Every day, Nicole Preuss wakes up around half past seven, and gets ready to take one of Valparaiso’s red buses which drive up Quebrada Verde, a hilly street from the waterfront strip. In other parts of the Chilean city, ravines are so steep that funicular railways, staircases, or elevators, built in another era, do the job.

By rights, Valparaíso should be the mecca of urban enthusiasts. The city is built in the form of a natural amphitheater along the Pacific coastline. Its neighborhoods share a common morphology of scaling gullies and ravines towards the higher mountains. To that end, this city is an apotheosis of urbanism.

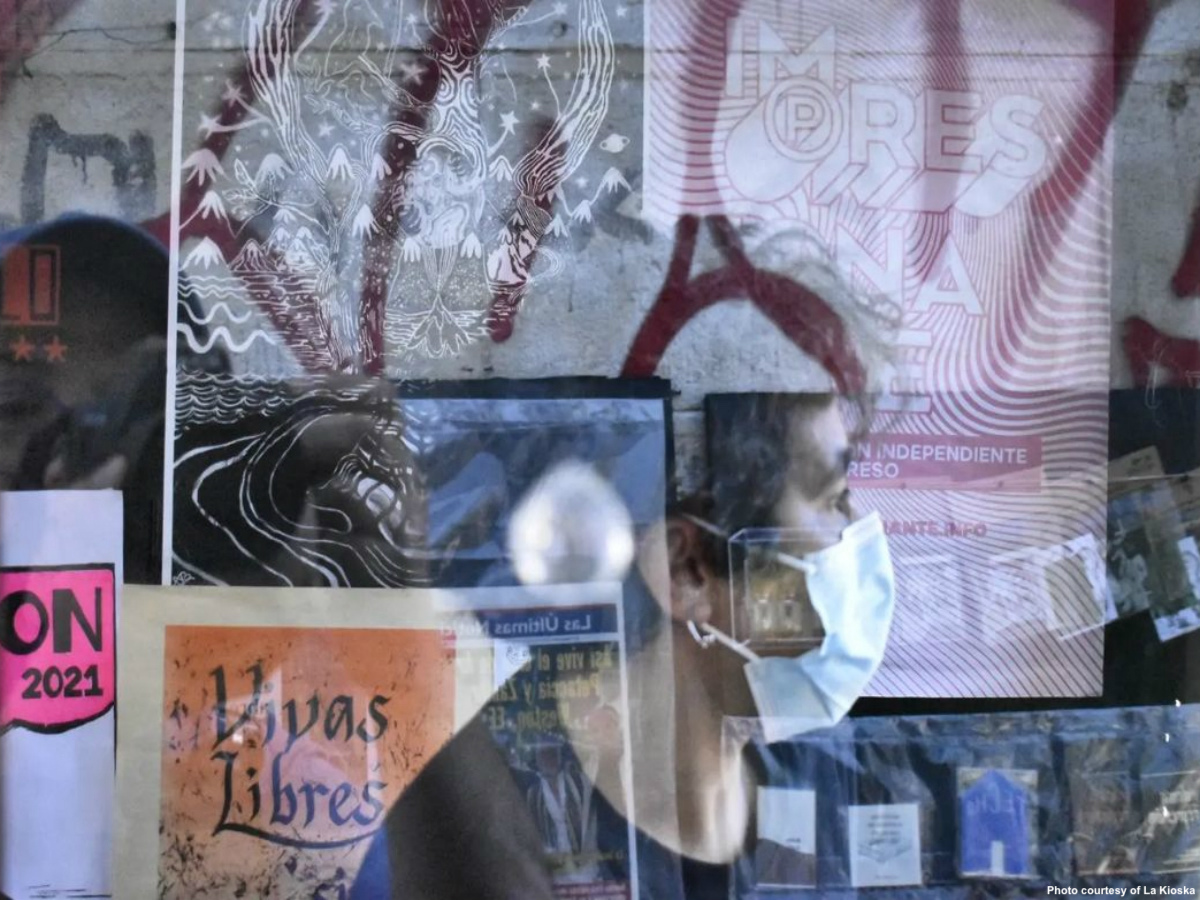

Once at the intersection with Avenida Pacifico Preuss reaches La Kioska, a little quirky kiosk on a narrow sidewalk in the neighborhood of Playa Ancha. Hand-painted shapes in turquoise and pink colors shine on a black background. On the back, a writing says: “Never submissive, always choriza.”

