When Martin’s Patershof church in Mechelen, Belgium, was transformed into a hotel “where guests will sleep, perhaps have sex in a church,” it raised some ethical questions, a Flemish regional minister reflected at that time, about this landmark repurposing project. But such holy hesitations shouldn’t distract us from the real ethical question: who is benefiting from repurposed churches?

Let’s start with how churches typically emerged in the first place. Historically, there was an initial gift or ‘beneficie’ which comes into question, but with time this fell into oblivion. In Europe, in exchange for a cure of souls or [any] other spiritual duties, assets such as land were given to the Church by believers, or by a monarch as a kind of aristocratic gift; in America, churches were built as a result of colonialism.

Subsequently, ordinary citizens have subsidized faith-based properties with donations and taxes. In Germany, for instance, 8% of one’s income tax paid goes directly to the Church, and in Spain, additionally, a property tax exemption has been granted to the Church.

And so now, as Priest/activist Graham Singh tells me over Zoom from Montreal, if churches are rented or sold to be repurposed, their investors — in other words, the local communities — could all say, “this is actually our property. You don’t have the right, bishops, to decide this on your own.”

Singh seems ready to respond to all the detractors, to all the criticisms of his assessment. His advocacy triumphantly upends the repurposed churches narrative, where economics have slipped. In St.Jax, Montreal, cultural activities including a circus have been activated inside the church; in Edmonton, three Muslim congregations share the oldest church in the middle of town; and in Vancouver, the Southside Church will be turned into 800 affordable housing units. For him the impact of repurposed churches has to be quantifiable in discounted rent affordability for families, if they are transformed into housing, or in discounted rent for outreach work, if the churches become community hubs.

Singh graduated from the London School of Economics in 2001, and joined The Church of England in London in 2013. With a business mind, and a holy heart, he saw the creaking infrastructure of houses of worship as a strategic opportunity to redeploy the historic land wealth of Canada’s faith communities into social return.

In 2018 he founded the Trinity Centres Foundation, a pan-Canadian charitable organization based in Montreal and a pioneer in church transformation across Canada with the commitment to create an equitable future for our cities, towns and villages. This year Singh has enrolled in an Impact Finance Innovations Programme, becoming the first social impact priest at Saïd Business School in Oxford. Yet he doesn’t see a conflict between his mission and the spirituality he represents.

“Monastic leaders, nuns and monks, priests and pastors, have been involved in social change for as long as there’s ever been the Church,” he says with a smile. He cites examples like Mother Teresa and Martin Luther King, Jr. “Look at William Wilberforce, a British politician, who became an evangelical Christian and the leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade in England. These were all religious people,” he reckons.

***

Since its birth, the Church often went through times that signaled moments of reformation. Singh takes me through some of the milestones in Christianity. During the first 300 years, Christians were rather an underground movement. It is only from Emperor Constantine onwards that the Christian religion intertwined with political power, and took control of urban land; markets, housing and wealth were built around churches and cathedrals.

By the 16th century, there was a huge rebellion inside the Catholic Church, as the European Reformation condemned bad Christian governance and posed a political challenge to the papal authority. Led by activists such as Martin Luther and Jean Calvin, the Reformation split into two main branches: the Magisterial Reformation which took over Catholic land assets such as parish churches and monasteries; and the Radical Reformation which refused to touch any of what they saw as tainted goods – they left the cities to establish separate communities of the ‘pure’ or ‘set apart’.

Both these ‘Puritans’ and what became ‘Protestants’ then formed the new unholy alliance of colonialism. Reformists joined the European colonial enterprise and expanded their teaching to America. “And now you have an indigenous problem all over, coming together with slavery, and even with forced migration of workers. And this is all tied into the religious story,” wraps up Singh.

