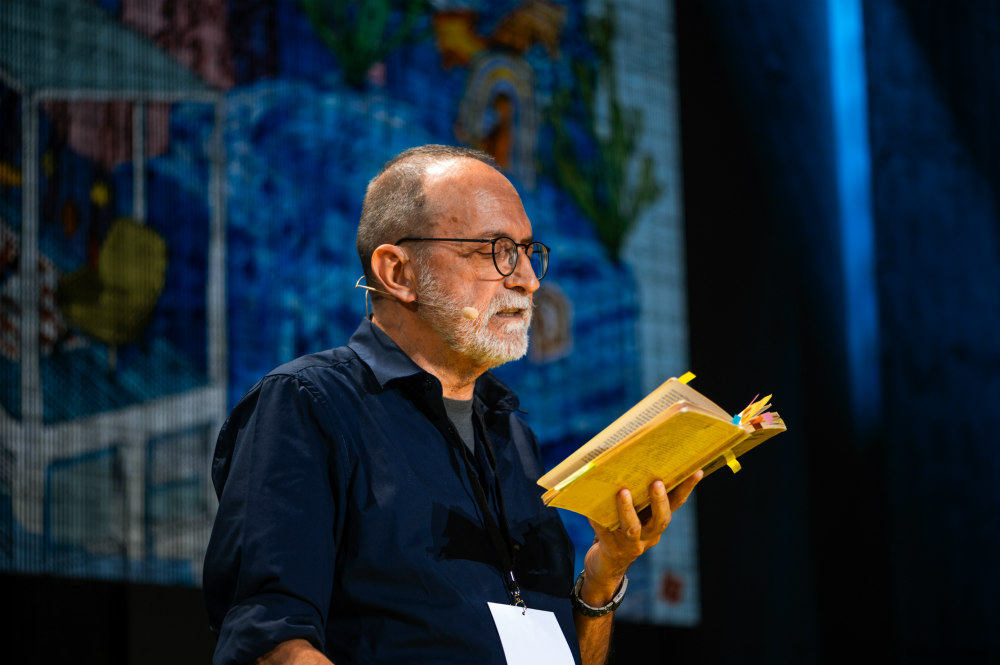

“Caspita, everything was already written!” exclaimed Giacomo Biraghi, after Italian theater director, Gabriele Vacis, read excerpts from Invisible Cities. We are at the international city-making festival Utopian Hours in Turin, Italy, organized by Stratosferica. Although in Italo Calvino’s masterpiece book, cities are imagined in a poetical way, there is nothing utopian about the festival, actionable suggestions to improve cities are not in short supply.

Calvino, who also develops a critical vision that questions the contemporary city, left us with “two options to accept the evil or to act”, added Biraghi. He, and co-founder of the festival, Luca Ballarini, choose to act. This distinct duo wants us to move away from normatively close urban concepts and to approach ideas that a priori seem distant or foreign. Utopian Hours is not intended to be a conclusive festival, but rather it aspires, says Ballarini, to “enlarge the education of city making,” seeking to actively position ourselves as agents of change involved in the cities we inhabit, as thinking beings who imagine, invent and create the future.

Fulfilling that educational goal, the attendance of the festival is young – an affordable ticket makes it very accessible for everyone – with a mix of students, international urban practitioners, experts and Italian city officials who gather at round tables. The program of Utopian Hours is intense but you stick to it, with an outstanding design (it’s no secret that Ballarini comes from the creative industry) and an intimate atmosphere at the Lavazza’s iconic headquarters, that one won’t find on red tape city conferences.

The founders also put their ‘impegno’ or engagement where their mouths are, with two interventions in neglected public spaces in Turin, the Precollinear Park (already dismantled), and Corso Farini, the latter in collaboration with the City of Turin and with the support of the international organization Cities4Forests.

Standing at Corso Farini, Ballarini said, “There are some places that are left by design,” and he added, “The municipality can’t take care of everything.” For many people, interpreting the city has meant filling in the blanks where the administration has overlooked people’s desires. The founders of the organization Sinny&Ooko were pioneers when they created Glaz’Art already in 1992, born from the restoration of an abandoned place as part of the underground scene in Paris who didn’t feel represented in the cultural scene of the city.

Architect and author of the book “Meanwhile City”, Petra Marko, built the case for the informal takeover of temporary spaces that could end up reactivating neglected parts of the city. “Cities are at crossroads with the future,” she says. Architect of the award-winning architecture studio OPEN ACT, Zuhal Kol, put her focus on the urban peripheries as crucial agents of change in Turin. They are the margins of the whole fabric of the city and embody the confrontation and friction between urban and rural, creating a dialogue between the natural environment and the city – issues that will certainly shape Turin in the years to come.

