Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

Step into the homes of writers, artists, and thinkers where discussions and debates nested democracy in our cities—and be part of today’s conversations at these historic locations.

Writer Vernon Lee was ahead of her time, but credit arrived much later, Federica Parretti explains as we explore the collection of her books in the old library at Villa Il Palmerino in Florence. Parretti’s grandparents, artists Federigo Angeli and Carola “Lola” Costa, bought the house from Vernon Lee; Costa kept her admiration for the writer as her “little secret garden.” After her grandmother passed away, Parretti opened the house to the public, transforming it into part of the city’s infrastructure of thought, emphasizing its legacy rather than its prestige.

Born Violet Paget in 1856, Vernon Lee adopted this pseudonym as a writer and moved to Florence in 1889, when it served as the capital of cosmopolitan intelligence in the Novecento. During this time, Florence was “Europe” in miniature. Intellectuals flocked to the city precisely to live outside national identity while still being immersed in culture. Many renowned writers, including Elizabeth von Arnim, Virginia Woolf, Oscar Wilde, Henry James, and Bernard Berenson, passed through Lee’s home. The list is long.

Parretti and her husband have been researching these intellectuals by examining records of Vernon Lee’s correspondence and her books. When her grandparents acquired the villa, only an umbrella remained; the rest of the belongings — books, letters, documents, and paintings — were all gone.

Every Thursday, Lee hosted a literary salon at Il Palmerino. An engaged feminist, she was related to British suffragist Alice Abadam. Lee wrote short stories and essays and was regarded as an authority on the Italian Renaissance. Only recently has she gained recognition as a feminist writer due to the #MeToo movement. However, Lee was even more pioneering in the fields of psychology and neurology, anticipating ideas that would later become central to cognitive science, affective neuroscience, and empathy studies — before the scientists.

Interestingly, she also foresaw concepts such as affective urbanism and “neuroarchitecture.” Lee argued that buildings and plazas can “teach” the body how to move and feel and explained why some streets feel oppressive and others liberating. She viewed the city as a nervous landscape — architecture as an emotional stimulus. More remarkably, Lee connected internationalism to a mindset characterized by nervous and imaginative openness, asserting that nationalism represented a contraction of imagination — a “psychic narrowing.” This perspective offers an extraordinarily modern psychological framing of political identity.

It is challenging to determine who gathered at her house during that time. Parretti notes that since Lee spoke five different languages (English, French, Italian, German, and Polish), she interacted with numerous intellectuals who visited Villa Il Palmerino. They were not merely exchanging news but co-developing ideas. In some instances, Lee established lasting friendships.

In 1896, German writer Irene Forbes-Mosse moved to Il Palmerino with her second husband, the English Colonel John Forbes-Mosse, and lived there together for ten years. With the outbreak of the First World War, Forbes-Mosse returned to Germany and corresponded regularly with Vernon Lee. Their surviving letters illustrate how two women, outside formal institutions, built a transnational space of thought. During this time, Lee was developing her ideas on the psychology of art, specifically the concept of Einfühlungstheorie (empathy theory). The letters reveal Lee testing these concepts informally with Forbes-Mosse before they appeared in her essays. This has led scholars to argue that Forbes-Mosse was not merely a passive listener but a conversational collaborator in Lee’s education about the aesthetic movement.

The Lee-Forbes-Mosse correspondence itself wasn’t widely circulated, but the intellectual world it sustained reached American women and helped shape the Anglo-American female “aesthetic cosmopolitan” milieu, especially for American women living, traveling, or studying in Europe. American women writers, patrons, artists, and reformers regularly visited Vernon Lee and her circle. Lee’s ideas — refined in letters to Forbes-Mosse — later appeared in essays and lectures read by American women.

For instance, American writer Edith Wharton was not particularly close to Lee but was intellectually influenced by her cosmopolitan stance and the aesthetic debates circulating in Lee’s salon. There is also correspondence with American philosopher and psychologist William James, which may have influenced him, as Lee was already elaborating on the German concept of Einhülung. Notably, Parretti points out that there was considerable networking within their letters, and certain references are explicit, such as James introducing Edith Wharton to Lee. Lee even exchanged letters with Sigmund Freud, motivated by her brother’s recovery from hysteria syndrome and her ongoing interest in psychology.

In an increasingly nationalistic early 20th century, Lee continued to advocate — both culturally and politically — for a cosmopolitan Europe, pacifism, and artistic integrity. However, this stance cast a shadow over her persona. While her acquaintances were often engaged in military support, she remained a staunch pacifist and opposed the war. “She said, I can help the civilians, the children, the women, but don’t ask me to help the soldier, any soldier,” explains Parretti. She lost many friends and was partly rejected by society until she died.

