Researchers in Chiang Mai, the second-largest city in Thailand, are working against the clock to document ordinary life in archives. The neighborhood of Wua Lai in the south of the old city, which flourished thanks to Burmese goldsmiths and craftsmen known as the “silver village”, is disappearing due to rapid urban transformation. The city’s growth has threatened entire neighborhoods before heritage permeates through generations.

Far from Chiang-Mai, in Jerusalem, the Maghrebi neighborhood had a similar fate. Dating back to the late twelfth century, this neighborhood and its religious endowments offered housing to pilgrims of Maghrebi origin for eight centuries. In 1967, it was destroyed to make way for an expansive plaza in front of the Western Wall.

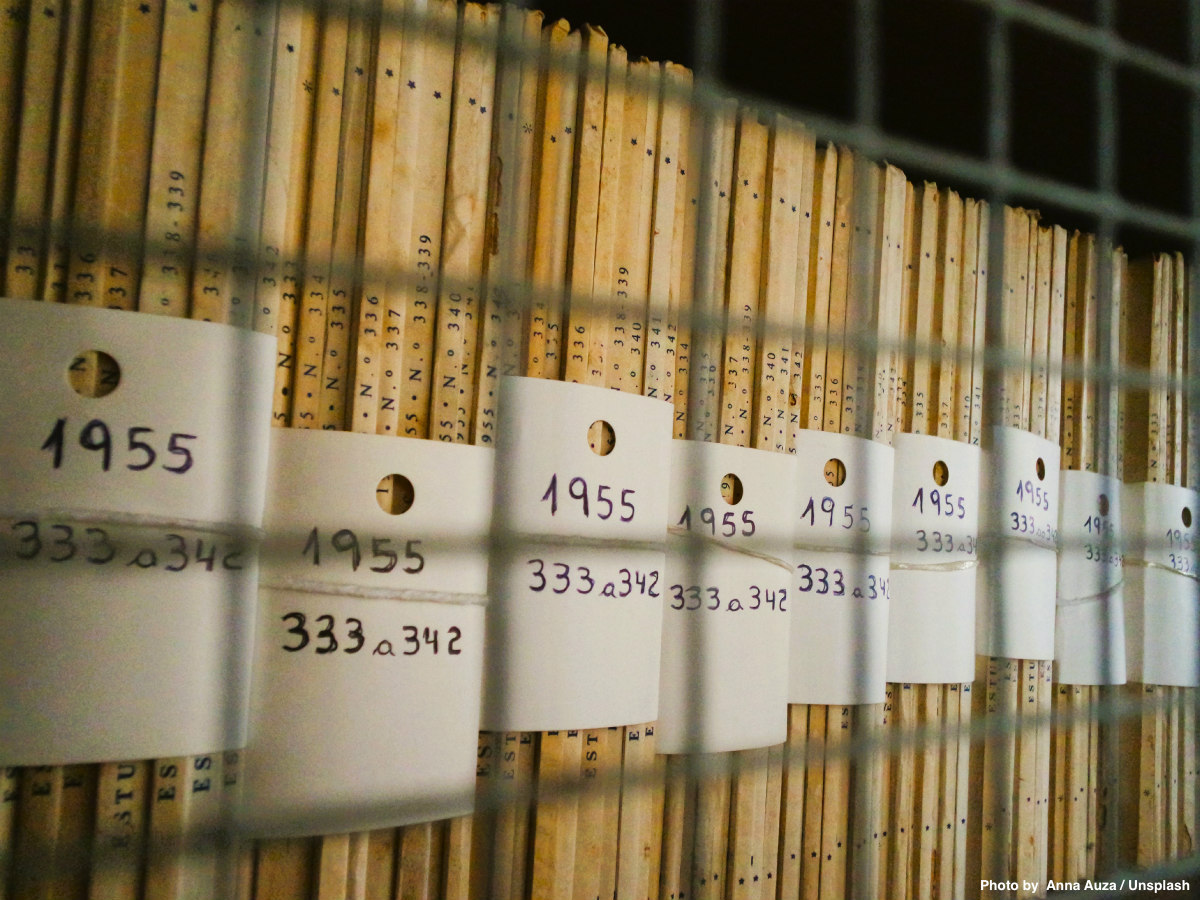

It might be venturesome to say that, perhaps, those neighborhoods served a better city before they disappeared, but there are surely experiences that could be drawn on and shouldn’t be forgotten. City archives act as guardians of the past, but they also evoke a sense of exclusivity, preserving information that remains hidden from the public. Depending on their setup and institutionalization, archives can be accessed and used in specific ways, or their contents may not be open to everyone. And so archives have the power to hold knowledge of our collective memory.

In some cultures, such as in Chiang Mai, the agency to inform the present relies on people. Unlike in Western cities, the transmission of individual and collective memories in Southeast Asian cities is based on oral history and written on non-permanent materials (latanier palm leaves). But rapid urban development is stepping on the heels of historical documentation.

Without identifying, describing, and digitizing these memories in city archives, soon no one in Chiang Mai will recall the local techniques and how urban life around craftsmanship was in Wua Lai. This time, race is a big concern among researchers and citizens alike. They recognized the need to develop alternative notions of “ordinary heritage” and proposed development plans to help preserve neighborhoods. In Jerusalem, researchers were left with photographs, archaeological artifacts, and minutes of municipal meetings to reconstruct the splendor of a neighborhood that has been a refuge for Maghrebi pilgrims for many years.

