It is unusual to see activists, in particular female, attending the Munich Security Conference. But last weekend, some high officials and policymakers stayed until late – 10 pm on a Saturday – to listen to the all-women panel, “Rebels With a Cause. Voices of Civil Resistance”. Also, the panel “Sexual Violence as a Weapon” was entirely female.

It’s been a long journey for activist women to be seen as credible enough to be part of the Security Conference. Jody Williams and Maria Ressa won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997 and 2021, respectively, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya became an “accidental candidate” against the president of Belarus, Iranian journalist Masih Alinejad changed residences in the US several times on the FBI’s advice, and Burmese activist Zin Mar Aung became Minister of Foreign Affairs in Myanmar. Last weekend they were panelists at the conference.

Some of these women, like many others working on the ground, have engaged in mostly gender battlegrounds on the belief that the invisible enemy of patriarchy is deeply ingrained in the strategy of conflict and war. The question for the skeptics at the conference, holding their cards close to their chest, is: Could activists’ knowledge and experience with local communities and civil society in their countries play a vital role in reassessing strategies for sustainable peace?

On the last day of the conference I met with women’s rights activist and psychologist Dildar Kaya in Munich. She is part of the delegation of the non-profit organization Nobel Women’s Initiative where she was appointed to the interim Board of Directors in 2021, and has since joined the staff team. “At the conference there are representatives from international organizations like the UN, government officials and the like, but many are very detached from reality,” she declares, moments after we sit down.

Her resolute honesty and sentiment is arresting — at the age of 29 years old — and it serves a purpose: You can only spark real change if policies and security strategies are rooted in local realities. “We [the Nobel Women’s Initiative] are really trying to bring into the discourse the voices of civil society, particularly from local communities and local activists,” she says. I can imagine how effective her experience on the field in Duhok, Kurdistan, might be for the conference.

***

The city of Duhok is not a household name, but the region of Upper Mesopotamia where it is located might be. Once the starting point of civilization and the modern world, this region spreads today over the borders of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey – territories earmarked as Kurdistan. Kurds are the prominent majority population, yet the city of Duhok has always been home to diverse groups (Yazidis, Muslims, Christians, Jews).

Kaya arrived in Duhok almost four years ago to work in humanitarian aid on behalf of the SEED foundation. She lived with a colleague in an apartment in the city center, and jokes when she tells me that “we used to lie to people and say that both of us were engaged, so that we wouldn’t get a lot of questions” and stop the gossiping. She would walk every morning to the office or take a taxi, always changing patterns, “especially if you live alone as a female.”

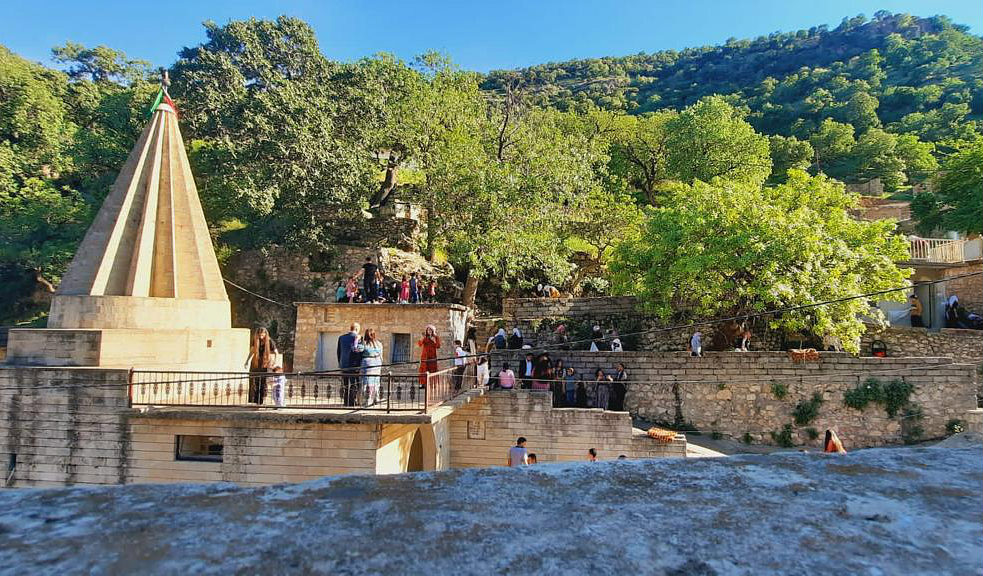

From the office she remembers the beautiful view of the mountains. Often she would go on weekend trips with one of the numerous hiking groups in the city and visit many of the beautiful ancient places in Kurdistan which are unfortunately not officially recognized as UNESCO World heritage, “but they have the same standing, at least for me personally,” says Kaya. In the city she enjoyed the great food, and tells me how surprised she was with the fancy interior design of restaurants and cafés.

It was not always easy, but wasn’t scary either, admits Kaya. Often she would spend time at the refugees and internally displaced persons (IDP) camps where she was working with women and children who survived ISIS captivity and sexual and other violence. While the towns of Sinjar and Mosul – both very close to Duhok – were parts of the region occupied by ISIS, Duhok has always been a kind of safe enclave in between the fighting. In 2014, due to the expansion of the Islamic State in Iraq and the aftermath of the massacre in Sinjar, the city of Duhok became a safe area for thousands of Yazidis fleeing the genocide.

