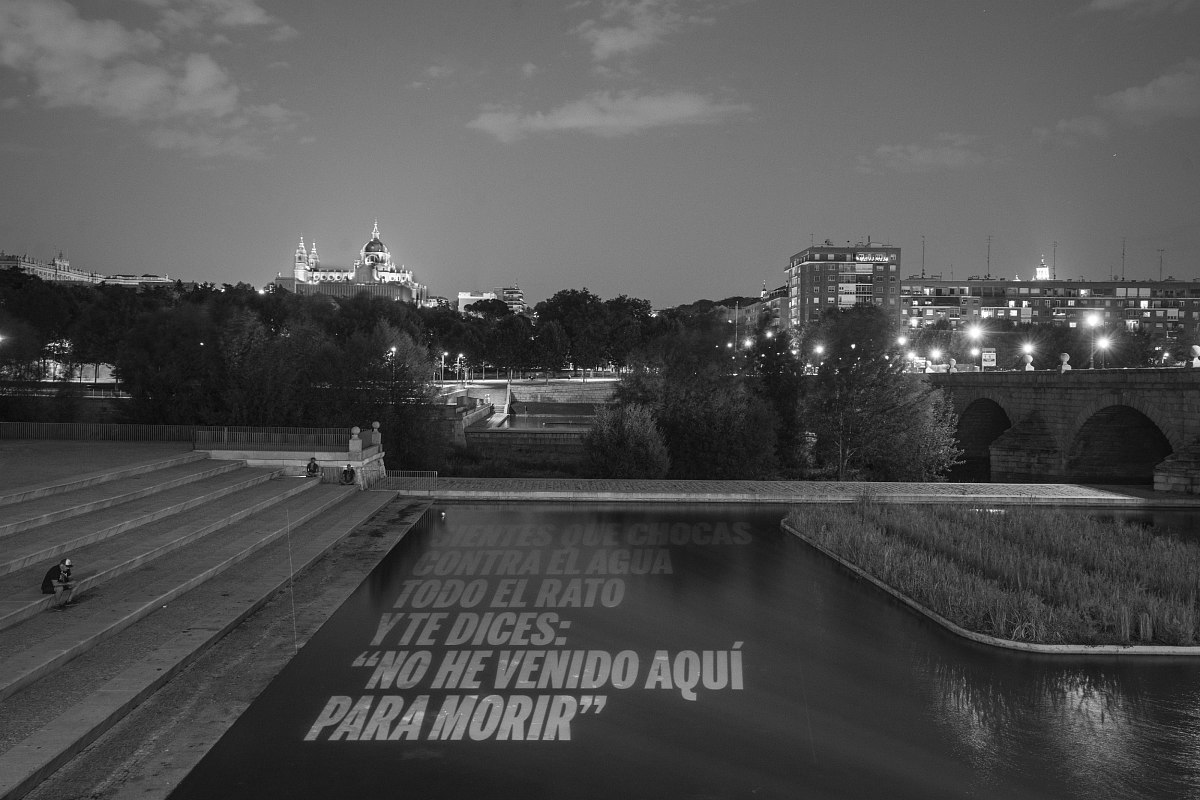

On a hot night last summer, the official building of the Ministry of Labor in Madrid shows a sort of heated facade: “I am not a parasite, I work and contribute. Why should I feel inferior?” Two hours later, another remark emerged from a pond in the park: “You feel like you’re hitting the water all the time and you say to yourself: I didn’t come here to die.”

