On a sunny day in London two people wavered in their answers when asked how a building behind them made them feel. Another Londoner brooked no hesitation. “It just looks like another boring building in London compared with other buildings with a lot of history.” And then he said, “A lot of stuff in London is becoming quite square and rectangular. It doesn’t get you any creativity or love for architecture.”

What some might see as the awkward moment of a random Londoner dumbing down the architecture profession, has in fact some based evidence. Already reputed psychologists and neuroscientists have empirically demonstrated that our built environment profoundly impacts our wellbeing and mental health.

Some years ago, ‘undercover’ volunteers acting as lost tourists approached pedestrians asking, “Can I borrow your phone? Can you give me directions?” Pedestrians who were asked in front of an active façade were seven times more likely to let the ‘tourist’ use their phone, and four times more likely to offer to lead them to their destination, as opposed to being asked in front of a shiny hostile building in the same neighborhood. This urban experiment conducted by Happy Cities in Seattle contributed to prove that buildings also influence our relationship to each other.

But there is so much more that the public could reveal to the people “who didn’t really care enough or didn’t understand the impact that buildings have on all our lives.” Last month Thomas Heatherwick, founder of award-winning British design and architecture firm Heatherwick Studio, launched the 10-year global campaign ‘Humanise’ to give a voice to everyone. That includes a call to submit a photograph of that building “you have to walk past every day and you think it is boring or depressing.” Your input contributes to a new “Boring Building Index”.

The campaign’s goal is to engage the public in a conversation about health issues caused by boring buildings and inspire a movement to demand better, more joyful and human cities through the design of buildings.

The first time I listened to Heatherwick was during a talk titled Human City at the WRLDCTY conference in New York over a year ago. He hoped that a more human-centered design would bring some cheer to boringness in the way we build cities devoid of character and meaning. Since then he has been much more explicit about the transformative potential of buildings to inspire and improve urban dwellers’ wellbeing.