When Preuss raises the metal blinds, La Kioska feels like a forum from which to watch life happen: the garbage truck passes by, the impatient man waits in front of the liquor store and the street starts to get busy with people heading to the market on Thursdays and Sundays. Regular customers stop at the kiosk, the senior residents of the neighborhood stay and talk.

These are small things, the fortuitous social good of urban life. But they are everything, really. Kiosks were places where people stopped on their way to elsewhere, to buy the newspaper, tobacco, a chewing gum or even talk about their day. Despite their charm in the public space, the digital era put the kiosk bonanza in a downward trend of decadence.

Alone in Valparaiso over 200 kiosks have been abandoned, tells me Preuss. She came across the kiosk during the pandemic when she lost her job. Her uncle, the owner holding the license granted by the municipality, couldn’t continue with the business because he was in his eighties and the new Covid-19 law didn’t allow him to step outside the house.

There are many stories and information which are difficult to find elsewhere, concepts which are not addressed.

Together with her partner Majo Puga, an illustrator with a network in the publishing sector, Preuss decided to revitalize the crumbling business. Both were drawn in as much by its sordid side as its cult aura. They called it La Kioska, yielding on a change of its gender (el quiosco is male in Spanish) to send a message of fostering counterculture.

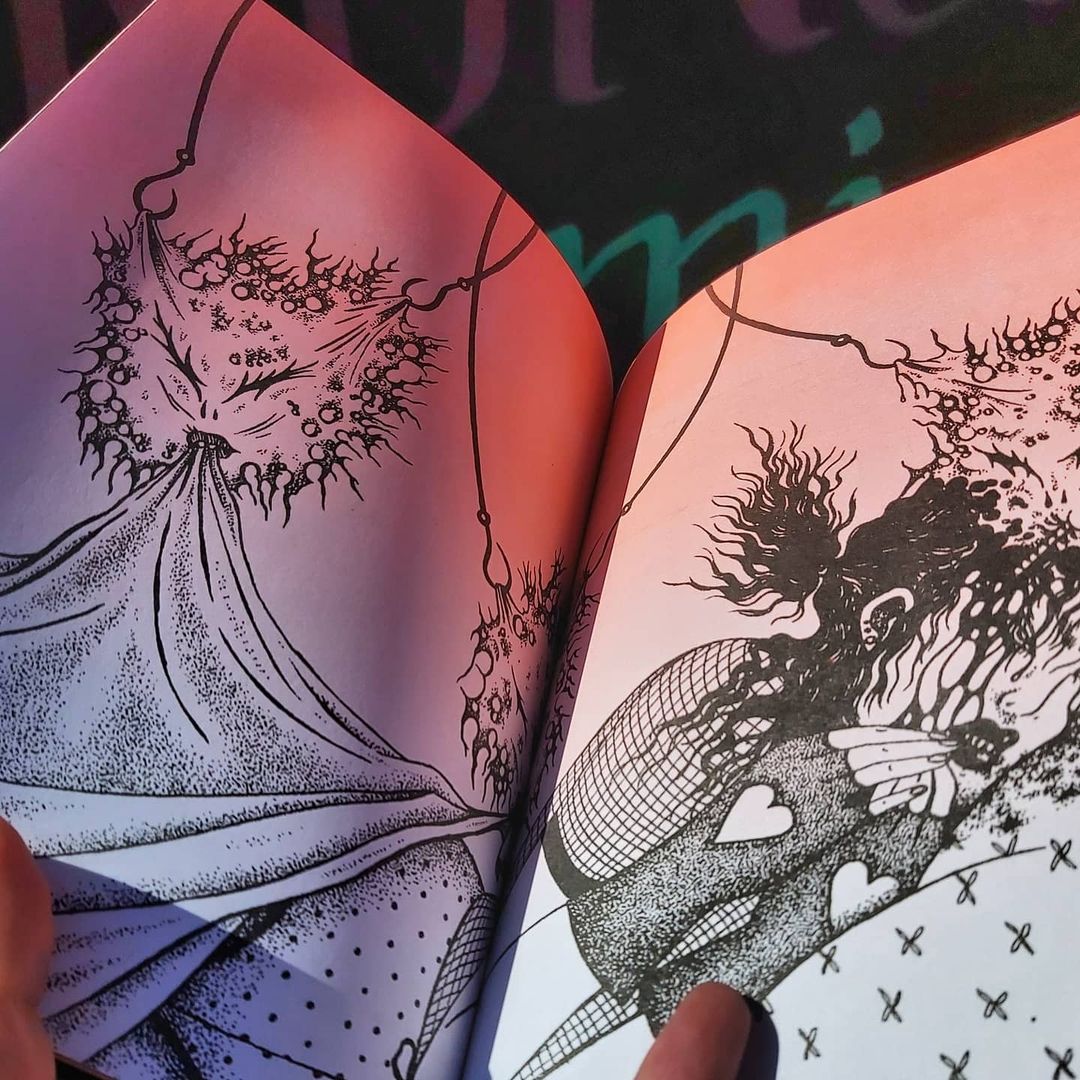

While in other cities kiosks are metamorphosing into cafés with small benches and tables for their clients, La Kioska intends to quench thirst for information. It sells popular newspapers, but it is not the main focus. Primarily, the kiosk offers, as an alternative, publications of smaller print, local editorials from various places around the country and independent material from illustrators and graphic artists such as fanzines signed by authors.

Puga tells me that she is apolitical and is always looking to find alternative answers to our capitalist system. “Easy access to all kinds of information is a powerful tool to promote critical thinking and in areas like the neighborhood of Playa Ancha it is needed. We want to break the monopoly of information,” she says. “There are many stories and information which are difficult to find elsewhere, concepts which are not addressed.”

History has swayed Valparaiso between disarray and the revival of its glorious past, yet “each neighborhood boasts its own cultural microcosm,” says Puga. In the neighborhood of Playa Ancha tradesmen like shoemakers, tailors, and the kiosk, have not been replaced from the public space by the industrial ware. There are many mom-and-pop bookstores, liquor stores, and butcher shops, which close for a lunch break between 12 and 4 pm. Residents shopping around the neighborhood are called by their names.

Preuss and Puga have never stopped selling the regular mainstream newspapers, because “otherwise we would lose the public that interests us most,” they say. Other projects to revitalize kiosks in Valparaiso have tried to focus exclusively on the cultural part but “you can’t survive without keeping the traditional dynamic. But it is important, though, that people know that there are other sources of information. They start to question themselves more and generate filters to not believe everything. That process creates social changes.”

