When Glenda Obermuller arrives at our virtual space, one is immediately struck by her jet-black curly tresses that reach well beyond her shoulders. Wearing a black cotton tee with the words “Melanin Power” written across the chest, and black thick-rimmed glasses, her image harkens across time to the Black Power activists of the 20th century and the Black Lives Matter activists of the 21st. Obermuller is the co-founder and curator of the Theodor Wonja Michael Library, the first Black library in Cologne, Germany, and the second in the country.

The two-room library — housing over 6,000 books written by writers from Africa and its diaspora — has become a haven of respite, discovery, and reflection for the people of Cologne and its surrounding communities. But Obermuller will tell you that a library centering on Black literature is not what she expected when she arrived in Germany in 2003.

“I was married,” she chuckles, to a German man. They both relocated to Germany with the expectation that one day they’d return to Guyana, but then they divorced. It was around that time that Barack Obama was becoming an international sensation, having visited Berlin, Germany in the summer of 2008. The infectious hope and enthusiasm he exuded prompted her to return to school to attain fluency in the German language, and matriculate into the University of Cologne to become a special education teacher. Neither the fact that she was a single mother of an autistic child, nor that she was 32 at the time dissuaded her. “I believe in myself and what I do because my intentions are pure,” she says, pushing her glasses up her nose.

Throughout her studies, Obermuller maintained her plan to return to Guyana with her son, to be surrounded by her large family there. She had read a UN study in the early days of her arrival that became a compass for her. According to the study, she says, after living in a new place for 20 years, an immigrants’ desire to return home generally disappears and they focus their energies on staying in their new country. But as her own twenty-year mark approached, she felt the growing urgency to return home.

***

Obermuller was born and raised along the Pomeroon River in Essequibo, Guyana. Growing up in the fertile soil, sweetwater grasses, and rainforest was a feast for the senses, she recalls. Her father owned and cultivated a farm, until his untimely death when she was 14. “It was my mother, then, who took care of us and raised us.” Though they have little means, she says, her family didn’t lack for anything. “We had clean clothes, organic food, and were never sick.”

Her parents, Harry and Maria Obermuller, were staunch proponents of education. Her father was of African descent who had a white German grandfather, and her mother an indigenous woman of Arawak descent. Obermuller’s great-grandfather arrived in Guyana in the 1900s from the Black Forest with a wave of German migrants seeking wealth as plantation owners and slave traders. “Germany was not foreign to us. We knew our history.” Yet, despite the horrific history of her ancestor’s activities, Obermuller tells me that they were told about their German roots as if it was something to be proud of.

The eighth of 12 children, Obermuller was a precocious child, having read the entire Bible at the age of 10. “It was easy because it read like a story book,” she chuckles. She could be found on the branch of one of the mango trees on her family’s land reading the Bible, a newspaper, a novel, or any other material she could get her hands on. Her mother was very religious, with a quiet spirit, that exuded tenderness and care. “I remember my mother always reading,” an influence that remains. But it was her father’s character in the face of adversity that made the greatest impression on her.

Harry Obermuller was a well-read, masterful orator and people-person, despite having a limited formal education. (He completed primary school.) A grassroots politician and member of the United Republican Party of Guyana (URP), his goal was to ensure social justice and free and fair elections during the new-independence era of Guyana. “He was a principled man, my father. You always knew where you stood with him.”

She describes him as a visionary, direct in his telling, compassionate in his motives. But he had his demons, and alcoholism was how he coped with the violences resulting from centuries of abuse of his people through the slave trade, colonialism, imperialism, and neo-liberalism. “He had big plans for [Guyana].” Sadly, one year after the first “free and fair elections” since Guyana’s independence were held, he died. He had been sober for a year, and was in the middle of developing a large factory for drying fruits to export and support the local economy.

“I remember one day, just before the elections in 1992, the President of Guyana — a member of the ruling PNC [People’s National Congress] party — came to the market place where we lived to give a speech.” In those days, all the schools would halt studies and march students to the market to give audience to the President. “Mostly for propaganda,” she added. As she stood with her friends in the broiling sun listening to the President speak, she recognized the man approaching the stage. It was her father. Mortified, she watched as the guards began making their way towards him. Loud enough for everyone to hear, he said, “I want to ask the President a question.” The president stopped his speech and responded, “Mr. Obermuller would like to ask a question.” She was shocked that the president knew her father’s name. “This mattered so much to me,” she recalls.