In the aftermath of ISIS expansion, “if all went well in terms of information reaching women,” women who escaped from their abductors would know to go to the Survivor Centre as the first emergency point to get help. Initially built by an incredible group of local Kurdish women, and now supported by the government, this centre provides immediate access to services, like health services in case of infections, bruises, and other forms of bodily repercussions of sexual violence, psychiatric support as well as food and basic hygiene items.

Sometimes, if their families have survived, they will find them in the IDP camp and stay with them in the tents, which can get uncomfortably crowded with up to eight members of the same family. Then it was up to the families to decide how much support women can get and to what extent they wanted them to participate in the social activities and services of the camp, such as mental health and psychosocial support.

As a psychologist, and having worked before on social justice and gender equality issues with marginalized women and youth in Europe, Kaya assisted those women in the camp at the intersection of mental health and women’s rights. “One thing that we [Kaya and her colleagues] saw is that these women are not weak. They know exactly what happened to them. And they know exactly that it is an injustice. So I think then the question is, how fast do they speak up and to what extent?” says Kaya. And she adds, “I don’t like the word empowerment. I think women are already empowered, they just need to be resourced.”

“If you normalize the situation and if there’s support systems by the community and within the families, then they’re more likely to speak up,” says Kaya. She described how many women were very strategic and brave in the way they shared what happened to them through informal ways without putting themselves into a very sensitive or vulnerable situation. The same can be said of the women who were abused by their husbands. “The extent and intensity of stigmatization is significant,” Kaya reckons, as I watch her realize that they must remove a sign reading “psychosocial support” from the container in the camp.

“I think when it comes to the Yazidi women, they were incredibly bold and strong, because they not only revealed what happened to them, but also the injustice towards the whole community.” Nobel Peace Prize laureate Nadia Mura was one of the first few Yazidi women who brought international attention to the injustice, and thus put pressure on the government to ensure that these women could heal and rebuild their lives.

***

Yazidi women not only had the support of the international community, they also managed to get the support of their own community to be reintegrated at different levels of society. After the highest spiritual Yazidi leader understood the importance of embracing women victims of abuse, his consent spread across Yazidi communities in the IDP camps and everywhere around the region and beyond. “Some communities are more conservative than others, therefore it really depends on the community, to what extent they are willing to support the women. We tried to ensure that the community leaders, who are most of the time men, don’t speak on behalf of women, and instead women are present in the decision making of the community,” says Kaya.

The Kurdish region in Iraq is one of the key successes at the advocacy level. Internationally, Yazidi women are speaking for the survivors without a bigger agenda for a religious or ethnic community. The Iraqi government ratified the first law in the entire Middle East for survivors of sexual violence to have access to reparations. “Surely the implementation of this law is very tricky, as you can imagine, because it needs resources, it needs follow up in its monitoring evaluation. But at least there is political will,” says Kaya. However, children born as a result of rape remain a sensitive topic in those communities, although there is “at least a growing discussion around it.”

“I think it is important to understand that patriarchy is the issue here and the main reason why these women have been targeted by the perpetrators in the first place,” says Kaya categorically. Conflict-related sexual violence is not the result of unfortunate casualty, and it didn’t happen to women “just because they were there at that moment.” Sexual violence is not a by-product of war but a strategic tool based on patriarchy to sabotage communities.

Amid the destruction of war, perpetrators know that sexual violence is a weapon not only to harm the individual, but also to disrupt a social fabric strongly rooted in families. Instead of the perpetrators, it is the women who carry with them the stigma and the blame – be accepted by the family and no man could marry them. “So with sexual violence you stop basically the preservation of the whole community,” explains Kaya. And she adds “Yazidi women work mainly in agriculture and many have received just a couple of years of education or are illiterate. If women are abducted, they can’t maintain their communities during times of conflict. If young women spend several years in captivity, when they come back, there’s no way for them to go back to school and their ability to sustain their families with any skills in the camps is undermined.”

The recognition of sexual violence as a weapon of war by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda has been an important milestone for reparations. It has also raised the alarm among global leaders to take stock of gender-inclusive, feminist strategies in security and policies that could lead to stronger, more resilient societies and sustainable peace.

“I think the last days of the conference did frustrate me, because when you look at the current conflicts going on, everyone was theorizing and intellectualizing human pain and suffering. But how can we broaden the dialogue about what happens to the most vulnerable in these conflicts beyond the sexual violence component? ” asks Kaya.

She has attempted to instill working practices and experience of activists within the discussions of the conference. She tells me reducing gender violence to the sexual component of what happened to these women wouldn’t reflect the bigger issue when it comes to security and peace. Patriarchy has been a burden for women who would like to move forward as if “nothing” had happened. Security discussions at the conference, explains Kaya, have focused on more militarization as the key solution to everything, whereas she thinks that human security strategies, such as tackling patriarchy in local communities such as Duhok, could help evolve the defense paradigm and also guarantee sustainable peace.

One year ago Kaya returned to Germany. On a personal level, she wanted to take a break from humanitarian work in the field and join the Nobel Women’s Initiative. Her experience in Duhok made her “see the links between the power of Yazidi women and what is happening not only in Kurdistan but around the world,” she says.

“I wanted to go deeper into how we can ensure women’s voices and movements are more included in security and peace discussions. These discussions need to be led by women on a higher level, sitting at the table and making decisions, so that they are embedded into security and peace strategies.”

“When I listened to country representatives at the conference, I felt like there was so much substance missing. I think we’re really in a crisis of leadership, particularly in the West,” declares Kaya. It’s time for women to step in.