Lee never met Parretti’s grandmother, Lola Costa. Both women were British; Lee was born in France to British expatriate parents, while Costa was born in England to a French mother and an Italian father descended from the counts Costa di Carmagnola. Costa faced challenges as a young woman after her parents separated, ultimately painting in Paris to support herself.

Recommended Read: Open Houses #1: Monacensia Hildebrandhaus, Munich

At the end of the 1920s, Costa arrived in Florence to teach English at the Berlitz school and became a private tutor for the artist Federigo Angeli. As the popularity of Renaissance art surged in the United States during the 1920s, American clients increasingly sought out his work. Angeli painted frescoes in the Florentine style for monumental residences designed by American architect Addison Mizner in Palm Beach, Florida, as well as for private homes of wealthy clients, who demanded both originals and reproductions in large quantities.

“My grandparents fell in love because there was this art connection. They were both painters,” explains Parretti. They married in 1932 and three years later purchased Villa Il Palmerino from Vernon Lee, the year she passed away. Costa had the same English-speaking doctor as Vernon Lee; he mentioned to Costa that Villa Il Palmerino was on sale. “My grandmother wrote in her diary that from the moment that she stepped inside the gate she immediately felt at home because of the English garden, the blue bells, and all the flowers from her beloved England,” explains Parretti.

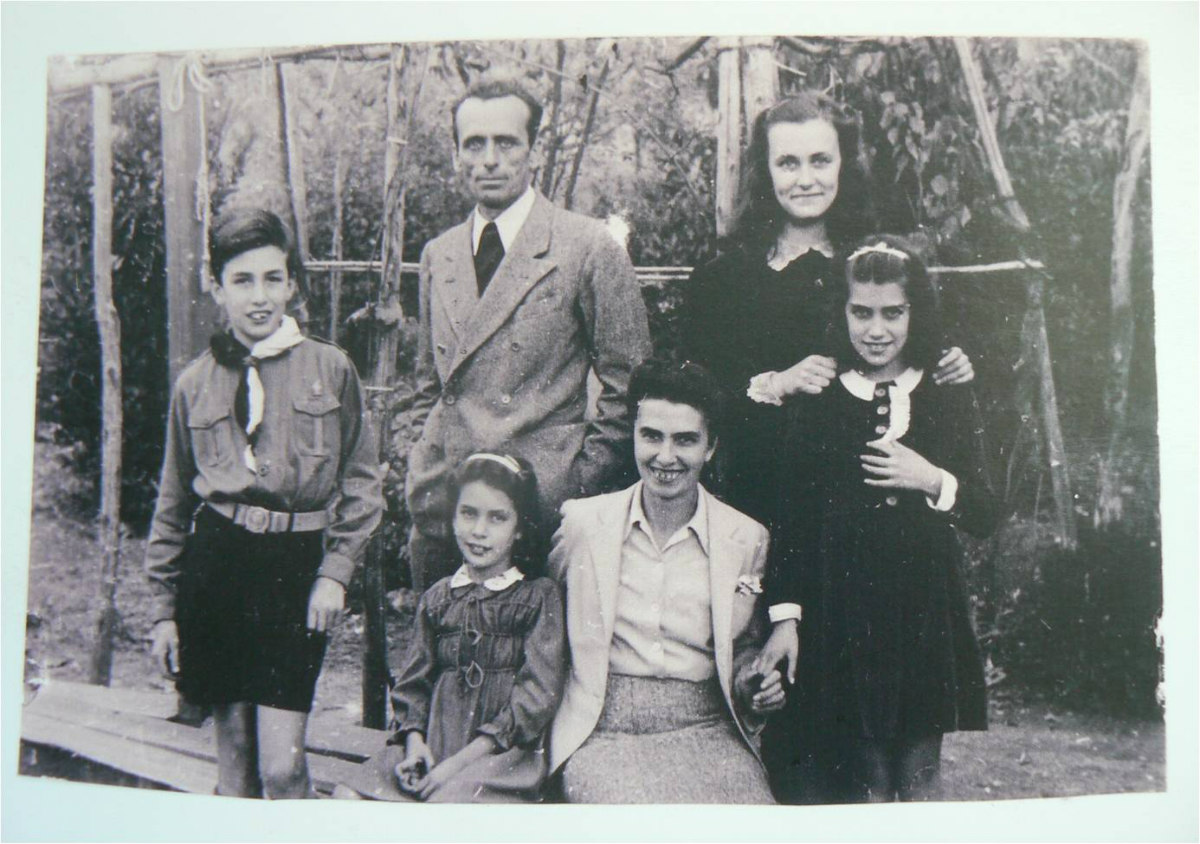

The house became their studio and residence, where they raised their three children. During this period, free from pressing financial needs, Angeli and Costa painted numerous works, including portraits, still lifes, and landscapes of the garden and Tuscany around the Villa.