Researchers in Chiang-Mai and Jerusalem are part of a multi-disciplinary team under ARCHIVAL CITY, a project launched by the Gustave Eiffel University and funded by I-SITE Future, which brings together historians, architects, and more to sway city archives with the savvy idea “to imagine, debate and plan the city of the future by incorporating robust data from the past.”

“We are proposing new ways of accessing, viewing, and using city archives and building a much-needed bridge between those who are interested in the city’s past and those creating a more sustainable future,” explains Annalaura Turiano, a historian of contemporary Mediterranean and Middle Eastern history, who is responsible for the dissemination and publication of ARCHIVAL CITY. And she adds, “With the project we want to show how cities could produce, sort, conserve and use the archives related to the city more inclusively to respond to certain current challenges in urban development.”

ARCHIVAL CITY has its roots in the project Open Jerusalem Archives led by Vincent Lemire, a Professor of contemporary history at the Gustave Eiffel University and director of the Centre de recherche Français à Jérusalem (CRFJ). Using a complex documentary archipelago, a group of researchers strove to create a catalog that could mirror Jerusalem’s history through the exchanges, interactions, and sometimes hybridization between different traditions. Funded by the European Research Council and with the support of the French National Archives and the Gustave Eiffel University (previously Université Paris-Est Créteil Val-de-Marne) in Paris, this project demonstrated its unbiased openness to all demographic segments of the Holy City’s population.

With this project, we aim to demonstrate how cities can produce, sort, conserve, and utilize archives related to the city more inclusively, thereby responding to current challenges in urban development.

In 2019, Lemire and his team brought this ambition to write history more inclusively to ARCHIVAL CITY. Using a network of like-minded researchers already established between Jerusalem and Paris, the team broadened its mission to include the cities of Chiang Mai, Algiers, Bologna, Quito, Greater Paris, and Jerusalem. More than fifty researchers from various countries and disciplines engage in providing data to an open online platform “to be used not only by researchers, historians and archivists, but also by local government, policy-makers and urban operators, as well as citizens eager to take part in their urban environment.”

A point in case is how the documentation work done in Chiang Mai has inspired collaboration between researchers, grassroots organizations, and the local administration for the carpenters’ district in Bangkok to open a space for negotiation in urban planning processes. In Quito, archives of local sport clubs of “Andeanism “(a term not existent in English but describing the equivalent of “Alpinism “, the mountain sports in the Alps, for the Andes) retrieve the history of the city with its natural environment, given the continued threat of natural disasters, and its resilience through the urban sociabilities of this sport.

Often these community archives, also referred to as “grassroots archives”, are not easy to access; at times, they are kept in their own record of families, explains Turiano. Yet they play an important role in constructing counter-narratives that challenge the dominance of histories produced by mainstream archival institutions. Access to private archives sometimes depends on personal ties and engagement. Jeroen Derkinderen Lombeida, PhD student and a member of the ARCHIVAL CITY, explains in a reflection on his research about Andeanism: “As I am part of the andeanist community, I had no difficulty in accessing the archives of the associations and clubs; from the 1960s onwards, there were a dozen clubs, some of which no longer exist, but many are still active.”

Despite their specific contexts and approaches, pressing issues such as rapid urbanization and environmental risks are common threads among most of the cities selected in ARCHIVAL CITY, including the issue of power. “Archives are a way of resistance, but also a way of exercising power”, says Turiano. At times in history, archives abused their authority to underpin assertions about the past and shape the present.

In Algiers, archives were used to reproduce and manifest social inequalities during colonial times, as the population and its daily life in the neighborhoods were not well-documented or remained unidentified in municipal archives. The team from ARCHIVAL CITY in Algiers is now working on how to access archives that were destroyed, dislocated, and often privatized after colonization, which may hold information on the people and their neighborhoods. In the case of the city of Algiers, the information is scattered between France, Algeria, and other Mediterranean countries.

In Bologna, with the use of one of the oldest and best-preserved urban archives in Europe, dating back to the end of the 13th century, containing legislative sources, accounts, tax lists, and private sources (ricordanze books) of important families, the ARCHIVAL CITY team has been able to show that taxation documents were a tool to reproduce social and political inequalities. As Clement Carnielli (a member of the Bologna team) explains, “this did not result in a total deprivation of rights, but encouraged a feeling of belonging and collective actions claiming the redistribution of public wealth.”

ARCHIVAL CITY has demonstrated that city archives – whether public or private – store valuable information about a city’s past, enabling a more holistic and inclusive approach to writing history. This robust data is crucial for establishing sustainable ways of city planning and urban development. In more practical terms, the team uses the open data platform AtoM for archival descriptions. They have developed a framework and specific tools for describing, managing, and utilizing various archives to make research processes more accessible and transparent.

As language is often a restricting factor for conducting archival research – you must know the respective language to understand the sources – ARCHIVAL CITY presents the data descriptions in both the original language and English. This allows more people to gain an overview of the data available in a specific context. The representations of the data range from a video game set in Quito during Inca times to the reconstitution of a medieval archive in Bologna and a 3D modeling of the Maghrebi neighborhood in Jerusalem.

Although the funding period will end in 2023, ARCHIVAL CITY plans to continue its work permanently as a “living archive” to create inclusivity in urban research and sustainability in future city planning. This also means opening up data collection to various aspects of city life, including ordinary techniques and practices, oral descriptions, and “lost knowledge” outside of dominant archival practices. Only by considering this data as well can we understand comprehensively how the past informs future urban projects. Or as Annalaura Turiano puts it: “We should consider the whole city as a living archive that connects the past to the future.”