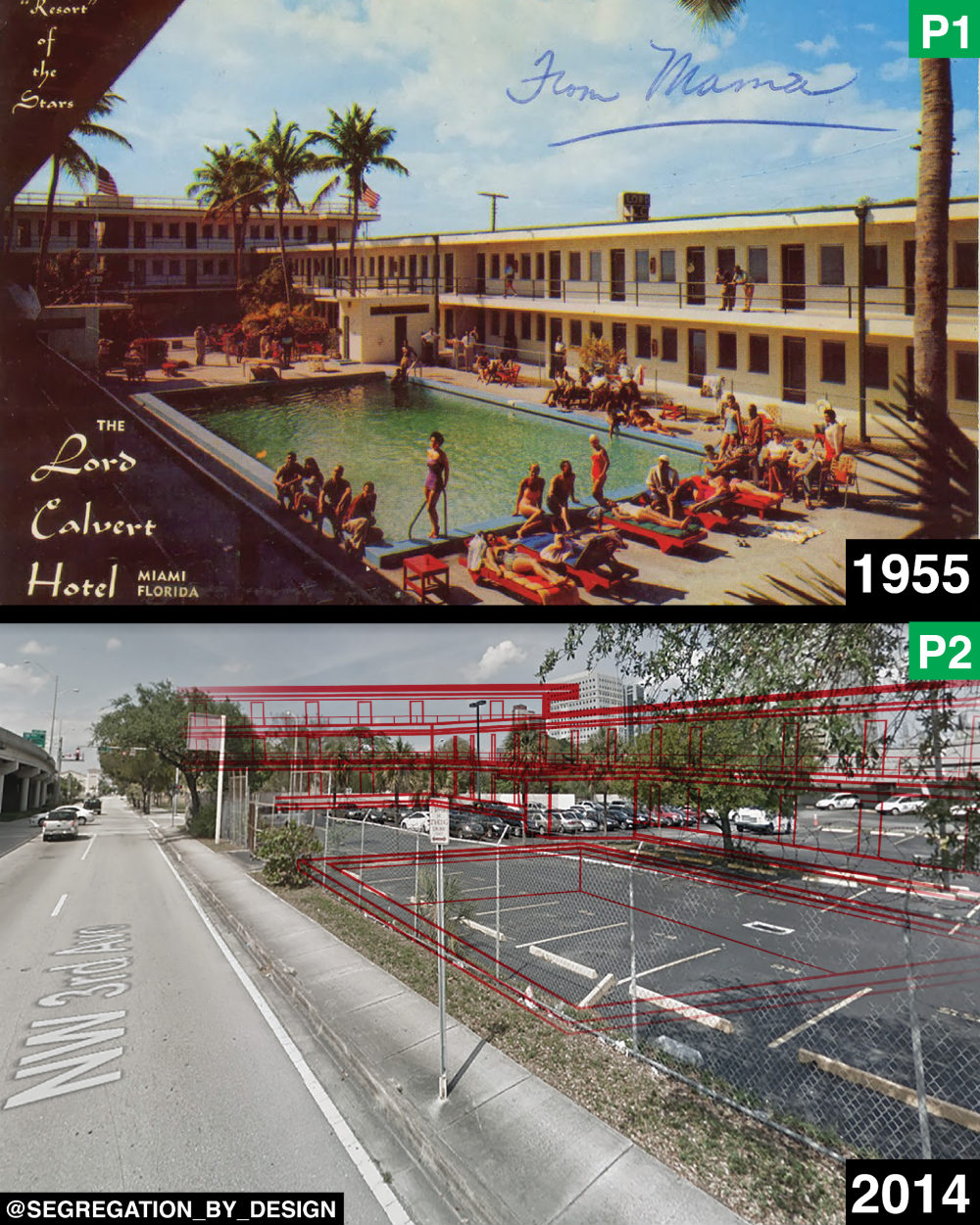

I told him that I am particularly touched by the postcard-like picture of a swimming pool at The Lord Calvert Hotel in Overtown, Miami, in 1955, which he shared in Segregation by Design. It turns out that pools have been the central metaphor of the book of Heather McGhee which inspired Susaneck and he strongly recommends: “The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together”.

We blew apart the whole idea of the public just to keep it whites-only

The hotel’s bustling pool appears along the photo of a parking lot (from google maps taken in 2014). “The hotel was demolished in the 60s during government-funded “urban renewal and slum clearance” and replaced by a USPS postal distribution facility,” explains Susaneck. It was a popular hangout for visiting artists and prominent Black leaders and intellectuals, also home to the popular nightclub Knight Beat, which throughout its history hosted Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Cab Calloway, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, Nat King Cole, and more.

