At the end of his career, the physician and playwright Wayne Liebman has painstakingly entered a strategic race to advocate for citizens’ assemblies – “throwing spaghetti to the wall, and waiting to see what sticks. If something sticks, it’s where I go” as he describes it. His frequent use of metaphors filled a spirited conversation over Zoom.

Liebman hadn’t been an activist to his core – the last time he was that active was during the anti-war movement – but the 2016 election left him with no other choice, he says. He retired from medicine and became a full-time activist. Nothing that he had anticipated.

He began to get involved, in a partisan way, to help regain some political power, at least, in Congress. But, in the midst of the storming of the US capitol, “as I felt like I had thrown a ladder at the castle wall,” he continues, “what I realized is that I have thrown it to the wrong wall.” Liebman’s deep exposure to elections and politicians made him realize that he couldn’t trust the system anymore, “in fact it was the system that had gotten us to the point where we were at,” he says.

According to RepresentUs, America’s leading anti-corruption organization, only 4% of Americans have a great deal of confidence in Congress. Significantly, a growing number of democracy advocate organizations are sprouting up around the world to fix, what they call, a broken political system. “Unfortunately what they mean by that, is to try to fix how elections work,” says Liebman. “But this is like lipstick on a pig.” Australia has already instituted all kinds of reforms and still Australians are completely dissatisfied with how politicians run their country.

Liebman started to read about direct democracy, citizens’ assemblies and lottery selected panels. While in representative democracies like in the US people vote for representatives who execute policies and laws, direct democracy models allocate more power to people because they include citizens’ recommendations into the policy-making decision process.

“I quickly became a convert,” he admits. In 2020 Liebman founded the nonpartisan nonprofit organization Public Access Democracy in Los Angeles to educate the public about democratic lotteries and advocate for the implementation of citizens’ assemblies. Currently, one minute at the microphone at an open City Council Meeting depicts a bizarre moment in a bleak democracy landscape. Introducing citizens’ assemblies — where a randomly selected group of citizens hears expert evidence then deliberates — would boost participation on difficult issues and solutions that people have already embraced voluntarily and have built consensus.

Ideally, the City Council has to consider it and respond in writing, especially if they don’t follow the recommendations report issued by the citizens’ assembly. Liebman wants other changes. The assembly should have policy-decision power, or at least, the assembly could come up with a referendum for the people to decide.

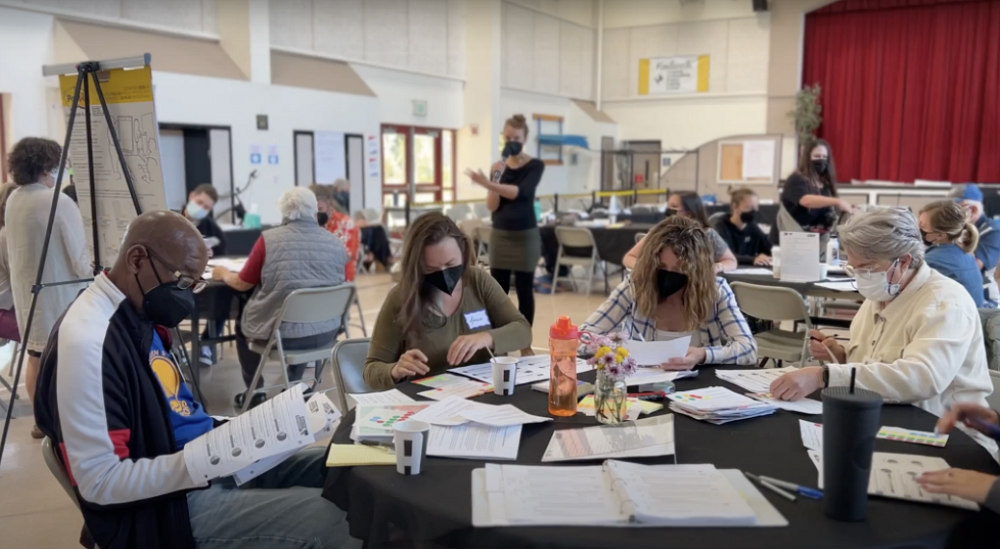

The question is: do citizens want to do this? Enough people would say no, says Liebman, even if the city pays and provides child support, assemblies would take people’s time for something they haven’t heard enough about. Nothing you can’t achieve with education. There is already a precedent. Last year the city of Petaluma, California convened the first municipal citizens’ assembly in the state through the efforts of Public Access Democracy, to recommend a plan for the future use of its municipal fairground — a contentious issue that had been plaguing the city for several years.

***

Remarkably, Liebman’s advocacy work on citizens’ assemblies focuses on the local scale. The launch of the initiative Public Democracy LA last year underscores his ambition to get Angelenos interested and excited about assemblies. He is also trying to persuade other democracy advocates in the US that civic society has a bigger role to play to win back the trust of the government instead of creating new ways of doing politics.

In the region of East Belgium, 70% of the people were in favor of citizen assemblies as a permanent part of the government, recalls Liebman, from a conversation with David Van Reybrouck, a Belgian cultural historian and author of the book Against Elections: The Case for Democracy. He speaks for a deliberative democracy based on sortition, a term that is familiar from juries. Deliberative democracy and participatory democracy are two leading concepts of direct democracy that cities in Europe have been exploring.

In the city of Barcelona, the previous government of the political party Barcelona en Comú experimented with participatory democracy by opening its electoral program to proposals from neighborhood movements and civic organizations. Newly elected leaders committed to a combination of neighborhood-level demands with a set of broader requests, from combating corruption to affordable housing. The Barcelona City Council even created an open source digital platform dedicated to participatory democracy called Decidim, co-founded by the European Regional Development Fund, to set up consultation processes such as participatory budgets, public surveys and calls for ideas.