The question he asked has been about “what happened to some millions of dollars,” but she remembers the president “shooing” her father off the stage and her classmates teasing her about it for weeks after. But this did not bother her — she took it as a moment of pride and her father’s bravery.

In 2015, Obermuller and her son settled in the town of Cologne, known for its liberalism and progressiveness. “But this is mostly in the external sense,” she states. Despite being the first city to ban usage of the N-word (twenty cities in Germany have since followed), racism and discrimination persist. Museums still carry stolen artifacts from the communities in Africa ravaged before and during the colonial era. Blackface still appears at the world-famous Carnival in Cologne, despite communities saying how hurtful the act is. “But I remain cautiously optimistic because of [Cologne’s] efforts.” She’s speaking of Cologne’s recent commitment to addressing its colonial past by developing a 10-person committee to provide the city recommendations on how to improve. Seven of the ten committee members identify as “Black,” and she is one of them.

***

Theodor Wonja Michael, for whom the Library was named, was born in Germany, and lived in the city of Cologne later in his life until his death in October 2019 – three years after Obermuller began organizing community events in the city. He, too, despite being born and raised in Germany to a Cameroonian (Black) father and German (white) mother, faced racism as a child, even being forcibly recruited to be in pro-Nazi propaganda during World War II. After the war, he went on to be an activist for equality in Germany. Two hundred books from his estate became the pillar for what would become the Theodor Wonja Michael Library.

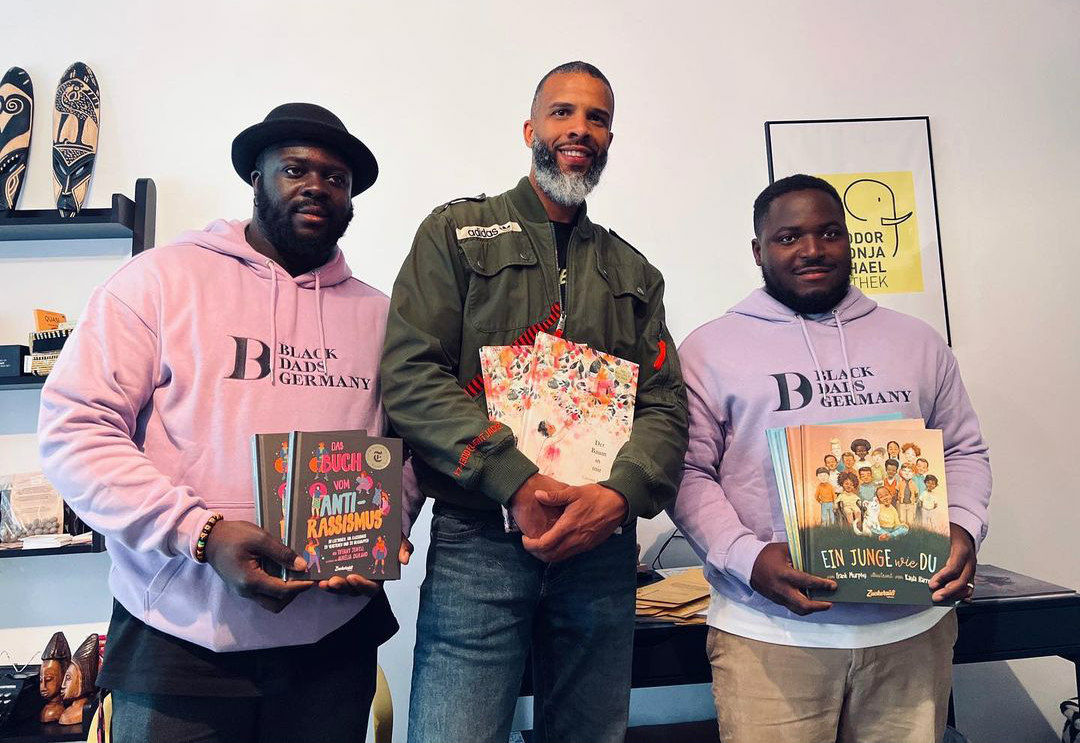

“Despite the work I was doing, I was making plans to leave.” She was approaching that 20-year mark she’d read about and grew antsy about what it would mean to stay. Then the COVID-19 pandemic came; she and her son could not leave. As her son’s condition deteriorated, she decided to put those dreams on hold. Two months into lockdown, a monstrous killing occurred: an unarmed Black man in the US named George Floyd was murdered by a police officer and broadcast on screens for the world to see. Germany erupted in protests, including two in Cologne. As she and one of the organizers looked out at the sea of thousands who had come to protest along the banks of the Rhine River, she saw an opportunity to bring people together. “[We wanted] to reflect upon and talk about what happened, what we want to see happen,” she remembered.

