Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

Watsonville, California, presents a patchwork of colorful fields when viewed from the air. Located on the ocean side of the Santa Cruz Mountains in the Monterey Bay, not far from Silicon Valley, this agricultural town boasts one of the best mild climates for farming, with warm days that cool off at night.

In the United States, Watsonville is well-known for its berry production, while the rest of the world would rather recognize the name Driscoll’s. The town’s agricultural roots date back to 1849, when a butcher from Alsace, France, settled in California and eventually began farming near Watsonville. The butcher’s son, Joseph “Ed” Reiter, and Reiter’s brother-in-law, Dick Driscoll, cultivated their first strawberries in California’s Pajaro Valley in 1870. The fertile land allowed for continuous fruit production over several months, enabling families to settle in one location and work, rather than following in-season crops around the state.

In the 1970s, strawberry farmers in Watsonville began growing and commercializing raspberries and blueberries on a larger scale as Driscoll’s expanded internationally. Meanwhile, in Europe, people were foraging in the forests for the precious wild berries. By the 1990s, farm-grown forest berries began reaching Europe, and people put them on their tables without ever setting foot in the wild. This marked the beginning of the democratization of wild berries — nowadays from Watsonville to Dubai.

Adam Scow, co-founder of the Campaign for Organic and Regenerative Agriculture (CORA), explains over Zoom, “You can see fields in Watsonville that look like chocolate cake, with dark, rich, healthy soil. Others are more yellowish, dusty, and the soil is blowing all over the place. The first type represents organic fields, while the latter uses pesticides.”

Adam Scow’s grandfather emigrated from Mexico to work on farms in Pajaro Valley many decades ago. As early as the 1950s and 1960s, farmers began increasing berry yields by using pesticides, leading to a significant boost in overall field output. And so, berries became a more lucrative crop worldwide. “In the fall, farmers usually fumigate the soil and use these gases before planting the berries. But it doesn’t stop there. Throughout the growth of the bear, they’ll use different kinds of pesticides to spray on, like malathion and cypermethrin, which are also carcinogens,” explains Scow.

One of these pesticides is chloropicrin. In agriculture, this chemical compound — currently used as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial, fungicide, herbicide, insecticide, and nematicide — is injected into soil before planting a crop to fumigate it. In the First World War, it was used as a poison gas and has been recently in the news because of allegations regarding its use by the Russian military during its ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

In Europe, the use of chloropicrin in agriculture is banned due to concerns for human and environmental health, following a scientific evaluation by EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and the Member States. Chloropicrin is toxic upon inhalation and causes severe eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. Additionally, there are potential genotoxic effects, as some studies have indicated that it could cause DNA damage, raising concerns about its long-term safety.

Although the use of chloropicrin and other pesticides to prevent plant diseases is strictly regulated in the European Union, trade in fruits and vegetables grown with banned substances from third countries is permitted, provided they do not exceed certain maximum residue limits. But chloropicrin is volatile and breaks down quickly — that makes it less likely to show up as a residue on fruit (but not impossible depending on use).

In the United States, Chloropicrin was first registered in 1975. After being under review during the 1980s and 1990s, it was re-approved in 2008, with the EPA stating that chloropicrin “means more fresh fruits and vegetables can be cheaply produced domestically year-round because several severe pest problems can be efficiently controlled.” Notably, European companies are the primary sellers of chloropicrin and other pesticides in the United States. To ensure chloropicrin is used safely, the EPA requires strict protections for handlers, workers, and persons living and working in and around farmland during treatments. Protections include training certified applicators to supervise pesticide application, the use of buffer zones, posting before and during pesticide application, and fumigant management plans.

“There has been ongoing pressure for better notifications from Driscoll’s and farmers regarding the use of pesticides, along with certain restrictions—such as limiting applications to weekends at night. However, these measures do not adequately address the larger issue. The significant problem is the presence of these invisible gases in the environment. They can drift across the valley and remain in the air for up to 72 hours, or three days,” explains Scow. “There is no specific season; it is a continuous issue.”

In response to these concerns, a grassroots group of about a dozen experienced activists launched the Campaign for Organic and Regenerative Agriculture (CORA) in 2021, supported by the non-profit Center for Farmworker Families. Their goal is to protect the health of the Watsonville community, particularly the well-being of children, and the entire Pajaro Valley.

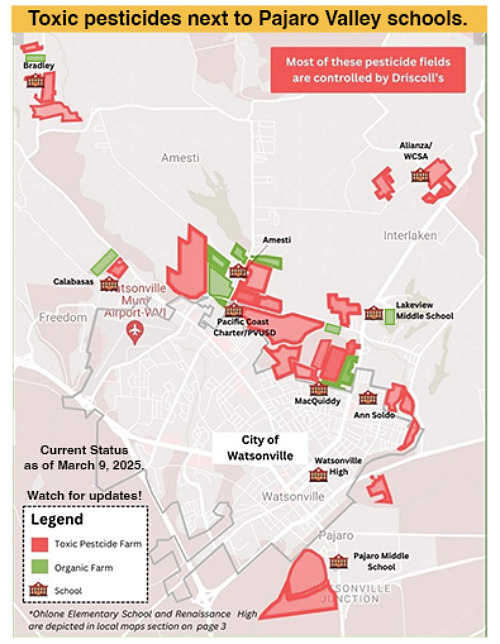

Scow teaches music at a school located next to fields where pesticides are used, and there are thirteen schools in similar situations. The quest for higher crop yields to feed growing urban populations comes with significant risks for frontline communities living in proximity to industrial agriculture. “The urban and rural landscapes have become a continuum,” says Valerie Bengal, a physician specializing in Family and Community Medicine with expertise in environmental health. With 34 years of experience working in county and community hospitals and clinics in the Salinas and Pajaro Valleys, she has witnessed the health impacts of industrial agriculture on these communities firsthand.

