In 2012 Hurricane Sandy badly hit the East Coast of the United States, causing a power outage that overtook much of Manhattan. Some citizens were able to charge their phones and seek assistance thanks to a battery-charging bike, which now sits as a permanent fixture in the basement level of the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space. But it is also a functional fixture to step up to the occasion. The museum is a living history of urban activism that serves the community. Object and viewer wade in a new relationship that calls for direct action. The museum, or MoRUS, offers some clues on the notion of rethinking museums and their role in society.

The Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space lives up to its values against all odds. It was originally founded in 2012, by activists local to New York City, and particularly, the Lower East Side, like Laurie Mittelmann and Director Bill DiPaola, also founder of Time’s Up!, a volunteer-powered environmental organization focusing on expanding green space and bike paths for the last 30 years.

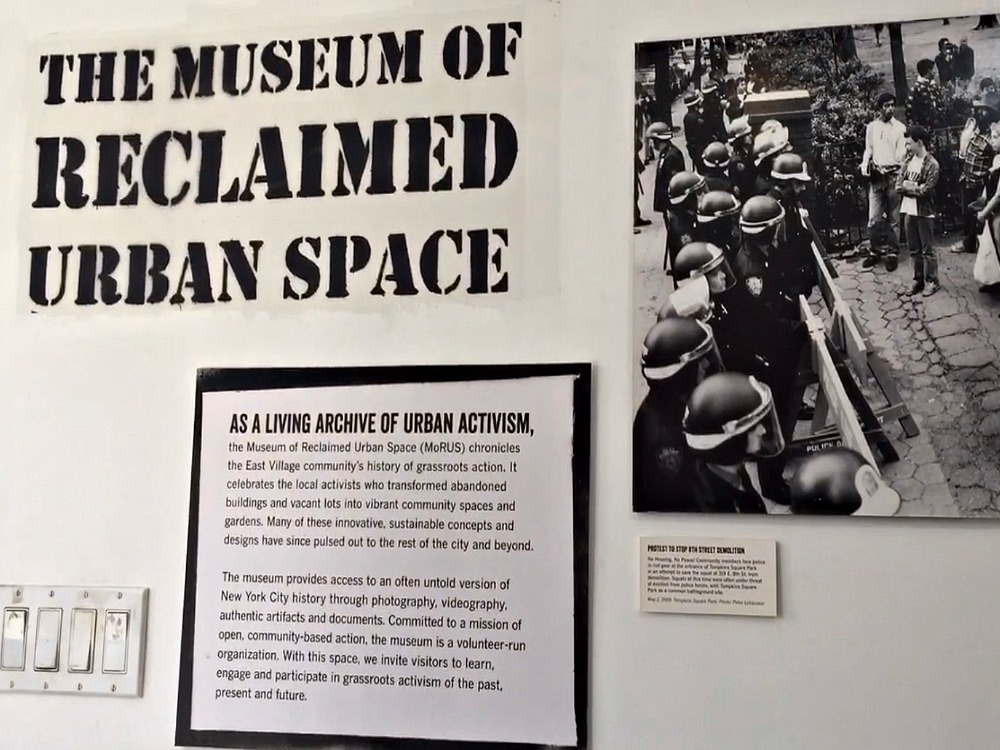

This volunteer-powered museum is housed in the storefront and basement of C-Squat, one of the remaining former squats in the Lower East Side. It preserves and chronicles the history of the neighborhood’s grassroots activism and celebrates the local activists who transformed abandoned spaces and vacant lots into vibrant community spaces and gardens. The museum is surrounded by the highest concentration of community gardens in a US city right in this area.