***

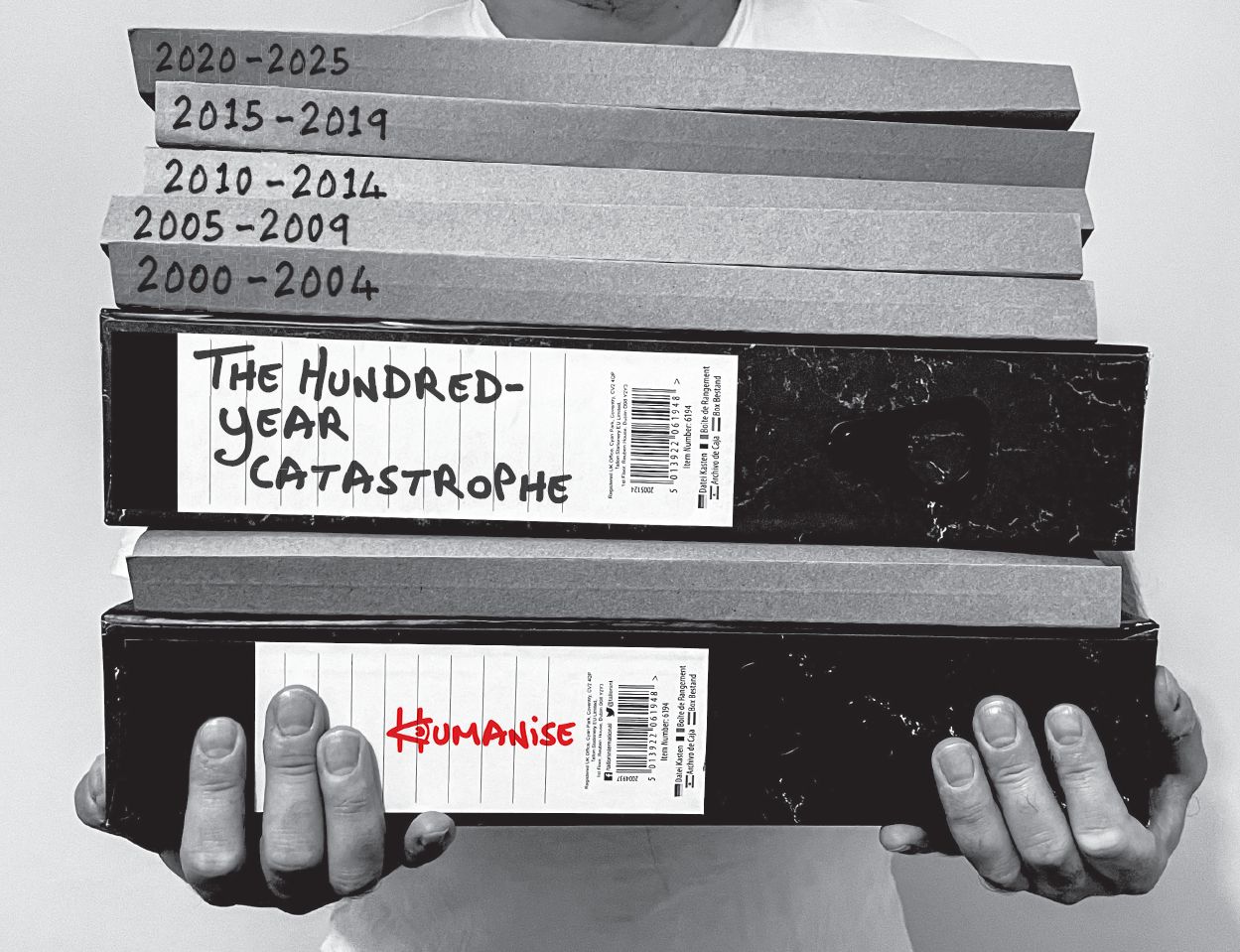

Heatherwick uses the history of the architecture profession of the last 100 years to inspire a structural revolution, one that deployed a serious artillery of research and the publication of a new book called Humanise – A Maker’s Guide to Designing Our Cities – all intended to involve the public with the unraveling mysteries of our emotional response to architecture.

For millennia even the humblest building had interest, delight, materiality and complexity but he speaks of the architecture of the last century as a “hundred year catastrophe”. After World War II, architects were building fast, cheap and convinced themselves that straight lines are good. It was almost the perfect storm that put the construction of buildings in an almost unique situation in history that kept us stuck in the habit of producing boring buildings. “One reason Modernism endures today is because it’s perfectly compatible with cheapness,” argues Heatherwick in his book.

Heatherwick’s assertions have already spilled much ink about his book and the movement, not always positive, some try to find references in some of Heatherwick’s contested designs and buildings. But the campaign is not about Heatherwick’s work. In fact, ‘Humanise’ explicitly doesn’t use the word beauty, tells me Matt Bell, Communications Director at Heatherwick Studio. “It is not about traditional versus modernity either, but rather boring versus interesting.” While “It is hard to declare a building to be beautiful or ugly as a matter of fact,” there is less disagreement about boringness.

It’s safe to say that nobody wants to see boring buildings. Heatherwick has just opened a Pandora’s box about architecture, our brains and our hearts, in other words, the connection between aesthetics and neurology. Boring buildings and low-quality built environments cause spikes in cortisol levels, increased loneliness, and reduced psychological restoration. They deprived the brain of information – too flat, too monotonous, too homogeneous – and when this happens, say scientists, the brain “panics.”

The impact of bad design on mental health is as significant as on the environment, the relationship between livability and sustainability goes almost hand in hand. The construction and building materials industry is responsible for 11% of annual global greenhouse emissions, that is 5 times more than the amount of carbon emissions of the entire aviation industry. “The demolition rates for a lot of new development are horrific,” says Bell. In the UK the average lifespan of a commercial building is just over 42 years, in Tokyo it is only 30, in the US an area which is half of Washington DC is demolished every year. To put it bluntly, “nobody cares,” bristles Bell.

“The movement we want to create is not about how to change policies, or to get governments to regulate all, it is about trying to shift the mindset. So it is a mindset movement, really,” he says. One that changes the public discourse, ordinary urban dwellers as well as professionals working in the industry. That Bell leads the ‘Humanise’ campaign is not accidental. He has spent a lot of time working in urban regeneration and housing project schemes as a community engagement specialist, all his background was in the third sector. “I think the way we make our cities better is to get the physical and the social to connect,” he says.

“When you look at when change happens in the world, and how it happens, I think a lot of campaigners instinctively reach for the government to take charge and impose policies, because that would solve everything.” But we agree that it almost never does. If there is not a change in the mindset, people find a way to go around rules and policies. And Bell adds, “This is why it is so important to get a public conversation, trying to figure out what is acceptable in our cities and reset the consensus, if you like, in the same way as it happens with things like people’s perception around urban pollution or plastics.” It starts with a change in society, not with a change in government, who eventually will concede that things are moving forward to inspire new policies.

But it takes a long time to get “a big societal reset,” the main reason for a 10-years long campaign. One of the interesting examples to look back at is the urban activism of Jane Jacobs in the 60s, or Jan Gehl’s approach on pedestrian behavior and street life or when scientists began talking about climate change. “People pick up on these ideas many years later,” says Bell.