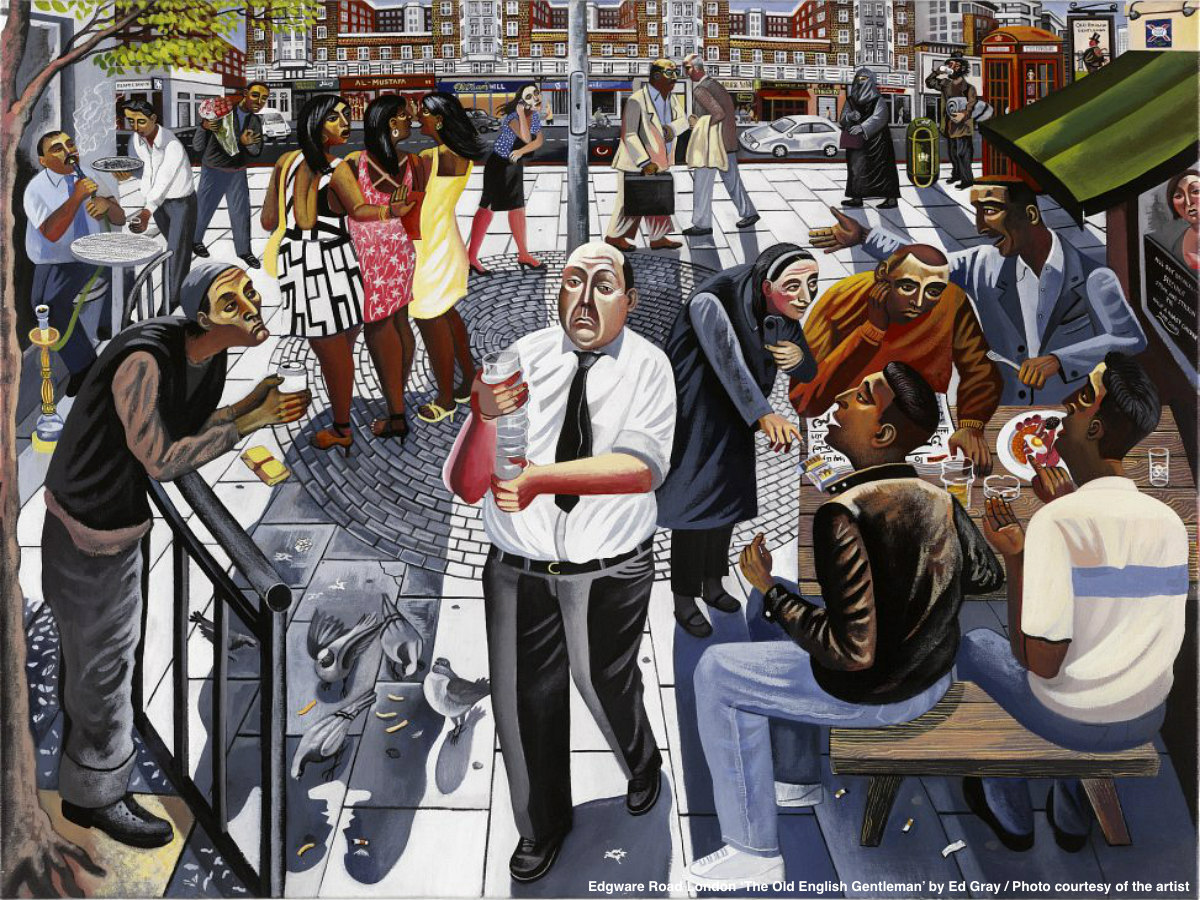

In his view, 500 years later, we are at another moment of reformation. With hindsight, Singh might end up being right. Two weeks after I spoke to him, the Cardinal, who oversaw the management of Vatican funds from 2011 to 2018, was sentenced by the Vatican’s criminal court to five years and six months in jail due to embezzlement in what the Italian media had dubbed the Catholic Church’s “trial of the century”. The charges are related to the alleged misuse of Church funds in an ill-fated London property investment, and the fact that the Church was investing in luxury real estate raised more than a few eyebrows. And this was not just any property. The estate was located in one of the upscale neighborhoods in London, often criticized as ‘ghost towns’ due to foreign owners who ‘buy to leave,’ hurting local communities, businesses and fueling housing prices.