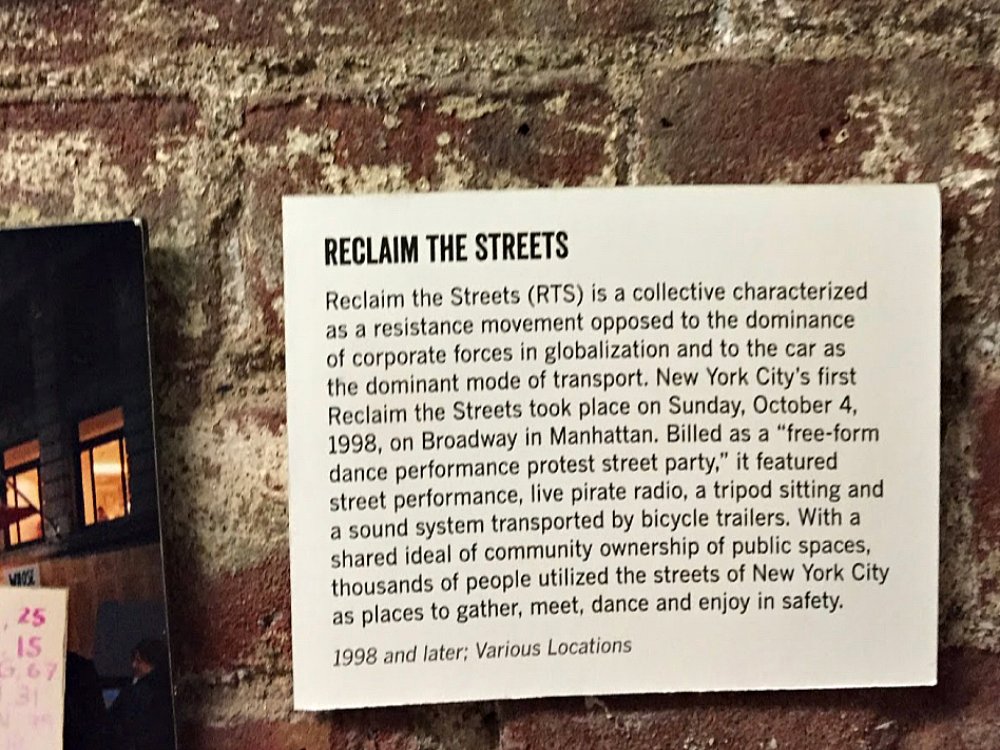

Many of these innovative and sustainable concepts back in the 1970s and 80s have since spread out to the rest of the city and beyond.

Who makes a museum? Rethinking museums to reclaim these urban spaces

Volunteers have refurbished the space, utilizing intimidating old police barricades intended to keep people out, and transformed them instead to invite people in. This shifting of physical objects is symbolic of how community members can take back power from oppressive forces and reuse materials and space to build camaraderie and inclusion. This is the same spirit that inspired local activists at that time to reclaim community spaces and refurbish them into community gardens and other collective spaces. The Lower East Side was revolutionized from dereliction, abandonment and government disinvestment. The museum is the story of space.

Museums have always been complex power structures: public-facing, and boasting literal treasure troves of information for engagement, education, and enjoyment for viewers around the world. However, this approach is often put forth with a lack of transparency on how these spaces are run.

There is an increased pressure for accountability that requires consideration of whom these institutions serve, and how best to make these spaces accessible for artists and curators as well as the public. While comfort can be found in the moves toward more inclusion, for those who have long been dissatisfied with the status quo, these incremental changes can often feel as piecemeal tactics or strategies to appease critics and dispel controversy. Current social movements such as BLM and Decolonize This Place call for much-needed overhauls to the current systems in place.

MoRUS works with community members in various capacities, ranging from the volunteer-run community gardens in the neighborhood; to yearly film festivals focusing on films with socially-engaged themes; to lectures with artists, activists, historians, journalists, academics, environmentalists, and more. Amongst the two levels are temporary exhibitions that go up seasonally throughout the year.

Upholding activist’s legacy to change the future

Every inch of the space has been put to use, as ephemera bursts from every nook and cranny; even the floor is covered in stencil art by Seth Tobocman. The original wall, covered in art and text from past residents of the building line one side of the wall behind the desk made from old police barricades.

The permanent collection contains archival photographs and other materials, ranging from newspapers to old electronics. Going down the stairs, each step is painted, further highlighting significant history. Videos play on monitors both upstairs and down, depicting important moments of how unity can lead to positive change. Pressure from activists led to bike lanes and more green spaces in the highly congested city of concrete; and education on how to stay safe at protests, and free education on housing and other rights are commonly programmed by volunteers and in collaboration with an array of other activists, artists, journalists, educators, academics, and specialists of the issues they expound upon on. The art on view is donated or on loan by local artists that were an active part of the movements the museum highlights.

The procurement of art and artifacts in collections is a troubling aspect of conventional museums. It is not enough to only care for the art or artifacts within the confines of the space, but to actively engage with those who are connected to, or creators of the work itself, and a responsibility to return objects that they did not acquire without question or protest. Since museums are a relevant part of the social infrastructure of our cities, they must be in conversation with whom they serve; making every effort to highlight the significance of the display. They should nurture relationships, trust, unity, and ultimately, build safe spaces to nourish and educate the public.

How can museums truly become a reflection of the very people it represents?

The key to the future of museums is already here. In order to dismantle the existing problematic structures of museums, we need to build our own. Through grassroots efforts, collectivizing, and staking personal connections that invite the public to actively build something in which all can benefit from equally, the public can take control of the monopolizing and capitalizing of what should be equally accessible to all.

Spaces that highlight community-based work through resilience and deeply rooted connections to the areas in which they exist are essential in determining the programming.

As part of the volunteer-run MoRUS collective, I have worked with other volunteers on many projects and organized events ranging from live shows to benefits, lectures, panel discussions, and more. The opportunity to learn directly from those who lived the history is powerful, and something unique to smaller and community-run museums. It is a form of empowerment, egalitarian in format, and memorable as an experience. Many of the activists who helped shape the unique history of the area have contributed in one form or another, to create something uplifting and inspirational.

The driving force is not monetary; it is about accessibility and equity. Mutual Aid is an important part of the soul of the initiative, collectivizing and using our strengths and resources to build the future we envision coexisting in together. In removing the power from elitist, corporate, and often questionable ethical structures, the public possesses the ability to truly invest in something that is built for, and by it. It restores and maintains autonomy and freedom when so often it feels like it’s out of one’s hands. When a community builds together, its strength allows it to stand against all odds and thrive in their hard-earned places and in the hearts of the communities they serve.