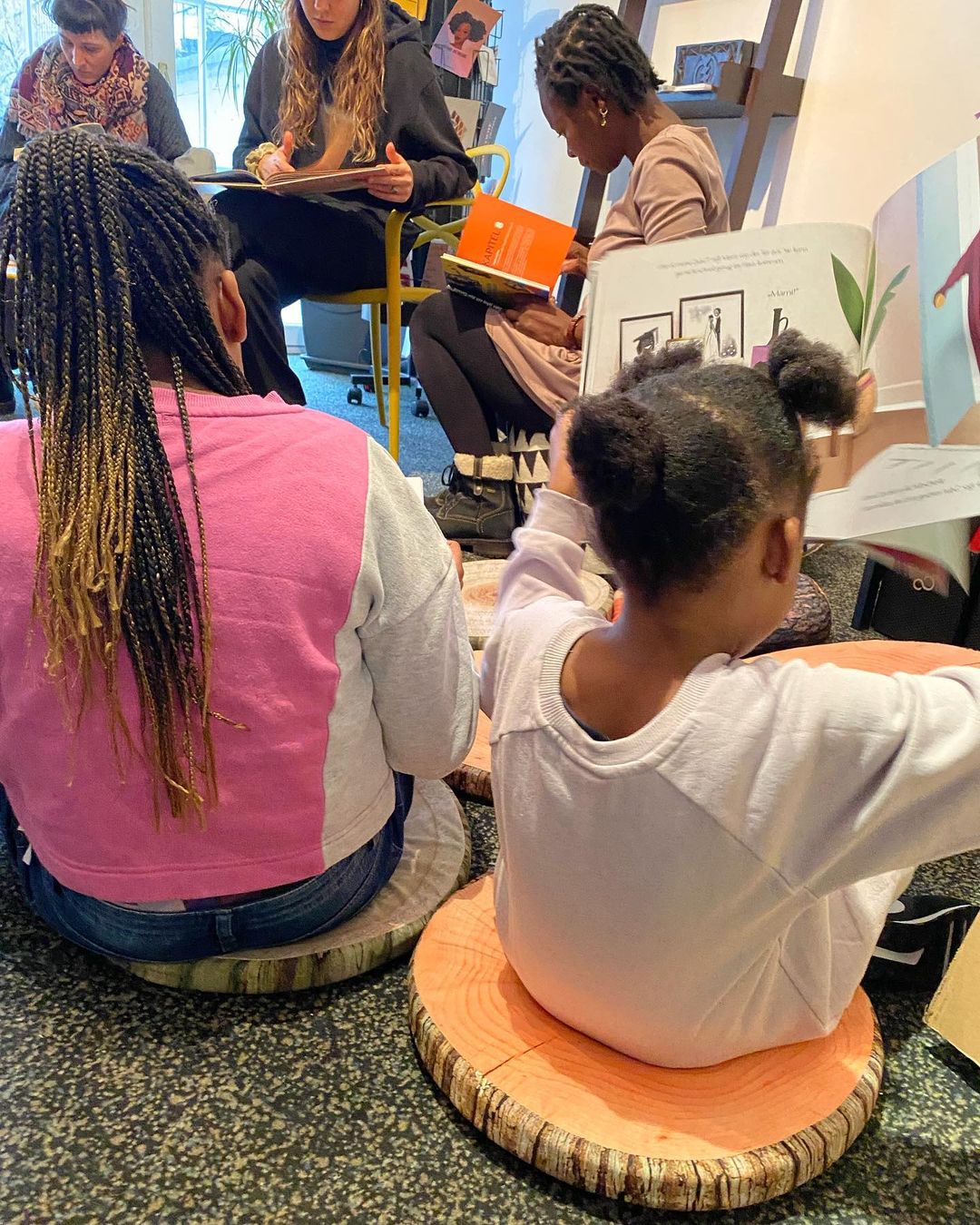

Shortly after that, they held an event at the park for Black people to brainstorm in a safe-space. It was then that someone wrote on a list “a Black library for us,” following the example of the Black-led organization in Berlin called “Each One, Teach One”. It wasn’t the first time someone had mentioned to her about starting a library centering Blacks in Cologne. In February of 2020 at a Black History Month event she had organized in Cologne, a friend of hers also encouraged her to start one.

