Nicholas Okwulu shows two visitors around the Livesey Exchange LEX 2 building, a new community hub at 567 Old Kent Road. He is tall and wears a black beanie with a colourful African-pattern scarf. He spots me when I rush into the building, I am half an hour late but he greets me with a big smile in between his visitors. After a couple of months of following his work, I’ve been looking forward to this chance to talk to this community legend in the midst of the urban regeneration of South London.

A few days before we meet, his latest impromptu clear up most of his community work’s social media feeds. Sharing a photograph of a five-star hotel on Tooley Street where his college used to be, he touches on the process of change and exclusionary urban regeneration blighting Southwark, before closing with a call to “involve everyone.”

Okwulu graduated in Biochemistry right before new developments began to change the area between Tooley Street and the river as part of the urban regeneration of the Thames Corridor and nearby London Docklands. From the Tooley Street end there are spectacular views converging on Tower Bridge and the Shard is next door, but Okwulu remembers the area as one of the most run down places he had come across. “Little did we know about the future inward investment that was planned and the reason for running it down for ‘urban regeneration’,” he laments.

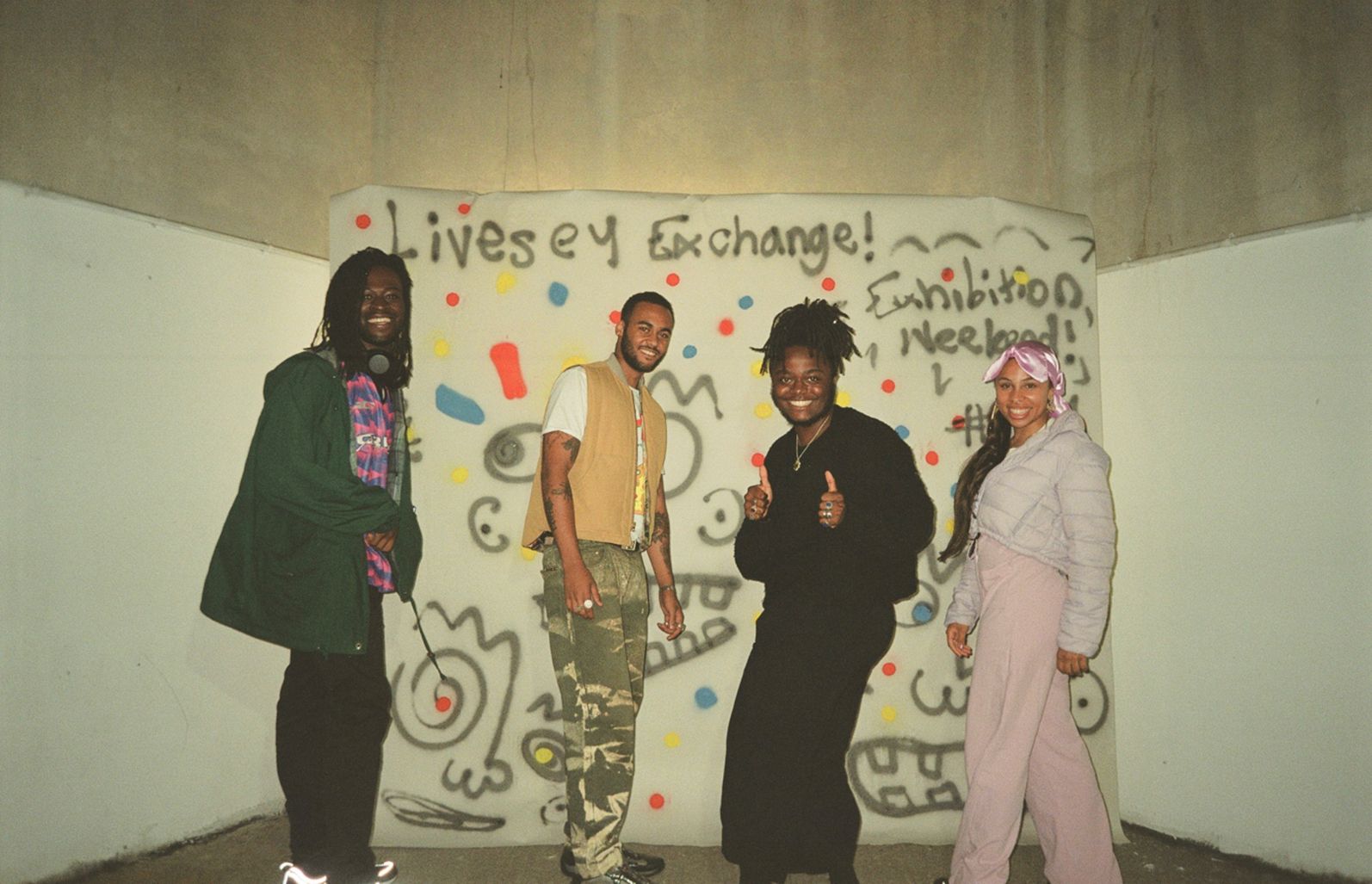

I am immediately struck by his practical way of putting things. I guess this is part of his success in providing tangible support for local residents to ensure their inclusion in the urban regeneration process of the neighbourhood. Okwulu is the founder of PemPeople, a non-profit organisation working primarily with local residents and community organisations from Southwark. Its list of projects include the Livesey Exchange to repurpose abandoned garages off the Old Kent Road into workshops, studios, multidisciplinary spaces, skill development training and cultural programmes for young local creatives to thrive. To that count the Southwark Untold at Tate Exchange, the Peckham Design Trail and the Southwark South Design District (as co-founder) as part of the London Design Festival working with local residents to highlight their creativity.

