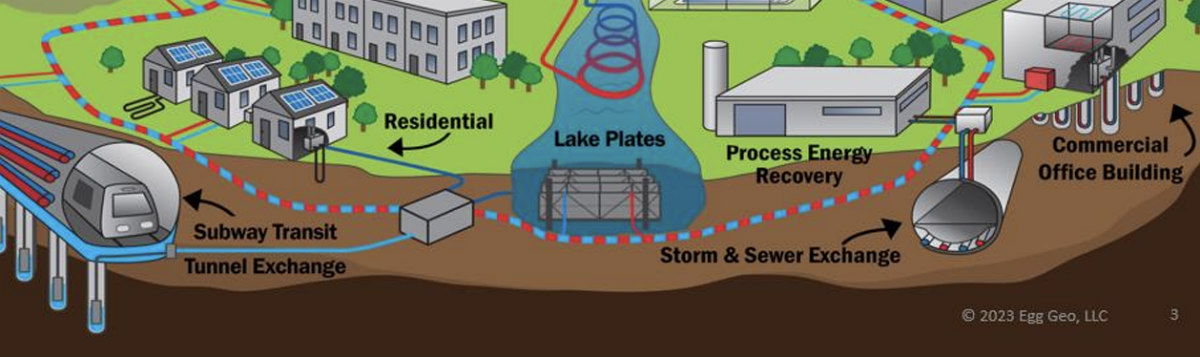

There is this one spot, on the verge of my neighborhood’s park, where people sleep rough at night; in winter, it’s surrounded by snow. The secret draw is that underneath lies one of the subway ventilation gratings. The subway, data centers, supermarkets, and hospitals, all produce tremendous amounts of heat. Cities are already onto this. In New York, residents’ plans to harvest “wasted” heat in thermal energy networks has galvanized city policy makers to decarbonize heating and hot water.

Remarkably, activist groups in New York are on another stage of climate action; a change of mindset and direct action got them ahead of gas operators. It was engineer Buckminster Fuller, who said “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete,” cites long term activist J.K. Canepa as we talked over Zoom a week ago.

Canepa is a member of the grassroots organization Sane Energy Project, born during “Occupy Wall Street,” under the climate group “Occupy the Pipeline” that opposed a gas pipeline coming from New Jersey into West Side Manhattan. For decades, New York landowners, neighborhood residents, community leaders, and anti-fracking activists have been opposing the construction of new pipelines. These actions felt urgent to stop the expansion of the fossil fuel industry. What gas companies did not anticipate is that these feisty New Yorkers would successfully pivot over the years to the real fight: rate hikes.

“Gas companies are not making money off the gas. They are making money off the pipelines. If you can stop rate hikes, you can stop the infrastructure,” explains Canepa.

Last week, executives of fossil fuel companies attending the annual CERAWeek get-together in Houston pushed back against a rapid transition to green energy, amid the high demand and record profits. All that, despite world leaders’ pledge at the COP28 to “transitioning away from fossil fuels” and to tripling the use of renewables by 2030. According to another media outlet, “Industry leaders argue consumers are unwilling to pay the costs associated with a rapid shift to wind and solar energy.”

But hold on. Consumers in New York are confronting price hikes that, they say, are not associated with a shift to renewable energy, and instead keep subsidizing gas. Who is really telling the truth?

***

In 2012 Williams Companies began the process of laying a gas pipeline from several miles in the Atlantic, through a barrier peninsula named the Rockaways, and then under Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge and into the gas distribution grid feeding Brooklyn and Queens, in New York City, owned and run by the British multinational corporation “National Grid”.

Sadly, Superstorm Sandy struck that October and hit the Rockaways especially hard. The community there was stressed and exhausted, many of them displaced, and with no real opposition the Rockaway pipeline was built.

But a few years later Williams was back, this time with plans to expand an interstate pipeline fed by the fracking wells of Pennsylvania to run through New Jersey, right past Einstein’s former home in Princeton, and thence into the Atlantic Ocean. The sole customer for this gas was National Grid. This pipeline would have been trenched up to 7 feet of the sea floor, home of benthic organisms like mussels, clams and crabs, and its constructions would have released the heavy metals (copper, arsenic, lead) and PCBs that had lain beneath since the Clean Water Act stopped the dumping of household and industrial waste into those waters. In fact there had been a 20-square-mile “dead zone” so devoid of oxygen that in the early 1970’s Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute had deemed it possibly the most polluted waters off any U.S. coast. But the whales had returned in strong numbers, and the dolphins, the birds.