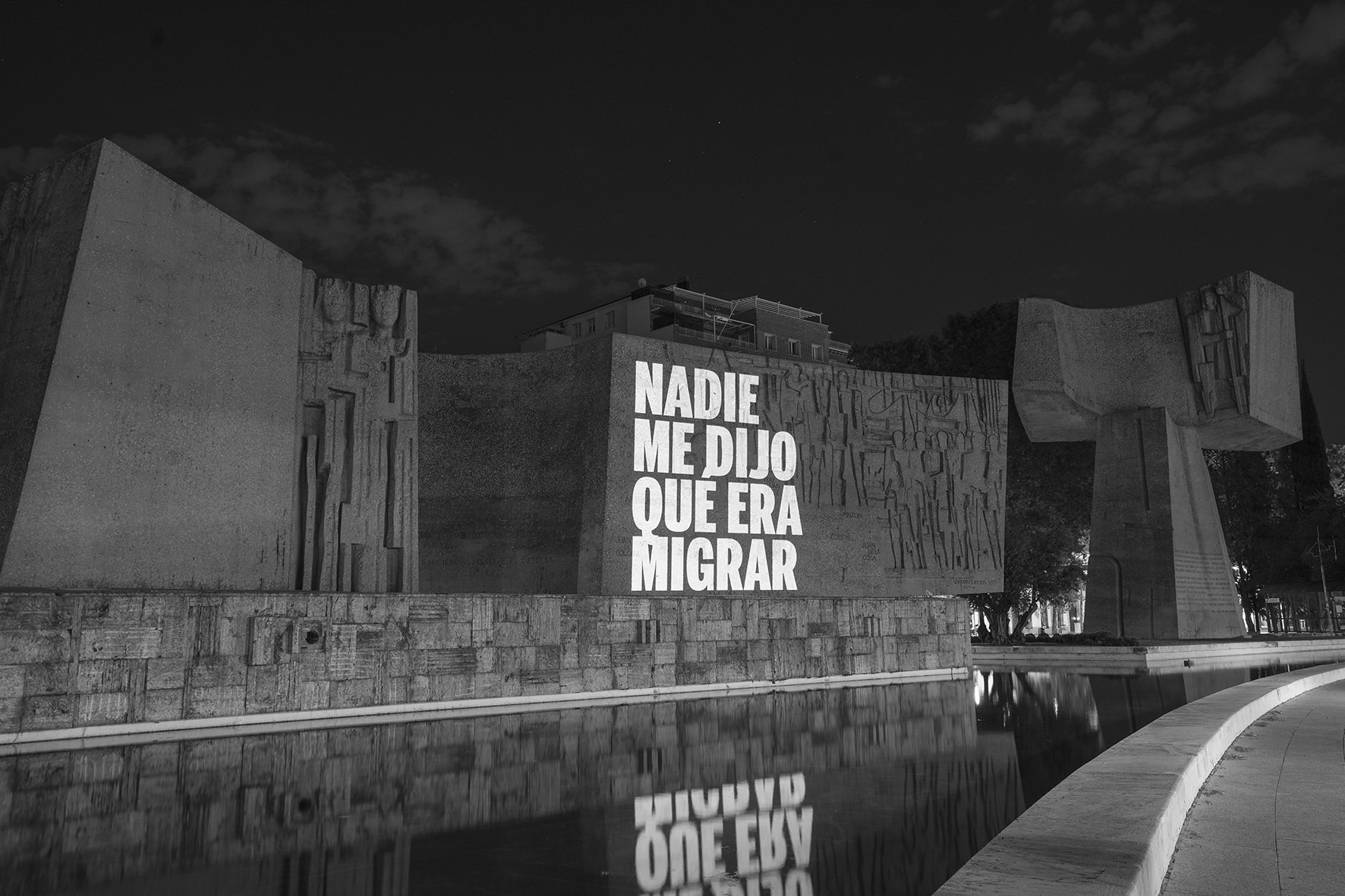

In an act of communication guerrilla, or artistic activism, Jo Muñoz and Diego Peris, armed with a big projector and a camera, pull off a series of projections throughout the city, in collaboration with the artist Martin Flugelman. Everything happened so fast that nobody noticed that they didn’t have any permits from building owners or the local government.