***

The foundation of Il Palmerino dates back to medieval times in Florence. In the 14th century, it was a small guard tower on the old path between Bologna and Florence, from where a soldier would guard the northern part of the town. If he spotted danger, he would signal with smoke to another nearby tower, and so on, until the message reached Florence. Later, during the Renaissance, the 16th-century Italian painter and architect Giorgio Vasari referenced the house in his well-known book, Le Vite de’ Più Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori, e Architettori (in English, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects).

According to Parretti, two brothers, both artists — Ottaviano and Agostino Di Duccio — lived in the house and worked for the Medici family. Agostino was a famous sculptor whose work can be found at the Opera del Duomo; he is believed to have started the large marble statue of David by Michelangelo. His brother was a jeweler and goldsmith who collaborated with the renowned painter Antonio Pollaiolo.

“This is the origin of the house,” says Parretti. “I think it’s interesting because there was already art happening here — what you might call art karma.” Parretti grew up in Il Palmerino until she was 14, when she moved to Northern Italy. After her mother passed away, she decided to return to Il Palmerino to “understand the history of this place,” she explains. “It was complicated to maintain a property that is so old, but we decided not to sell it and opened it to the public as a small Bed and Breakfast in 2005.”

Guests began to arrive, and intriguingly, many of them were artists. After two years of running the B&B, a photographer who was a guest invited John Paul Fusco to the house. Fusco was an American photojournalist best known for his photographs of Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral train, the 1966 Delano Grape strike, and the human toll of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

“That experience was a turning point for us,” says Parretti. She organized a workshop for young Italian photographers, who came to the house to show Fusco their portfolios. “It was fantastic—a great way to promote Italian photographers, serving as a significant reference for them. That was ten years before he died, and having him there was quite important. We realized that this was our path.” And so, Parretti and her aunt Beatrice, along with many family friends, founded the Associazione Culturale Il Palmerino.

Parretti and her husband began digging deep into the history of their house and discovered the significance of Vernon Lee that Parretti’s grandmother had kept for herself. “My grandmother never shared anything about Vernon Lee with her family — neither her children nor her husband. She was profoundly in love with Lee, read all her books, and even dressed in a style very much like hers. Perhaps it was a difficult assimilation for my grandmother; she was very Catholic and conservative, while Vernon Lee was an open lesbian,” says Parretti. After her grandfather passed away early, her grandmother was left alone with four children and struggled throughout the Second World War. Despite facing financial distress for a long time, she never sold the house.

Parretti is one of the six third-generation owners of the house, she explains as we stroll through the garden and admire the beautiful villa that comprises three separate residences. Several members of the family live in one of the houses, while another is where all the gatherings, events, and exhibitions take place, and where all Vernon Lee’s books are stored. This house was once an old warehouse, where his grandmother used to store, over winter, the ancient lemon trees that Vernon Lee planted.

The third house accommodates participants in the association’s residency program, featuring eight small apartments, each with its own kitchen and living room (some rooms share these facilities) at a reasonable price. In Florence, housing prices have been steadily rising. These apartments are utilized by artists, writers, or scholars who are fellows at various universities in Florence or are on sabbatical. Residents pay for their stay, which allows Parretti to sustain the association and reinvest in cultural activities. Additionally, they have support from a private donor in England, the Calliope Arts Foundation. Its mission to promote the recognition of underappreciated contributions by women in the visual arts, literature, music, and social history in Florence, London, and beyond aligns perfectly with Il Palmerino.

Every year, Parretti selects residents from the numerous applications she receives from artists (both male and female) worldwide. Applicants present the projects they will undertake during their stay at the house, and Parretti finds a good, diverse mix of individuals from different disciplines. “I learned from Vernon Lee the significance of connecting different fields. That’s where the most interesting things can happen. It’s exciting to have someone in political science alongside a musician or a writer in the house,” she explains.

Over the years, Parretti and her husband have built a large community around the house. They hold an internal dinner every week to bring people together. Additionally, residents showcase their work through exhibitions or lectures, inviting others from Florence to attend the events. “It is open to everyone,” Parretti expresses proudly. “Our neighbors are also very involved with the association. We often cook together for catering after events. Many members of our community are retired, especially women living alone, so it’s even more vital for them to come together and socialize. After a talk, we always enjoy a little aperitivo.”

The family has granted Parretti the right to use this part of the villa for a period of 15 years. Three years remain, and she is uncertain about the association’s future. “We don’t know what will happen. I hope I leave a strong memory of the place,” she says.