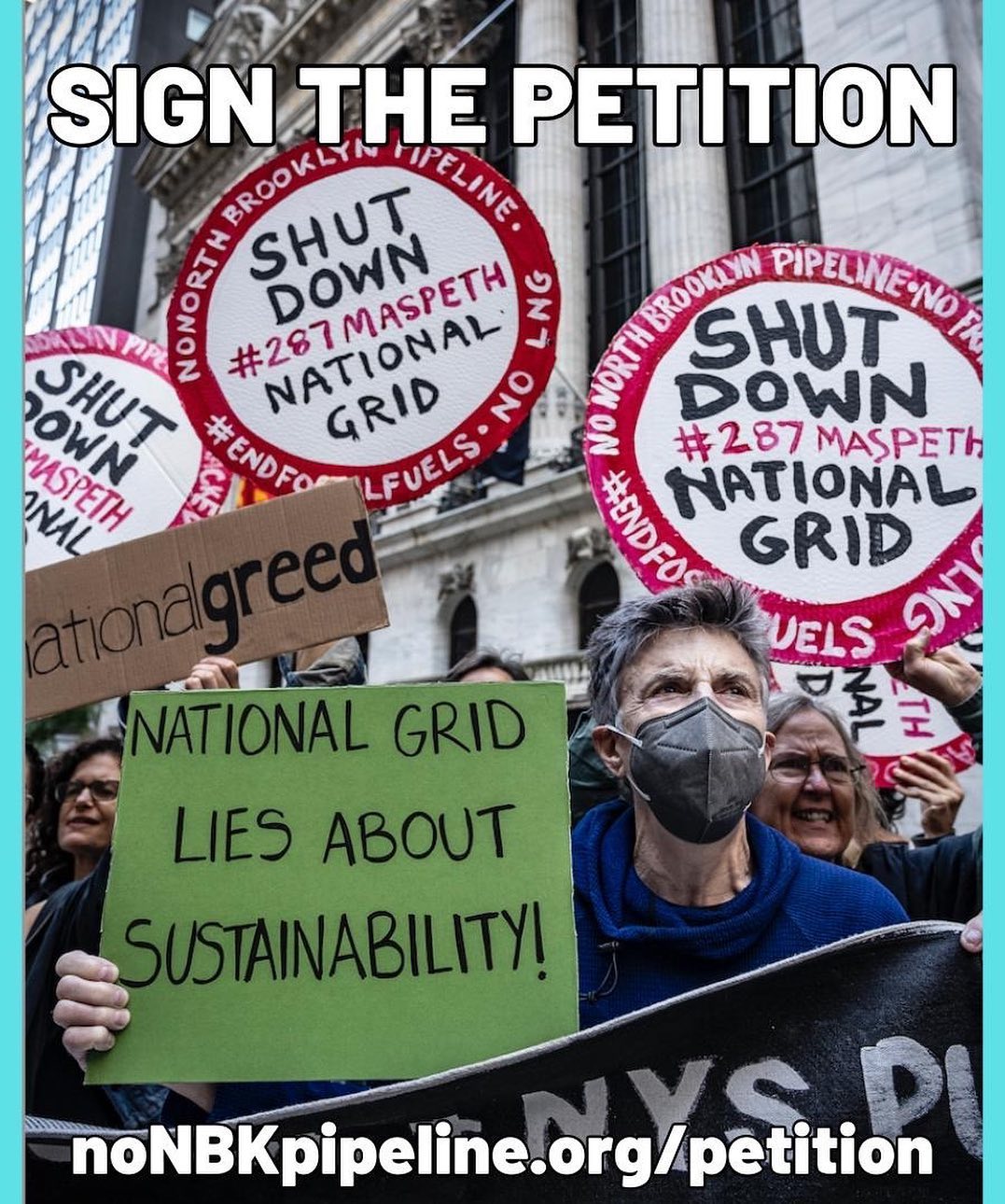

“Activists mobilized, people heard them and spoke up; community boards and elected officials joined the resistance. Tens of thousands of petitions were delivered to the state government. And We had a big win. We stopped them [National Grid]. If that pipeline would have been built, it would have damaged all that healing and all that burgeoning life,” says Canepa.

While activists were fighting the Rockaway pipeline, National Grid was nevertheless rolling out the North Brooklyn pipeline. This pipeline would carry fracked gas underground through predominantly low-income neighborhoods in Brooklyn (Brownsville, Bed-Stuy, Bushwick) and end at the LNG facility bordering Newtown Creek, a superfund site (administered under a program of the Environmental Protection Agency). “This area is so polluted that the deposit on the bottom of the canal is called Black Mayonnaise,” bristles Canepa.

When Kim Fraczek, Director of Sane Energy, found out about the existence of the pipeline and the rate increases in the gas bill for residents in the neighborhood, a lot of their efforts moved into the regulatory arena. “It used to be just the utilities’ lawyers talking to the Public Service Commission, the regulatory agency that oversees New York State’s electricity, gas, water and communications industries, and nobody else knew what was going on behind closed doors,” says Canepa. And she adds, “They would have never expected that the grassroots and the scrappy guys from the neighborhood would get involved. But we did. We sat through these interminable and very distressing meetings where you heard the lawyers arguing for higher rates, more equipment, spurious claims that repairs to intact pipes were necessary and that a growing customer base would need more and more delivery capacity,knowing that the Commission was already friendly to industry at the same time that New York was passing legislation to wean us off fossil fuels.”