I am taken by Okwulu into the garages where I meet some of the tenants, all youngsters with creative endeavours; Tony runs Atom cycles, Wolf is a talented musician and Rasaq Kukoyi has a creative hub and production studio called Making Numbers and joined the Star Wars cast of Andor. “And so this is Ahmed, how would you describe yourself?” asks Okwulu. “Artist,” he responds. He welds and does design work with metal.”

There is a palpable fulfilment among the community, something akin to pride, that everyone has created an opportunity to be involved in something. But I sense, too, Okwulu’s acute mind at stimulating ambitions. “People have realised that even if I can help you, I won’t because youngsters have to show me that they can do it. And that’s what it boils down to. If you can’t do it for yourself, I can’t help you.”

“I need to be able to take you to the council or take you to the mayor’s office or put you in front of people that I’m meeting to say, look, I’m not the only person to see what you are doing and what you are supporting.”

The garages are a bit cold and not beautifully painted, says Okwulu, there’s not really any running water, but as he began with an exhibition, other things followed and realised that there were lots of people outside that wanted to find spaces like this. The council decided to hand over the keys to Okwulu.

And he has opened doors for many local youngsters. Many of them have already left the nest to go on and do greater things like Jaffar Aly and Kaytie Nielsen, who have both received grants from Arts Council England to host USB. He also supports people beyond the spaces he hosts, like Layla, a local girl who helped organise events for PemPeople pop Up Shop, who went to University to study Art and Event Management and is now working at the Tate Museum. “You just need to have that energy and ambition,” says Okwulu.

Above all, Okwulu wants dual purpose in everything that he does, like the Livesey Exchange LEX 2 building, one that, inside and out, expressed its mission to build capacity. A derelict lot sandwiched between postcodes SE 16 and SE 17 was sitting idle, until the Mayor of London and Southwark Council granted planning permission to Okwulu to build Livesey Exchange LEX 2. “But guess what,” says Okwulu, “this plot is on postcode one, it’s a central London postcode!” I admit that, by doing research, I had some difficulty to get a true sense of the area. Where the Livesey Exchange new building stands is like no man’s land. On one side there are new apartment blocks occupied by Caucasian whites, and on the other side mostly African-Caribbean communities.

Instead of pretending like there’s nothing happening around here [Southward], there are lots of talents in the community. Let’s show everybody what we’ve got. I’ve made it the busiest place.

“In all honesty, and this is how I see things, somebody planned this a long time ago. That’s why you got that SE one postcode in the middle of SE 15, 16 and 17. You know, people plan things and we’re not involved. And we, as a community, have to understand that this area was already ambitioned as part of a long term scheme,” says Okwulu. “So let’s showcase the diversity of the Old Kent Road ward and come and work all together because each side of the postcode has its own problems.”

With money raised mostly from the City Council and the Southwark Council as well as from private and local donors through Spacehive, Okwulu began construction to expand Livesey Exchange’s mission with a brand-new two storey venue on 567 Old Kent Road. Through its mix of accessible social, cultural and community space, “it will give local people an opportunity to be part of something that they thought was too far away. “

Okwulu asked his team to provide a kitchen where people could be offered culinary instruction to set up their food business and understand the logistics behind running a kitchen, on a rotation basis of one startup company per month. “In addition to people coming in and running the business for one month, I want them to sign a contract to go on a course to understand how to generate your business and to make it work.”

He also wanted an open cafe area where visitors can consume something to generate some cash, and people can stay and work here; and an alternative social space, where different charities and organisations can come in with the people they’re working with and use it, for example, for conferences, for theatre production – and they will pay for the use, financing the opportunity for others to do it for free.

I once read someone using the expression ‘Faustian bargain’ to characterise urban regeneration and what cities do to improve neighbourhoods that eventually drive out people who feel they don’t belong (and can no longer afford it). Okwulu’s long term vision wants developers and councils to understand “how do we get local people competing with people coming in and that they have the same opportunities. So you are gonna give the community this space for nothing now. But in two years’ time, there’s gonna be demand from the local people.”

“Instead of pretending like there’s nothing happening around here [Southwark], there are lots of talents in the community. Let’s show everybody what we’ve got. I’ve made it the busiest place,” says Okwulu with a smile.

He has watched the local area go from the top 15% most deprived ward to being in the top 20/40% but this improvement has been based on more people moving into the area as opposed to beneficial opportunities for local people to get on the ladder for home ownership, employability and other factors.

He is aware of the problems that come with urban regeneration in deprived communities, lack of generational wealth and support, sometimes lack of education, thus his argument is about tackling inequality on the ground. He thinks developers should be coming in and openly saying, “okay, you know what? We’re going to change the area, so how do we empower local people so that, when we build our tower blocks, we can move people in there because they can afford it.”

The fight to keep a foothold in the neighbourhood spreads out into public space. Walking along the Old Kent Road he points to a club strangled in between construction sites for student residences. Even if promises are made to local businesses and believe they can return, “they’re gonna close it down because they’re gonna turn around and say, it’s disturbing the students, but who was here first?”

Okwulu doesn’t like using the word gentrification, not because he doesn’t believe in it, but because it is a done thing. He prefers to use urban regeneration, so let’s benefit from what comes from it. “What we need is a proper way of developing community within urban development and with developers, that also applies to councils which often give the job to people who don’t really understand communities. Community’s work is not a nine to five job.”

“Unfortunately sometimes we [communities] need to justify our entitlement. But so far I’ve justified mine. If you wanna work with me, we’ve got all these young people with great potential. But you know, I’m showing people that I don’t have money, but I have social value.” Okwulu says he likes to moan, but the difference is that when he moans, he already has a solution.