Some members of Barcelona en Comú were from neighborhood associations and diverse social movements that helped to keep the channels of communication with citizens open; but this advantage came with shortcomings. Neighbors who didn’t vote for Barcelona en Comú did not feel represented in the participating process. “After two terms, the radical experiment in Barcelona has found limits to the project of bringing social movement energy into the corridors of institutional power,” wrote Mark Engler and Paul Engler at Dissent magazine. Their book This Is an Uprising: How Nonviolent Revolt Is Shaping the Twenty-First Century portrays a new generation that is unleashing strategic nonviolent action to shape public debate more broadly and force political change. Liebman thinks that citizens’ assemblies are the best way to do that.

In October 2022, the tape scandal in Los Angeles opened up a public debate about the future of the city’s governance. “People were up in arms,” says Liebman; “it was a good opportunity to make people aware of the democratic tool of deliberative democracy and democratic lotteries.” In December of the same year, Public Democracy LA organized the first meeting, and three months later, a luncheon with Claudia Chwalisz, the founder and CEO of DemocracyNext, a renowned international non-profit, non-partisan institute based in Europe that advocates for citizens’ assemblies. Ahead of her visit to LA, she posted on social media: “There is a political opening to think more imaginatively and ambitiously: Could a citizens’ assembly for LA help overcome the systemic problems of the city’s current governance?”

Yes, says Liebman, but to be effective both legally and practically, the citizens’ assembly would need official authorization from the LA City Council itself and have to be funded publicly. “We try to speak with people we know at the City Council, and reach through other groups that are lobbying for various causes like housing,” explains Liebman. One of the members of the coordinating committee at Public Access Democracy is Leonora Camner, a pro-housing advocate in Los Angeles who worked as Executive Director of Abundant Housing LA and is currently serving on the Santa Monica Housing Commission. But changing the culture of institutional politics is hard.

The other way to bring a citizens’ assembly through, explains Liebman, is to use direct democracy; “a ballot initiative can be an important tool for us going forward.” In the United States, a ballot measure is a law, issue, or question that appears on a statewide or local ballot for voters of the jurisdiction to decide on. Basically, if you get enough signatures on a particular petition, you could naturally ask for a ballot measure to vote on it. In 2018, Michigan overwhelmingly passed a law putting redistricting out of the hands of the legislators and into the hands of a randomly selected panel. It is the only politically powerful body in the US that is purely selected by a lottery. “Petaluma was advisory, but this one in Michigan has decision-making power. It is the one victory that we have in this country,” says Liebman.

***

In Europe, citizens’ assemblies still don’t have policy-making power, but experiments with deliberative democracy have come very far compared to the US. “We [in the US] are entrenched in wealth and power, yet it is clear that things are starting to happen. Personal freedom is what is important, but it has become all twisted and perverted. We have a lot of education to do in the US. If we have to fight for democracy, let’s fight for a real democracy,” claims Liebman.

I asked him how thin the line is between bringing ordinary people closer to the political decision makers process and still holding politicians accountable. They could always blame unfortunate policies on the will of the people. Liebman refers to the example of Ireland where citizens’ assemblies recommend a referendum on abortion, and politicians put it on a ballot following their advice. So, it is a combination, and he adds, “assemblies would be more representative than professional politicians can ever be. I would rather have a bad decision made by a politician who has been advised by a citizens’ assembly, than a bad decision taken by a biased politician.”

On the question of how to make sure that citizens’ assemblies by sortition (lottery) would fairly represent the whole population into the political process, Liebman bluntly responds, “There is nothing more fair than a lottery.” With a large body you would probably have enough representation. However, using stratification ensures that people of a particular group get randomly, but also proportionally, selected. These are all well-known techniques. “The other important issue is how to decide which kinds of groups should be represented in the citizens’ assemblies, and this, unfortunately, can take you into political territory.” Therefore he suggests getting a large body that allows enough people to get represented by chance.

I wonder how social movements or activists would find their place in this participatory ecosystem. “It is built in,” says Liebman. Citizens’ assemblies give ordinary people the adequate educational materials and time for an open debate. Activists could make their case in front of the assembly, as they would make their case in front of a jury, in a transparent and independent way as part of the educating process. The UN Democracy Fund has issued a handbook about best practices for democratic lotteries that includes the selection of background materials and speakers at assemblies as well as the role of facilitators.

Strikingly, the outcomes of the assemblies could be less polarized. It is empirically proven that when ordinary people with no agenda have to come up with recommendations, everyone moves around to the middle. “All the extremes go away, and ordinary people come up with workable solutions that everyone agrees with. That is what happens, when you get rid of the politics.”

All the work that Liebman and his team are doing at Public Democracy LA is voluntary, functioning without the constraints of mainstream advocate institutions. However, Liebman says, they will need funding for their advocacy work in the future. “An assembly in an LA adjacent municipality might be close. Their City Council will vote on it in the next few months.”

Already big think tanks like Berggruen Institute have supported some of their events. Public Democracy LA will participate on a panel at the American Democracy Summit. “The event is a fertile soil and we hope to put seeds into the ground. We will have several meetings and persuade people that citizens’ assemblies need to be an arrow in democracies’ quiver,” Liebman says towards the end of our conversation.

Now retired, this is how Liebman wants to spend his time. He hopes that the concept of citizens’ assemblies gets so rooted in LA that citizens accept that they will participate in an assembly at some point in their lives. Finally, I ask him if a local citizens’ assembly in LA is part of a larger governance vision at other levels around the country. “This is back to throwing spaghetti at the wall,” he says. “Petaluma was a piece of spaghetti that stuck. Let’s see if we get this other thing in LA that sticks.”