***

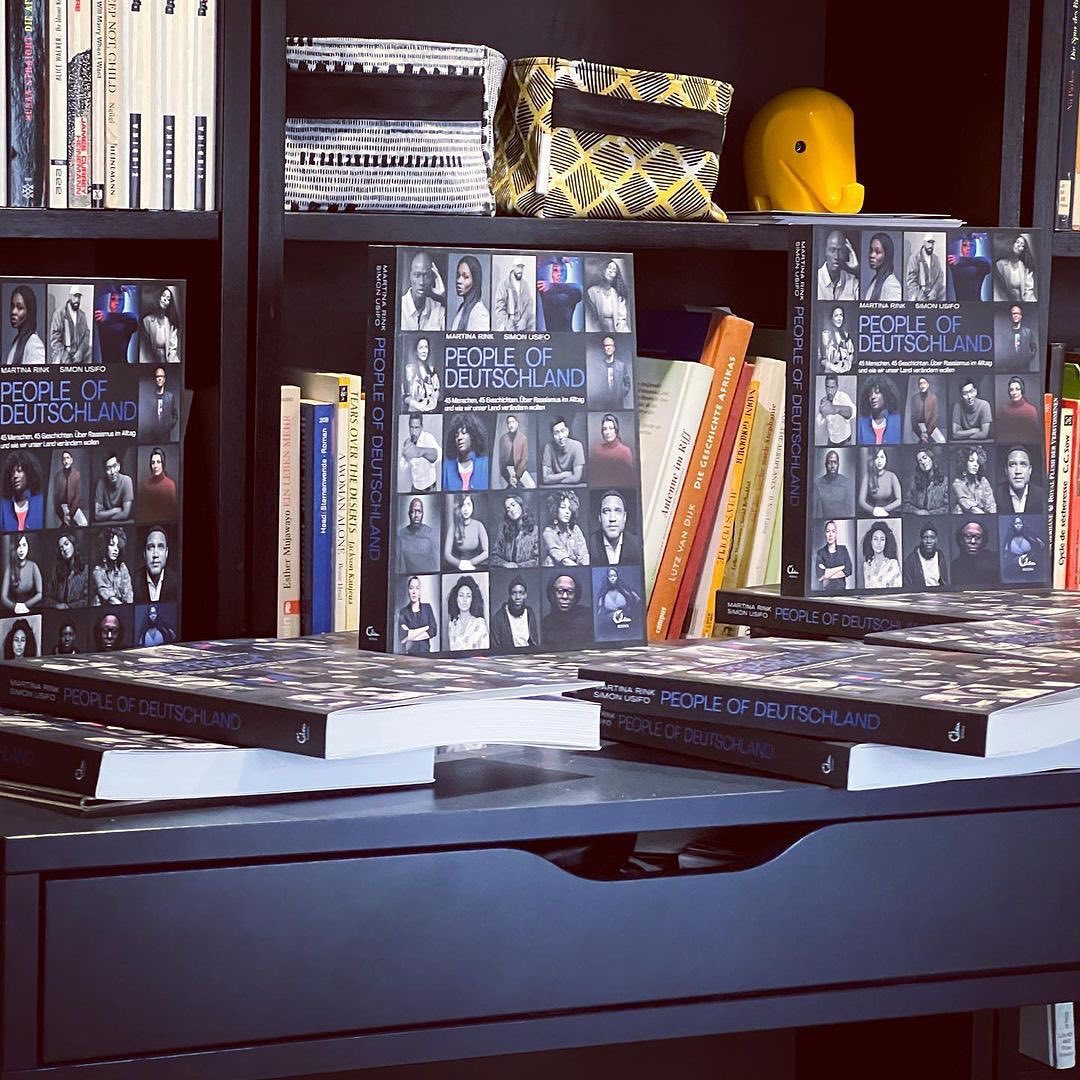

Two years and one thousand books later, the Theodor Wonja Michael library opened. Now, entering its third year, and largely operating on the donations and generosity of supporters, the Library contains 6,000 volumes. Most of the authors are of African descent, including many Black Germans. Most of the books are written in German and English. Less than 1% are written in African languages, mostly Swahili and Lingala. The hope is to have the Library filled with books written by Africans around the globe, in their languages. The Library’s primary goal, according to its website, is to “convey an unprejudiced and decolonial image of Africa and people of African origin…to not reproduce racism.”