Jessica Azulay, director of the group AGREE (Alliance for a Green Economy), guided Sane Energy, Canepa says, to take on rate hike resistance tactics as a way of fighting pipeline infrastructure. “It was a different world sitting in those meetings and listening to regulators and lawyers — one that required a whole different mindset and skill set than in the early years of Sane Energy.”

Canepa explains that, once you become an intervener, you’re not allowed to share what is going on in those meetings. But you can share non-confidential information with the public, and most importantly, you can ask the public to sign a petition. “You can tell the public: ‘This is the number that your utility company is going for and this is how much it would affect your bill’.”

Sane Energy and three other groups, No North Brooklyn Pipeline Alliance , Cooper Park Residents Council and Newtown Creek Alliance, achieved a second big win. “We stopped lawyers and regulators right at the last phase of the Brooklyn pipeline, and National Grid never got to bring the gas to the LNG terminal nor to expand that facility at the apex of where that pipeline was heading. However, they were able to increase the rate for fixing pipelines.” No North Brooklyn Pipeline Alliance is still working to shut down the sprawling National Grid LNG terminal itself.

“Now I’m getting down to the real story,” says Canepa. We started to alert the public about the infrastructure game of utilities and do teach-ins in places where National Grid as well as Con Edison (Manhattan, the Bronx, and Westchester County) operate. At that time, Con Edison was looking for a rate hike on electricity, and another one on gas, and Canepa reached out to the cooperative housing development where she lives, known as Village East Towers, a member of the Mitchell-Lama program in New York City (ensuring affordable housing that avoids the profit-driven housing crisis in the city). Together with Sane Energy, Canepa presented the story of rate hikes and then asked the neighbors to sign a petition, and the building’s board of directors to send a letter to the Public Service Commission opposing the rate hike.

***

In June 2022, New York enacted the Utility Thermal Energy Network And Jobs Act. According to this law, New York state’s seven largest utilities are required to pilot at least one and as many as five thermal energy networks as a test in the short term. If they do one project, it has to be in a disadvantaged community (if they do five, then two of them). “Our building falls in that category,” says Canepa. Con Edison and National Grid have already presented two thermal energy networks in New York City. The former is a project in a low-income multifamily residential building in Chelsea neighborhood where Con Edison will provide residents with 100 percent of heating, cooling and hot-water needs from a nearby data center. The latter is a thermal network for buildings owned by the New York City Housing Authority in Vandalia Avenue, Brooklyn.

And just last week, after a deep dive into this technology and funding strategies by Sane Energy’s Senior Advisor on Policy and Sustainability, Jeanne Bergman, Canepa’s neighbors voted to be part of a feasibility study for geo-thermal energy (with a long-term vision for a thermal energy network) that Sane Energy has consulted with one of the nation’s leading thermal engineering organizations. Canepa’s building comprises three towers and a pretty generous amount of open green space where the boreholes might go. The study is required in order to apply for funds from the Inflation Reduction Act, President Biden’s way of releasing money for the energy transition.

One might imagine that the plan of future thermal energy networks have slowed down gas infrastructure in New York, but the opposite is true. However, these are turbulent years for gas operators who are finding new infrastructure more difficult to justify and who keep growing their business and feeding investors. For instance, concerns over the health and climate effects of gas-burning stoves have also prompted the All-Electric Building Act in New York. This bill prohibits “installation of systems that can be used for the combustion of fossil fuels in new construction.” It applies already to new single-family residences and low-rise buildings under six storeys built after 2023, and for all remaining buildings it will go into effect in July 2027.

Right now, as we speak, the work is in the legislature, says Canepa. The remarkable feat of grassroots groups is that they’ve paved the way for three bills in New York. One of them is called the NY HEAT (New York Home Energy Affordable Transition) Act that prevents utilities from passing the costs of new gas lines onto existing customers as people transition to more renewables. Existing ratepayers, who can’t afford to put in a solar roof or can’t afford to deal with thermal, could end up subsidizing the whole gas infrastructure in New York. So the bill would cap the utility bill at 6% of the household income for low- and middle-income families.

The Climate, Jobs and Justice Package is a legislative roadmap to ensure a just transition for workers. The head of the Pipefitters Union, Canepa says, was adamantly against this transition to renewables because his union members were afraid of losing their jobs, now he is a champion of it. The bill will help create an accessible clean-energy New York economy that will benefit workers who switch to new jobs (thermal energy networks also require pipelines). And the Climate Justice Budget, part of that package, outlines $1 Billion in funding to critical, shovel-ready climate and environmental justice projects that are a must for 2024.

“If we can get these three bills in, we’ve pretty much got it,” says Canepa at the end of our conversation, who is in Long Island visiting her 100 year-old aunt. “She’s really something,” Canepa says. “She founded SmokEnders in the ’60s and got the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to take up her cause. Suddenly cigarette ads were off TV and off the radio. Then you couldn’t smoke on a plane, and then you couldn’t smoke in a restaurant. That’s her.” Her work transformed how we live. Now, climate change needs a similar upheaval, and is about to get it.