Singh suggested, “We have to look again at the ownership of religious property and realize it’s actually working against our religious objectives. So when I’m speaking to religious people, I’m saying, ‘don’t you see that this is a weight around our neck which is killing all the churches?’” He reminds me that the use of power is a long story, but it’s an important one. In North America there has been a slow but rude awakening to the damage done by colonialism — the conversation over slavery taking center stage — while in Europe the financing of the Church, direct and indirect, serves as an important critique of a blurred relationship between State and Church.

“The tax system, I think, is gonna catch them [Europeans] up,” says Singh. Given radically declining churchgoer numbers in Europe, “this social contract is out of date,” and especially in countries where an increasing number of taxpayers with different faiths could start questioning why they are only financing churches.

***

In Canada there’s a natural opportunity to consolidate a new property model because Christians overbuilt churches. Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, Catholic, Lutheran and all of the colonizing churches, fought to build the grandest and tallest buildings in the ‘New World’ in order to prove their colonial prowess. Compared to overcrowded Europe, cities in North America had much more land and less population density, and as such, this overbuilding process contributed to what became an awkward urban sprawl. So “the adaptive re-use of faith properties offers an exciting opportunity to connect with a new urbanism,” says Singh.

Singh’s enthusiasm wanes with his acknowledgement of the natural market forces at work. He’s well aware that developers “will just pick these properties off and turn them into condos.” But there are opposing forces thankfully working as well: large institutional funds are beginning to look for ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) investments. It is very challenging to get a return on investments like a homeless charity, or a food security group, or a grassroots organization working with indigenous people, but “churches are real assets that could be the home for all of these projects.”

So Singh and his team have created a new ownership structure that could actually allow the Church to recapitalize the properties, get a social and financial return for investors, and a discounted rent for communities. Not least for the health of the Church.

They have worked on the design of a non-religious fiduciary trust, set up for the specific purpose of holding the ownership of faith-based properties, jointly with civic society. It acts like a community land trust, but on a national scale, which could also work with nested local community land trusts. Since repurposed churches would be off market, this national community land trust cannot borrow on a mortgage secured basis, unless in its design, the State leans in with a government guarantee. In that case, they’d create a bankable trust which can borrow money and hold the ownership of the properties. “This model allows a first level of capitalization to get these buildings up to a basic code, like fixing the roof, the masonry, the heating system and other basics.”

The next level would be to scale up this model to 1,000 repurposed churches, a feasible size for institutional funds and financial institutions in Canada. In terms of revenue, there is a hard line in the design between the for-profit side for institutional investors, and the not-for-profit side, for tenants and the Church. Tenants inside the repurposed churches must pay rent, equivalent to the operating expenditures. But if they want to transform the space into a theater, refugee center or offices, they need to pay for these capital improvements–something they usually do already using the funding from the philanthropic sector. The property can’t ever be sold.

“Real estate investment structures are extracting too much wealth from local communities. And those structures, I believe, are the next in line to be hit by the global activist community,” says Singh. He compares it to climate change arguments, which all of a sudden, became mainstream. “And we’re going to realize we need space for the nonprofits, the charities, the arts groups; we have undervalued them. We haven’t understood that cities only work when those things are thriving, and if they don’t, cities fail.”

It goes without saying that there are many underutilized faith-based because Christians have stopped going to church. For Singh the big turning point was the Second World War, and the ideologies of the materialistic 50s and the defiant free love 60s that ushered in a revolt against the Church across the Western world. “Then we entered into a stage where we thought that the State can solve all the social problems because people have left the Church behind. Now we have realized that the State cannot solve them, not because it doesn’t have the money, but because it’s not good at it.”

Collectively governed, instead of religiously governed, these repurposed churches could yield many collateral benefits, building bridges between faith, government, finance and ordinary citizens. People of different political leanings, and faith– Jews, Muslims, Catholics and so on – could share the same building, creating unusual encounters, and adding another layer of social impact.

For Singh this is a great opportunity for the Church to become a safe place for people to figure out what they believe, and rediscover spirituality. “But religious adherence is something of the past, and when you look at Jesus’s life in the Christian faith, you will see that he wasn’t interested in religious adherence.”

So yes, the traditional church has been emptied out, agrees Singh, “but the new spirituality is on the rise, and if the Church, with its old resources, gets things right, it could actually be fertile soil for that renewal.”