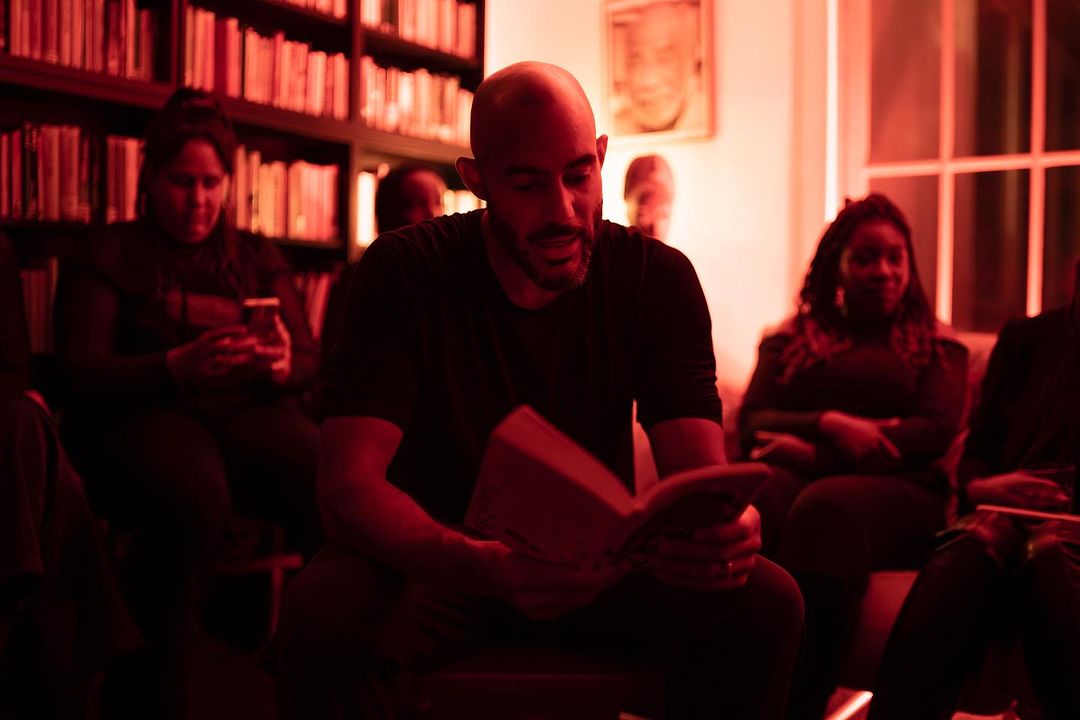

Their efforts are not lost on those who enter the space. She recounts the story of a man from Bavaria who visited the Library. “When he entered,” she said, “he told me, ‘this is a place where I feel compelled to be silent. It is a holy space, like a temple.’” Others have remarked that the Library is a place of safety, a place to be still and rest. The parallel story she read as a child, of Moses at the burning bush, comes to mind. “When he hears the voice of God say, “‘Remove your sandals for you are standing on holy ground’, it’s like that.” People enter the space as if they have finally come home.

The indigenous people of Guyana, the only Anglophone country in South America, called their land guiana meaning “the land of many waters.” “I grew up not even 50 feet from the water,” she says. “[Water] is a place I find peace; it is the place I always return to.” That the dire consequences of Guyana’s Dutch and English colonial past persists today is not lost on Obermuller. But it remains home. And it is the water’s properties of flow that come into her work as an activist. It’s how she avoids burnout, by working in flow, like water. While the river and its landscape are not the same in Cologne, Obermuller finds herself drawn to the natural world in her new city. “But the sauna,” she emphasizes, “is my respite.”

Every month since 2019, she leads a group of Black women to the sauna for a retreat. “Without wellness, I wouldn’t be able to be a caretaker for my son or do the work I do.” This helps as she notes that she has little patience for nonsense when it comes to social justice. “I will make friends with everyone and win them over to our side,” she laughs. She is determined. Much like her father. “I want my little girl self and my son to be proud of me. Plus, my ancestors were creative. They had to find ways to survive. I will, too.”

Obermuller did not set out to be an activist, to live in Germany beyond a few years, or become the face of activism in Cologne. Still, the kind of life she has forged and the work she is doing at the Library to make Cologne, Germany (and the world) a more equitable, safe space for everyone, especially Black peoples, gives her a meaningful reason to stay.