But it wasn’t just the hotel. The construction of a highway destroyed part of the neighborhood of Overtown —which the city had officially deemed a “blighted slum”— displacing 12,000 residents nearly all of them black. When this happened, Overtown was a thriving neighborhood in Miami known as the “Harlem of the South,” owing to its strong local economy and entertainment scene. When the government passed the Federal Aid Highway Act in 1956, which provided a 90% federal match for interstate construction, the city of Miami simply didn’t want to save the neighborhood.

When I zoom into the hotel’s pool picture, I see black and white smiling faces at the pool. It is a case in point. “Racist policies were self-defeating also for white Americans,” says Susaneck. Public pools were common in American cities before the 1950 and most were officially whites-only. When the Supreme Court declared segregated access to public amenities (such as pools) to be unconstitutional, they suffered the same fate as the one of the Calvert Hotel due to the fear of integration. And Susaneck adds “we effectively eliminated a public common good and made it accessible for only those who could afford it,” referring to the popularity of the construction of backyard swimming pools in the 60s.

Another picture of a public pool buried under a lawn in Baltimore, with the stairs still ingrained in the ground, gives you a sense of the urgency some had to make the pools disappear. The same happened to public transportation and public schools, where not only black citizens were denied a public good, white citizens also long lost it to the past. “We blew apart the whole idea of the public just to keep it whites-only,” says Susaneck.

I find it interesting that he often uses “we” to refer to “US cities” that elucidates the complex relationship that many Americans currently have with their homeland. An architect who abhors the indiscriminate construction of highways that has overwhelmed his country, a fierce opponent who detests the conformity imposed by cities, he says he lends his research skills to activist communities “to help fix that horrible nature of our urban environment.” And he adds, “we sort of did it to ourselves.”

But he says he is in a difficult position himself. His research work occasionally is commissioned by a big infrastructure consulting firm, an opportunity that Susaneck sees to preach the mistakes made in the past, and advocates for better cities and save architecture, however he doesn’t always succeed in his endeavor.

Although I have been following Susaneck’s work for a long time, our paths crossed for the first time when I was co-writing an article for this publication about the advocacy work for environmental justice of a grassroots group in Minneapolis. Through Segregation by Design, I realized that some of the highways, which surrounded this community, were part of the most significant “urban renewal” schemes of any city in the US.

Under the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966, Minneapolis was chosen to participate in the “Model Cities” program. Far from becoming a model, “the middle of the city simply died, and Minneapolis is so dependent on cars that the city doesn’t care about environmental issues,” says Susaneck.

He believes old demolishing practices continue today in legal form. Developers and cities have weaponized the public debate of urban renewal and the much needed infrastructure, to give them credit to legally keep building or expanding free highways as a “common good for the public.”

Susaneck built the case in a recent op-ed article he wrote for the New York Times “Mr. Biden, Tear Down This Highway.” It refers to the group opposing the expansion of I-45N in Houston, an existing highway that would “forcibly relocate over 1,000 families and has already emptied the Clayton Homes, a public housing development built in 1952, which served mostly Black residents.”

A graphic reproduction of the destruction that the expansion of the highway would create, caused furore among his over 136 thousand followers on Instagram, with the number of views and shares going through the roof. Thanks to the work of advocacy groups like Stop Txdot I45 the city delayed the construction for a while. The Biden administration invoked Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits racial discrimination in any activity that receives federal funding. But the city has resumed the project.

Often the communities opposing freeways expansion are depicted as having been “slums”, but Susaneck’s material is being used in public hearings and other legal cases of land reclamation like @Whereismyland to tell a different story. Case studies like Bronzeville on the South Side of Chicago–known as the “Black Metropolis” due to its prosperity–reveal that many of the neighborhoods destroyed were anything but slums.

Last December NYC Mayor Eric Adams announced that USDOT has awarded the city $2 million to study mitigating the damage from the Cross Bronx Expressway. This progress was possible due to the tireless work of the grassroots group Loving The Bronx, as well as the entire community. In the announcement the Mayor office used a graphic from Segregation by Design.

Even if the South Bronx continues to be haunted by the ghost of Robert Moses, whose physical legacy includes the Cross Bronx Expressway, Susaneck says that “New York is a complex example and not as representative as other American cities. While a lot of the tactics were pioneered by Moses, the physical reality of New York made full-scale automobilization impossible.”

From his home in Downtown West Palm Beach, FL, he told me that soon he is going to leave the US for a Phd at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. I can feel his excitement. His research will continue to focus on American cities. And he says that he will continue to grow the followership of Segregation by Design through regular posting to keep raising further awareness and amplifying local voices in opposition to freeway expansion. Because in America, at the moment, it is still a matter of first seeing then believing.