During the French Revolution, a drawing of Marie Antoinette had her face superimposed onto a dragon-like creature, which was supposedly captured in Chile and shipped to France. The French called such an unfounded rumor or story – today’s fake news – a ‘canard’. Canards spread widely, and the image disparaging the queen contributed to her surging unpopularity. The rest is history.

The equivalent of these “canards” can be found today in social media platforms that have become primary news sources for many. Deepfake technology, which uses AI to make synthetic audio, video, still imagery, and websites filled with untrustworthy information, has also branched out into political arenas. A deepfake video of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky surrendering to the Russian army was briefly circulated by malicious hackers before Ukraine’s national television station removed it.

Increasingly, people – and in particular Gen-Zers – choose YouTube and social media as their news source. They are inundated by online graphics, which when cobbled together with screenshots and reposted information, makes it nearly impossible to check the original source. However, researchers Nadia M. Brashier and Daniel L. Schacter found that older adults were disproportionately exposed to fake news sites as they analyzed the amount of fake news that circulated through the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. Surprisingly, adults over 50 were more likely to be “supersharers,” responsible for 80% of fake news shares.

Also, the Propaganda Research Lab at the University of Texas at Austin reported that communities of color and diaspora communities are targeted with “unique strains” of electoral disinformation intended to alienate and disengage them. This was the case with voters in Georgia during the 2022 midterms. Bot Sentinel, the analytics service founded in 2018 by Christopher Bouzy to track disinformation, inauthentic behavior and targeted harassment on X (formerly known as Twitter), picked up on messaging intended to sway Black voters to think elections are pointless or dangerous, and their participation as unnecessary.

As poisonous tweets and rogue posts proliferate across digital media, it’s become a formidable task to know what’s real and what’s not. Misleading stories and graphics are increasingly difficult to debunk. According to a co-authored study last year by Northwestern, Harvard, Rutgers, and Northeastern universities, only 8% of nearly 25,000 Americans correctly identified all false political claims presented to them. Similarly, an Ofcom research estimated that 30% of UK adults who go online are unsure about, or don’t even consider, the truthfulness of online information.

Social media companies have their own way to see things. Meta’s Transparency Center describes that misinformation, unlike “graphic violence or hate speech,” cannot be strictly prohibited unless it is explicitly harmful to others or directly obstructs political processes with the use of “highly deceptive manipulated media.” Policies like these may seem confusing to some users and highlight the precarious line that social media can walk. Although X has similar policies which state that they limit or remove misleading content, the non-profit organization Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) has cited a recent uptick in hate speech online. The CCDH has raised concerns that verified X Premium users have more leeway in tweeting and sharing content that is hateful, and these users benefit from algorithmic amplification as a result of their paid subscriptions.

Google Ads has also been in the process of dealing with an influx of dis- and misinformation. Disinformation is defined as intentionally misleading information while misinformation is inaccurate but not always deliberately false. Google provides an exhaustive list of policies that prohibit the promotion of fictitious businesses, misleading designs that contain deceptive user experience patterns like disguised functionality and hidden costs, and the use of manipulated media to deceive or defraud users. However, ProPublica conducted a large study of Google ads and found instances where they violated their own policies by placing ads that contain unreliable information on health, climate, elections and democracy.

***

These practices and self-guarding policies, which apparently do not always work to combat online disinformation, have recently put social media platforms under greater scrutiny. The obstacles to achieving a well-informed society are daunting. False narratives could impair people’s trust in the media as a whole and could persuade individuals to make decisions that aren’t based on facts. But, as Jason Young, who leads Co-Designing for Trust work at the University of Washington, observes, one of the greatest concerns that we face is that “misleading information is creating new social divisions within communities.” He continues, “Our partners often talk about how there has been a loss of the very feelings of community that are so important to them. We are hopeful that our project can help rebuild feelings of trust within communities, and thereby bring people back together.”

The spread of disinformation in cities, and rural communities, has already shown its ugly face on the streets with real-world consequences that require community-oriented solutions and grassroots approaches to combat online disinformation on the ground.

So, two years ago, academic and community researchers at the University of Washington, The University of Texas at Austin, Seattle Central College, and the Black Brilliance Research Project, jointly came up with the clever idea of working closely with librarians. Americans still rank librarians and high-school teachers as some of the most trustworthy professions, while their trust in other institutions is at its all-time low.

The researchers began working with librarians and faculty in Seattle as well as rural communities in Washington state and Texas, and across numerous organizations: Black-led organizations, community organizations, a community college, and public high schools. Their aim is to develop school curricula, among other materials, that inoculate young generations against the allure of false stories.