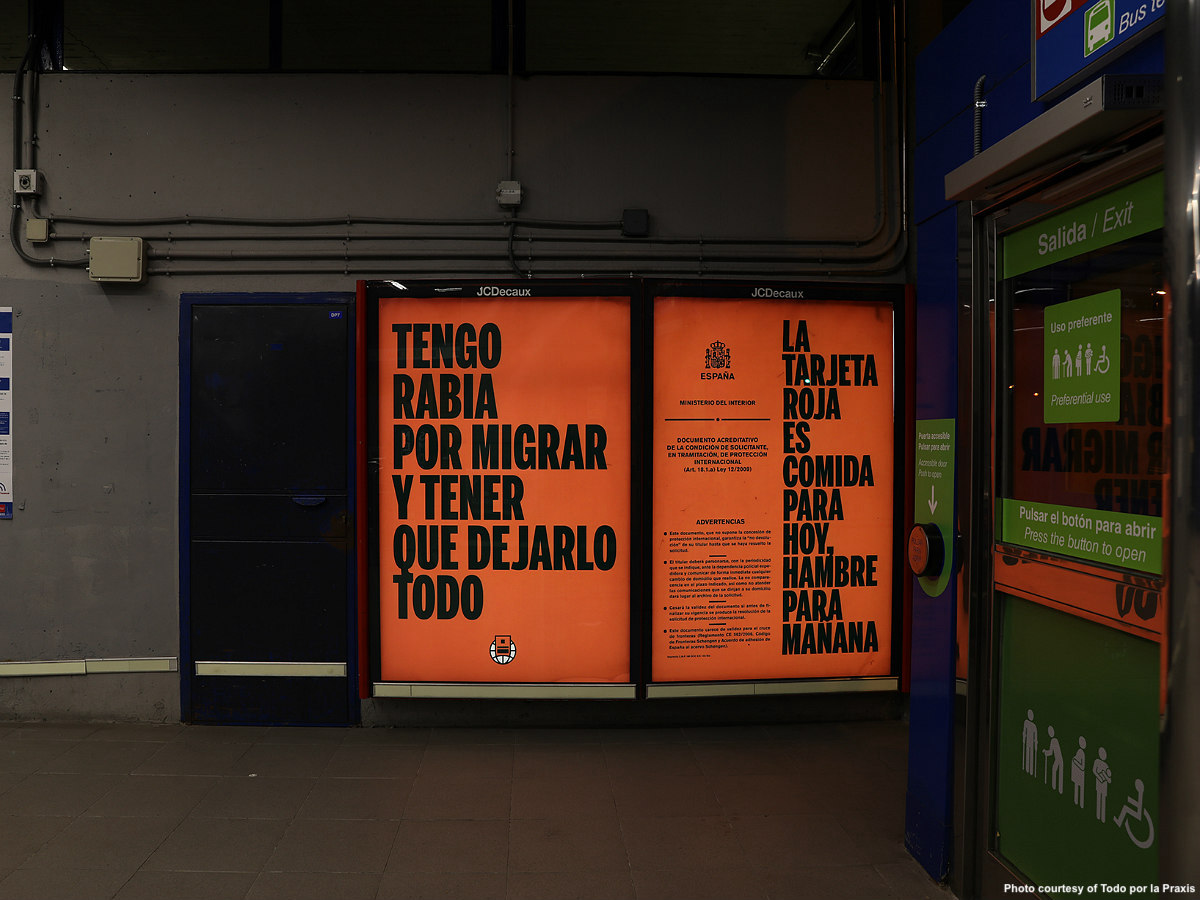

In addition to this collection of ephemeral projections, add-like billboards with similar remarks are displayed around the city. All interventions put together, ultimately illuminate the viewer with their intention. Perhaps through provocation, this act of citizen activism aims at amplifying the migrant voices and tries to generate a reaction from all Madrileños.

Everything is well thought-through. None of the choices of these two long-time citizen activists in Madrid are gratuitous. For instance, the light projection in the water, which speaks of the migrant experience of crossing the Mediterranean sea and everything that implies after surviving it, shows The Royal Palace of Madrid and the Almudena Cathedral in the background. Both buildings were erected during periods of colonialist aspirations. Centuries later the consequences of history are as perceptible as ever.

It became clear to us how many migrant stories were very deep inside people, not known to anyone.

A billboard inside the Aluche metro station reads “I am angry about migrating and having to leave everything behind”. This metro stop is just a few steps from the CIE (Foreigner Internment Center) and the Police Station where all migrants must process their papers in Madrid. Another billboard is near the Madrid Assembly because, in the words of one of the voices participating in this project, “politicians should see it every time they pass by.”

“Surely this intervention does imply adopting a particular ideological stance but it doesn’t pretend to be propagandist, although we adopt, on purpose, the aesthetics of propaganda,” explains Muñoz. Big black capitals on red backgrounds for the billboards are not a random choice. The artist noaz, in collaboration with Muñoz and Peris, was inspired by the design of the red card, a document unknown to many Spaniards, which asylum seekers get in Spain for six months but that implies many limits on freedom.

However, most importantly Muñoz and Peris accrued stories hidden behind real people and put their words on the displays. In November 2021, the La Caixa Foundation approved a grant within its Art for Change program that allowed them to launch the initiative Talking Pot, Common Spoon. How to cook other stories. This initiative facilitated the exchange of anecdotes and experiences among people, who have been granted asylum in Spain. “And what better way to create a community of trust than by cooking!” says Muñoz.