Once the conversation about the impact of boring buildings is in the public ethos, Bell thinks that there is a chance to inspire and encourage the progressive elements of the real estate world that will see where the world is going, and will be followed by all the people who design, commission and approve what gets built.

Thus the ‘Humanise’ campaign wants to be a coalition, inviting partners on board and looking out to network with professionals, community organizations, individual cities, and companies of different sizes. “In particular, connecting people in the world of design and activism is quite rare, both are very creative, but they hardly speak to each other. If we could connect them, that’s when we could do extraordinary things, and hopefully could take us into a much more inspired, encouraging and life affirming discussion,” says Bell.

I asked him if ‘Humanise’ had considered that, by making buildings more interesting and attractive in, for instance, impoverished communities, it could end up pricing out locals. “The issue of displacement is not the focus of the ‘Humanise’ campaign,” however he adds, “if developers would focus on interesting, not beautiful, buildings they would probably conclude that what’s interesting is probably already there. They would consider keeping it because it has attracted people to that place for the last 20 or 30 years.” Bell, who has been on both sides, strongly encourages developers and local community leaders to meaningfully listen to each other.

I told Bell that I noticed that there is a demographic group that feels particularly challenged by their movement. “Yes, all the negative reviews we have got are by white men over 50, while all the good ones are made by a bunch of diverse people,” he reckons with a smile. And he alluded to one architecture critic in particular that accused them of being too simplistic, a compliment for them, but seen as negative by him. This is such an important point. The campaign intends to be as understandable and accessible to everyone precisely to involve all kinds of people in the movement, that of course will diversify what gets built. As a consequence, it will better reflect the diversity of our cities, “which currently get built by a very small group of people, really,” he says.

***

Bell can see why architects struggle with a simple juxtaposition of boring versus interesting buildings. “Architects in the UK spend about one hundred thousand pounds on seven years of education to qualify and they understand the complexity of these issues,” he tells me. But an interesting study in the UK by Dr. David Halpern in the late 90s found evidence that the longer architects study, the more their views diverge from what the public likes.

‘Humanise’ challenges a lot of mainstream thinking in architectural education and that “has ruffled a few feathers.” But hopefully the campaign will get architecture critics to talk about the impact buildings have on the passers-by and how they make the public feel. Boring buildings may be everybody’s fault but “architects are the ones that generate ideas and the drawings. They are the intellectual engine behind the design of our cities. But you can’t enjoy that role and then say the outcome isn’t your responsibility. We want the professionals to step up and embrace ‘Humanise’. It’s in their interest.”

Bell tells me that they are also deeply troubled with how much conformity there is in the education of young people instead of letting them be creative, because they don’t want to “be the weird person who gets to sit in the corner.” Heatherwick’s studio is also about to launch an education program for eleven to fourteen years old kids to try to get them to think about creativity and apply it to buildings in cities.

I wonder if the movement could spread in the industry without sacrificing part of the profit over “interesting buildings”, but Bell argues with what they call the ‘human premium.’ Usually the private developer takes the short term profit and the public sector is left with the long term cost. Bell explains that most new developments have some value or contribution, but very often, the building deteriorates and gets worse quickly. At that point the developer is gone, thus it is the public sector, the taxpayer, who is left with the social problem and the cost of remediation due to bad design.

The ‘human premium’ in a way is trying to open the conversation and be quite explicit about why the industry wants to be clear about their profit, at the beginning, while the cost is not quite through. City governments are often too weak in terms of capacity and confidence to demand from developers what is reasonable for buildings, to be human and interesting and to have a thousand years mindset of existence that will protect the taxpayer for the medium and long term.

Is the boring design of buildings also a reflection of the state of our cities? I point out to Bell. Perhaps by rethinking and reimagining them “as fundamentally life enhancing, emotional experiences” they would in a way create the conditions to indirectly address some other urban issues. Like the return of craftsmanship to cities (Heatherwick says architecture “is the work of human hands”) or make cities more inclusive. “We are not trying to solve all the problems of every city, and ‘Humanise’ is not about the public ground,” insists Bell, “but we are certainly trying to do something different.”

By focusing on the outside of buildings and on a collaborative and open public conversation, they hope, that would ultimately touch on other social issues in cities. That is why it is not an imposing campaign because the outcome can be different in every city, even neighborhood. The solution is going to be bespoke for everyone.

Finally I ask Bell if Heatherwick is not afraid of retaliation by being so explicit about the architecture profession. “He does care, on a personal level and professional level,” and for sure it is going to be a bit bumpy but somebody has to do it. “It requires a degree of bravery to challenge and say what needs to be said.”