“We think that education is an incredibly powerful tool, in that it gives individuals the ability to ask and answer questions, critically reflect on information that they come across, and more,” says Young.

In order to develop these resources, Co-Designing for Trust uses a method referred to as participatory design (PD) in workshops. The method is based on a democratic approach that designs solutions and educational materials in collaboration with the end users of those solutions – community organizations, librarians, educators, and students – who will end up using the materials in their teaching and learning. This helps “ensure that they provide solutions that can be easily and usefully integrated into the existing ways that they use to navigate information in their everyday lives,” says Young.

So far, they have produced several lesson plans for use in rural high schools and in community colleges, as well as a few guides to support teachers, librarians, and community organizations to teach about information literacy topics. In addition, they are exploring other unconventional formats, such as a Media Mentorship Night for high school teachers. This is an event where students are able to bring their families into the school to share what they have learned about information literacy. The librarians have also developed several fun online quizzes to get their community more interested in learning about information literacy topics, with more resources currently under development. Young says they involve library programming and a board game designed for Black communities.

***

In the fight against fake news, there is a growing interest in games and fact checkers. The educational news games Bad News and Fake It To Make It are designed from the point-of-view of fake news creators and help people refine their media literacy skills. Also, fact checkers like FactCheck.org and Politifact are dedicated to reviewing political news and social media for “factual accuracy.” FactCheck.org can be directly contacted if a person sees a bogus social media post or story circulating.

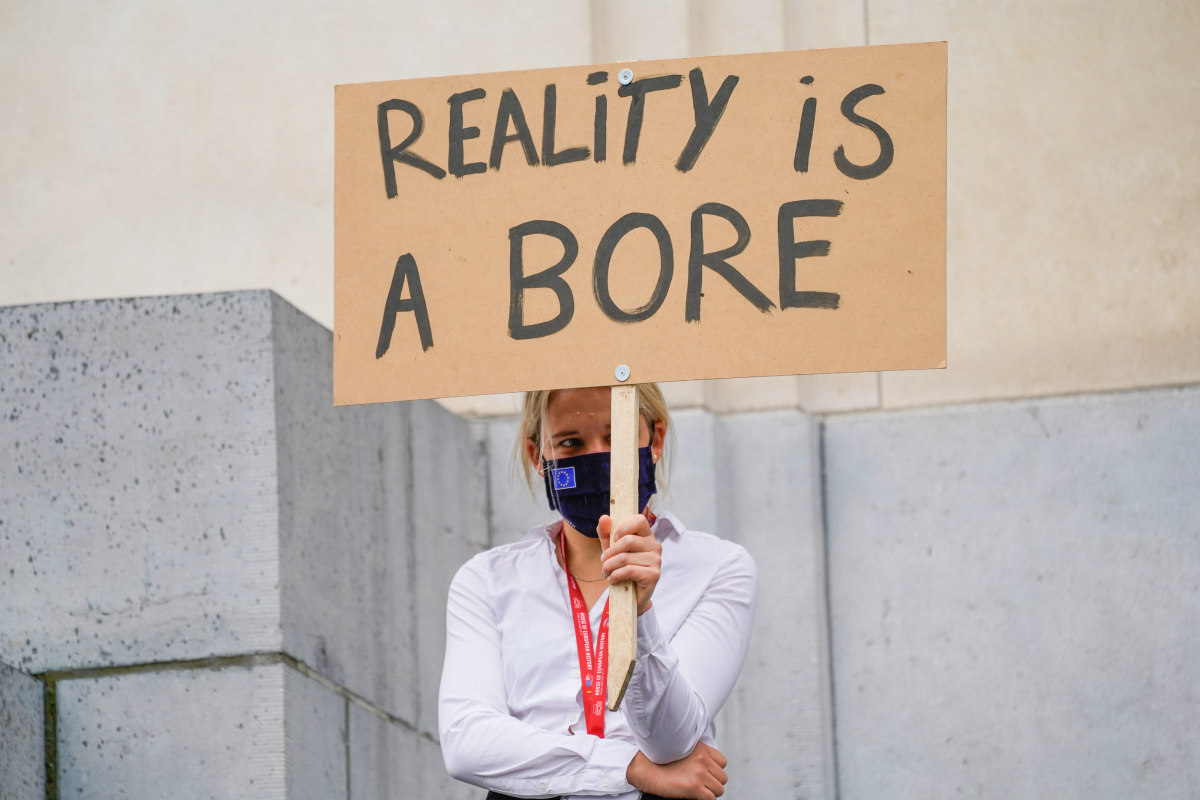

In the traveling exhibition Fake for Real – A History of Forgery and Falsification by the House of European History, participants were invited to take on the role of a fact checker to decide what gets published or censored. And last September, Ars Electronica in Linz, Europe’s largest festival for art, technology and society, aimed directly at the topic with its festival theme: Who Owns the truth? Exhibitors like theater group De Toneelmakerij, based in the Netherlands, invited visitors to put their own words into the video images of politicians and continuously played them during the event, so that “a lie told often enough, becomes the truth.”