Art in the public space is also an important part of the kiosk’s mission. La Kioska supports artists through the selling of their fanzines, for which there was no other distribution site. In addition, Puga and Preuss work with “situated art” exploring the relationship of people with the exhibitions hosted at La Kioska. Those who see these small but provocative exhibitions displayed in the windows or just outside the kiosk become harder to cow into silence.

“Art is important,” says Puga, “it is an impulse for people to generate autonomy and break the yokes in which our society is enslaved.” In general, the residents of Playa Ancha don’t go to museums or book fairs, reckon Preuss and Puga, therefore “public art is what is needed for people here to form their own opinions.”

Moreover, the work of La Kioska has gone beyond the limits of its neighborhood. Art fairs keep inviting its founders and artists and collectors come from every corner of Valparaiso to see the exhibitions or get that beautiful franzine or independent print which they wouldn’t get anywhere else.

It is remarkable the advances in Chilean art. Since 2016 many creatives from Chile are tiptoeing into global cultural recognition and including the participation in the Venice Architecture Biennale, among others. But Puga seems not to be impressed by that, and says, the Venice Biennale doesn’t say much to the people in the neighborhood of Playa Ancha, they just care about having to eat. “Art has become very elitist, culture is expensive and art is not available to everyone,” she laments.

While the City Council has turned a blind eye over what the license allows a newspaper kiosk to do, La Kioska has expanded its role to democratize information and art in the public space and help people understand the world around them. “And, how is people’s reaction to La Kioska?” I ask. “At the beginning the neighbors found it difficult to understand what we were up to, but slowly they got used to exhibitions and publications that represent other narratives and the impact is becoming visible.” Apparently, the search for truth has sparked people’s interest and curiosity for something that could intrigue them.

Two weeks before our conversation, a car had accidentally crashed into La Kioska, tells me Preuss. She wants me to understand, at this point, how people have become intertwined with the kiosk: “Our regular customers have reached out with their support because they want us to open again soon.” And, she adds: “We are waiting for our Municipality of Valparaíso to authorize us to change our structure, in order to install electricity and thus improve our services and opening hours.”

I wonder if there is something with this city, one-time home to poet Pablo Neruda, and where the first public library of the country and the world’s oldest Spanish-language newspaper is still in print, having been founded more than a hundred years ago.

Without hiding my excitement, I tell Puga and Preuss how unique their work is of shifting the purpose of the kiosk in the public space to reframe the neighborhood with the written word. And Puga, citing the Chilean writer Gonzalo Rojas, says: “It is not enough to want it, you have to deserve it.”