According to the National Cancer Institute, the pediatric cancer rate for children 0-14 years old is the second-highest in Santa Cruz County of all counties in the state. At 22.6 childhood cancers per 100,000 children, the rate in our county is more than 38% above the overall California rate of 16.3 between 2017 and 2021. Valerie Bengal explains that the epidemiology of pediatric cancer has been extensively studied worldwide. Numerous studies indicate that genetic traits and environmental toxins can initiate cancer, even before birth. Children and pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of toxins, and adverse effects on men’s reproductive systems can also impact their children.

The UCLA Fielding School of Public Health has identified 13 pesticides correlated to the onset of childhood cancer between birth and 5 years old when the mother lived within 2.5 miles of these pesticide applications while pregnant. An average of 3,020 acres were treated with these childhood cancer-linked pesticides in Santa Cruz County between 2017 and 2021. Earlier this year, a study in Nebraska found the strongest associations with childhood cancers from two pesticides not identified in the UCLA study: dicamba and glyphosate. Adding these two toxic chemicals would bring the average childhood cancer-linked pesticides used in our county to 5,060 acres per year (about 8 square miles). Because any woman working in the fields could be pregnant, the safety standards must be strict enough to protect everyone. In addition to cancer, diseases such as asthma and neurodevelopmental disorders have been devastating in our farmworker communities.

Recommended Read: A Surprising Tool for City Parenting: The Landline

In industrial extractive agriculture, it is common to apply mixtures of pesticides and other agricultural chemicals, making it challenging to determine cause-and-effect relationships. “The precautionary principle of public health tells us to act when confronting health risks, not to wait for proof,” says Bengal. “Positive proof takes too long,” she emphasizes, advocating for a solution already at hand: organic farming.

CORA is urging Driscoll’s to lead farmers in transitioning away from pesticides towards organic practices, particularly near schools and residential areas (a petition is available on their website for signing). “We’re suggesting they start closest to the perimeter, near the urban boundary and our schools,” states Scow. CORA has published a map showing conventional fields near Watsonville within 1/4 mile of local schools and homes that currently use pesticides; many of these fields are controlled by Driscoll’s and/or affiliated companies.

Most farmers in the Pajaro Valley have contracts with Driscoll’s, meaning they grow exclusively for this company. While they are legally independent, they heavily depend on Driscoll’s distribution network, which controls markets around the world. Currently, approximately 20% of farmland in the Pajaro Valley is free of pesticides and organic, and Driscoll’s, along with REITER-affiliated companies, also operates many organic farms. “There is no doubt they could distribute organic berries if more farmers choose to transition to organic agriculture,” says Scow.

However, farmers are often reluctant to shift to regenerative land practices. Firstly, there is a three-year transition period in the U.S. During this time, farmers must continue to grow berries without pesticides, resulting in lower yields, and Driscoll’s cannot sell these berries at a higher price until they are certified organic. Secondly, organic farming requires more effort, and farmers are already under pressure to feed us all at increasingly low margins.

While farmers are at the heart of this shift, CORA believes they cannot do it alone. Driscoll’s has the power to lead the organic movement, phase out pesticides, and help unlock the support needed to make change possible — starting in urban areas and schools, and growing from there. “Currently, organic fields rotate between organic strawberries and organic vegetables grown by other companies. This is beneficial in organic farming as it helps preserve soil health,” explains Scow.

And he adds, “Let’s emphasize that what Driscoll’s is doing is legal — our local government is prohibited by law from regulating pesticides. The state stripped it of this authority 30 years ago, and we no longer have local jurisdiction. Therefore, we’re in the only position of calling on the management of the company to make a change.”

In December 2022, CORA met with Driscoll’s for the first time, and they had another meeting this year. “In principle, they say they are open to the idea. However, it seems some individuals are standing in the way who don’t want to change,” explains Scow. He and the team at CORA feel that some progress could potentially be made, but it may take a long time. But the health consequences of both acute and chronic exposure to pesticides, especially in children, are devastating. Valerie Bengal, who retired from clinical family medicine in 2023, reflects on her patients’ experiences with serious health issues. She says they will stay with her, always.

The urgency of the situation is also against the business clock. Experts in regenerative agriculture agree that the continued use of banned chemicals degrades topsoil, and it could take decades to restore its health. “It’s an ongoing experiment here, so if nothing changes, we would be able to confirm when the topsoil is completely dead,” says Scow. The power to change is indeed in Driscoll’s hands.