To their credit, executives at Google, Meta and X have highlighted their own difficulties when it comes to combating online disinformation in real time, but they have also argued that the problem is solvable. Meta began training their AI-powered tool Sphere to detect online disinformation. Google announced they would expand their “prebunking” initiative to teach users to identify false information after seeing promising results in their Eastern Europe-based pilot. For this initiative, Google creates short informational videos that are featured in social media feeds and demystify known disinformation techniques like fear-mongering, scapegoating, false comparisons, exaggeration and missing context.

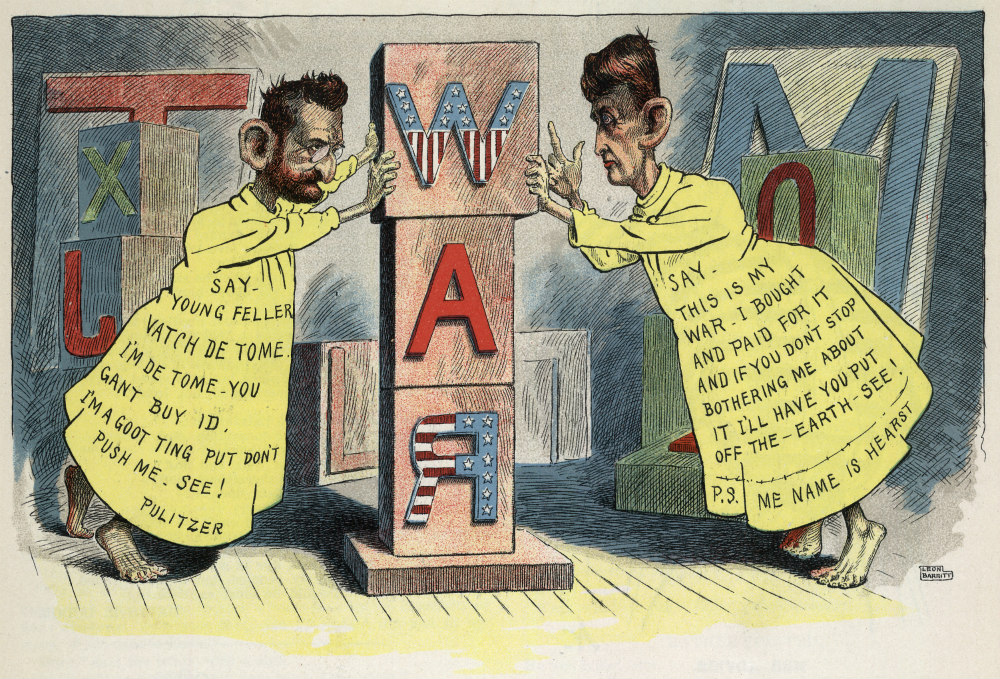

These strategies might help, but history has shown us that the public becomes vulnerable to manipulation when people are systematically exposed to propaganda and sensationalism, regardless of mitigation strategies. Through the Gilded Age into the 20th century, “yellow journalism” and sensationalist tabloids like the New York World, the New York Journal, and the National Enquirer, rose to fame despite being openly criticized for exaggerating the truth.

At the same time, objective fact-based news coverage worked in opposition to these sensationalist news outlets, and advancements in broadcast and print media were widely celebrated. These advances were later exploited, in the darkest of instances, by the Nazis who spread antisemitic literature, banned foreign radio, and tightly controlled newspapers, omitting the actual number of deaths or casualties that the Germans suffered.

Jacob Soll, a professor who studies how political systems succeed and fail, wrote that web-based news has seriously challenged journalistic norms while invigorating fake news. The other side of the coin are instances where politicians exploit or give their approval of fake news as a means to create skepticism around straightforward truths.

On the verge of the 2024 U.S. presidential election, fresh anxieties about dis- and misinformation are growing. Fact checking, prebunking and debunking interventions, ethical games, and AI detection– they all offer effective ways to combat the spread of fake news and protect democracies from online disinformation. However, grassroots approaches like Co-Designing for Trust foreground this ongoing battle spilling into our communities and requiring a collective effort, anchored in the everyday realities of how communities produce, consume, and interact with information. To cut through the disinformation overload, important educational work like this must be done.

This article has been co-authored with Susana F. Molina