For six weeks Muñoz and Peris have been cooking with a group of people, Lisbeth Sotillo Villarreal (VEN), Consuelo Mayo Gómez (GNQ), Alvine Liliane Nkoundou Sandje (CMR), Lionel Zukam Ouambo (CMR) and Bryan Ladino Múnera (COL), and listen to their different experiences in crossing borders to be a refugee in another country. They are workers from the insertion company CAUSA and are cooks for the canteens of the CEAR (Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid) centres in Madrid.

“The kitchen and the recipes became an excuse that allowed us to collectively think about what these words really mean and the individual and collective identities of each one of us,” says Muñoz. These stories, gathered in sentences, come from a long process of sharing meals, discussing, questioning privileges and debating about migration, the notion of asylum and refugee.

“It became clear to us how many migrant stories were very deep inside people, not known to anyone,” and Muñoz continues explaining that either fleeing due to threats by drug trafficking cartels or escaping the rampant ethnic violence in their communities. “Their stories allowed us to reflect on the scar left by trauma and the grief that comes with migration.”

From there Muñoz and Peris, together with the art historian Fidel Villa Barquín, selected those phrases and concepts that would be protagonists of the visual part of their work. “In them we find five different voices through which to rethink the meaning of migration. We saw the need to create other narratives in the city because migration is still not well understood, especially at a time when the far-right is getting more support in Spain,” says Muñoz.

Not everyone is happy to be in Spain, not all are well, they have to leave their homes and now they have to face social stigmatisation: “We are not from here, we are not from there. The wound will last a lifetime,” reads another of the remarks on billboards.

Muñoz and Peris practise an unconventional dual approach to “curate” the city. She is a visual artist, educator and researcher; he is an architect and artist, a couple in private life, their bios are replete with artistic projects in Spain and internationally. During the last twenty years they have worked as an artist collective called Todo por la Praxis, which has evolved in a cultural space to rethink the city and embrace citizen activism.

Located in an industrial warehouse in the Vallecas neighbourhood, this place called Espacio de Todo “functions as our own workspace and simultaneously it is open to the community to address the needs of the neighbourhood,” says Peris. Critical pedagogy, research and participatory action manifests in a dialogue which nurtures their artistic production.

Their work asserts itself in practice rather than in theory, showing citizen co-production to build collective infrastructure for self-managed citizen initiatives defined in participatory processes. Their main theme is citizen activism applied to the commons and public spaces as an alternative to the neoliberal city.

The anti-austerity movement in Spain in 2011, also referred to as the 15-M movement, skyrocketed a change of thought, and with it, a raise in citizen activism. Urban dwellers began to have another interest in participating in the context of social movements and squatting, the practice of inhabiting abandoned or in-between-use buildings. From these spaces, where gatherings were open to the request and needs of neighbourhoods, the Madrileños began to question the city. People mobilised themselves and detach from the typical civic centre.

In this context, the artist collective started working in vacant spaces in Madrid. Today they are the well-known innovative hybrid spaces El Campo de la Cebada and Esto es una Plaza which have gained an official status through years of citizen activism. This work contributed to the evolution of their art practice into the urban fabric. The list of other interventions in tactical urbanism is long. Yet Todo por la Praxis always associates their work with all the urban problems that are emerging in parallel in the Spanish context, like gentrification, evictions and structural racism.

We saw the need to create other narratives in the city because migration is still not well understood, especially at a time when the far-right is getting more support in Spain.

This artist collective can be considered an urban mediator among initiatives arising from citizen activism and the administration. It also took part in the Cañada Plan in Madrid, one of the most iconic projects of urban rehabilitation and regularisation of the largest illegal settlements, and a pocket of extreme poverty, in a European city. In addition to the construction of common public spaces, they improvised a legal advice office for residents to help with the regularisation of their situation. Muñoz claims that “the gesture is itself an art work.”

“It is the way of doing things and their implication that makes it all an artistic project,” reveals Muñoz. Their work has a strong symbolic load that reverberates in its own artistic content. Both believe that Todo por la Praxis is “a laboratory of aesthetic projects of cultural resistance, a laboratory that develops tools with the ultimate objective of generating a catalogue for direct and socially effective action.”

Driving from the airport into Madrid another billboard on a major highway reads “Migrate is forever”. This symbolic articulation of suppressed voices onto the surface of the city intends to support the reconquest of spaces. Because it should be easy to be a newcomer in a city where so many people come from elsewhere but Madrid.