We are Natalia Bazaiou and Anastasia Noukaki, architects and also mothers working and living in Athens. Our experience of being mothers with small children in our city is of a place offering perfect weather conditions of living outdoors but extremely limited possibilities to walk without being threatened by traffic.

In Athens, due to the sprawling builtscape, commuting to the school is mostly by car rendering a fragmentary child’s urban experience. The departure and arrival points are clear to kids, but what about establishing a sense of spatial continuity? The result is a loss of connectedness with the reality of the city. In fact, children feel the city to be a largely unfamiliar territory of which they are not a part.

The need to enable children to reconnect to Athens for a more human and child-friendly city was what motivated us to set up our architecture and urban planning workshops walking with children called Athens Super Script.

The commute to and from school is a basic tool by means of which children may understand the city. In the eyes of children, it would be a magnificent journey of observation and adventure. These itineraries lay down the foundations of their topographical memory and determine the archetypes and symbols by which they will go on to interpret the course their own life follows in the world.

‘The child has not acquired yet that selective vision that distinguishes the beauty of the flowers from that of the weeds’, writes Colin Ward in his book The Child in the City (Bedford Square Press, London 1990).

Their gaze, unfettered by prejudice and stereotypes, is open to all sorts of possibilities. According to French psychoanalyst Françoise Dolto in L‘enfant dans la ville (Mercure de France, Paris 1998), ‘it is the child’s right to travel across the city on their own, as this provides the best possible training in being independent’. It would be ideal for children’s life in the city if they could experience it on their own walking through child-friendly circulation networks.

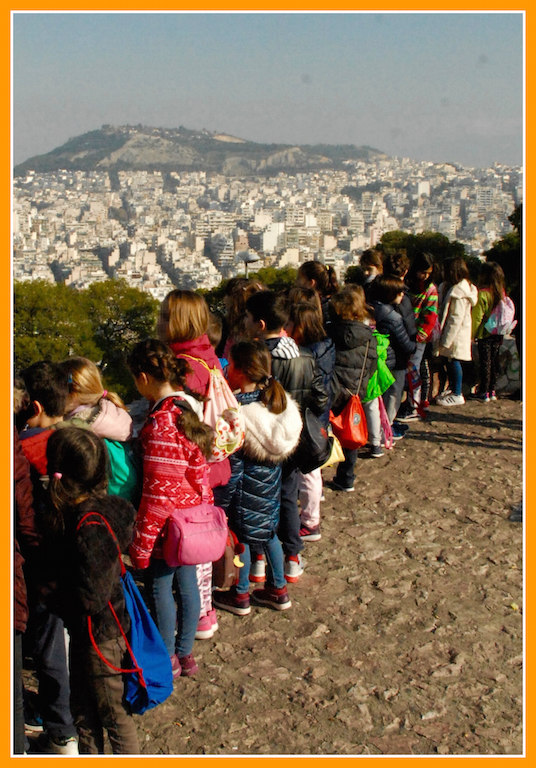

We walk with children in Athens and train them to look at the city with a keen and critical eye; to be inquisitive, vigilant and analytic in perceiving and understanding the urban environment. To find our place in the world that surrounds us we must first make sense of that world and invest it with meaning. The same applies for the city.

We want to train the immeasurable power of children’s imagination so that they can deconstruct mainstream readings of the city in the future.

One of our projects consists of connecting crucial urban places in a neighbourhood. Children are asked to trace the routes connecting e.g. their school to the park or playground, reclaiming the street and their right to move around freely and in safety. As a first step we walk with the team of children around the neighbourhood pointing places that can serve as points of reference or intervention. The final step would be to suggest their own interventions that mark their friendly routes.

In terms of methodology, the goal of the architecture workshops is first of all to turn children’s attention to their immediate surroundings and to encourage them to consciously observe them by focusing on their private spaces and on routes across the city they are familiar with.

The second stage, which we consider to be a fundamental step in the process, is building up a trove of representational tools, seeing as the boundaries of children’s representational language determine those of their world of ideas. Because, as Nelson Goodman would say, the world exists in as many ways as it can be described. In other words, there is a direct correlation between the representational means at our disposal and the information we can glean about the world. For this, we make use of a variety of media and systems of signification, such as aerial and on-the-ground photography, maps, mental maps, mapping techniques, collage, questionnaires, texts, constructions, illustration, not to mention encouraging a cross-disciplinary use of those tools.

At a third stage, having familiarized themselves with the process of observation and the use of expressive representational tools/media, children become aware of the power that a blend of different media affords them in generating new conditions and formulating new concepts and, by extension, in communicating these concepts to the world out there. Like play, which Julia Kristeva (1982: 32) describes as the fundamental vehicle available to children for transitioning from their own private universe to social space, art and its multiplicity of expressive means give children the possibility to interpret their immediate surroundings and, therefore, also that of re-interpreting them.

Children bring the element of experimentation to problem solving and come up with novel and unexpected approaches where emphasis is placed as much on the process as on the end result.

They practice identifying issues, investigating, evaluating and expressing their ideas in either 3 or 4-dimensional proposals.

Rather than aiming to foster a generation of future architects, we hope to create responsible citizens that acknowledge the importance of public space and are actively concerned about it; indeed, to provide an antidote to the dominant sense of apathy, indifference or ignorance by which the built environment is treated today.

Creating citizens that are not only actively interested in their world but also ready to go a step further by taking action presupposes an optimistic standpoint, a type of behaviour determined not by atavistic attachments but by the expectations we share regarding our present and future.