Currently the city is remarkably gravitating towards a new future due to significant allocation of investment to projects like the renovation of the behemoth building of the old Royal stables that will house cultural activities as well as offices. Turin has been trying to reinvent itself since it lost its industrial base, while it has continued to inspire an underground scene reminiscent of the industrial city that once was. STIPO’s first associate partner in Greece, Vivian Doumpa, nailed her presentation on the second day of Utopian Hours Festival, when she said “Please don’t touristify your underground.”

That same day at night I visited a metropolitan cultural center next to the large urban void of the former Vanchiglia railway yard, a former factory and the anti-aircraft shelter for the workers of the airport during the Second World War. Its experimental and queer vibe is very much what was Holzmarkt in Berlin twenty years ago. Two videos played at the festival by one of the Holzmarkt’s founders, Juval Dieziger, infused a nostalgic view of a Berlin that has waged battle to urban development. In an effort to maintain its existence, Holzmarkt has been left with no other choice but to surrender its experimental part.

Turin finds itself at this same pivotal moment. The Social Hub will open an urban campus in the city and use the growth of global higher education to attract talent to the city. “Before, manufacturing was in the city and people came to work, now you bring the talent and then the companies will come,” explained Frank Uffen, Managing Director Community and Partnerships of The Social Hub. Students are “transformative” for cities, something that he came to realize while Rotterdam was undergoing a difficult industrial transformation, yet students contributed 25.000 Euros per year to the city’s economy.

Uffen’s research on University City students’ populations is illuminating. Italy moved 5 spots into the top of 3 most searched study destinations in Europe since 2019. Already major Italian study university cities have seen expanding student populations. The Social Hub kills two birds with one stone, offering local administrations the opportunity to transform neglected buildings, while expanding students’ accommodation with new hybrid spaces in less developed neighborhoods.

The contributor to the festival with a big buzz around him is visionary entrepreneur in the real estate industry, Richard Upton, whose “purpose led regeneration” champions heritage and social inclusion in urban development. As Upton told it, “regeneration is the physical and spiritual renewal of things,” and therefore we need to change the culture of gross overdevelopment and unfulfilled promises of affordable homes. Upton illustrated the change by prioritizing an “external” rate of return in community-conscious urban projects. In that spirit, the speaker’s lineup of the festival hosted two state-of-the-art projects in the US, The Underline in Miami, and the 11th Street Bridge Park in Washington DC. Both grew from grassroots organizations into truly public-private partnerships.

In the second most dangerous city for cyclists in the US, advocates for The Underline in Miami saw the need to create a separate infrastructure that has repurposed the land below Miami’s Metrorail as the safest way for people to gather, walk and cycle in a 10‑mile linear park. “You can drive your Porsche to a condo, take the elevator to your apartment, and not see anyone. If you call that a Utopia,” says Patrice Gillespie Smith, former Senior Manager for Planning, Design, Resilience and Transportation at the Miami Downtown Development Authority, and now president of Friends of the Underline. In such an auto-dominated environment, “Miami is a very transient city, people move and don’t know anybody, these gathering places [at The Underline] are very important,” says Gillespie Smith.

When they opened the first phase in a wealthy part of the city, people were skeptical about the project which they thought was conceived just for rich people. But The Underline’s goal is “to make the space inclusive and accessible to everyone,” says Gillespie Smith. Even if real estate developers have already put their eyes on the increased value of the surroundings, “We are very conscious about displacement and provide affordable housing.”

She is not alone. “Acting early and intentionally is really critical,” said Scott Kratz, director of the 11th Street Bridge Park in Washington DC. The park will unite two separated communities, one significantly more disadvantaged, on each side of the Ancona river. In fact, an equitable housing plan for the community is well underway, with job training programs and funding to help black owned businesses timely prepare before the park opens, preventing gentrification in the neighborhood. All their programs are community-led, and most importantly, change moves, along with promises, at the speed of trust. “I believe this could be a model of how urban development takes place in communities,” says Kratz.

The most engaging contribution at Utopian Hours Festival came from Doug Gordon, activist and producer of the humorous podcast War On Cars. He played with the audience a game to imagine the most radical version of cities, a world free of cars, and at the end ask us to trade it for our current cities. It turned out to be a difficult barter. In 2015 Gordon found himself rebelling against traffic at Chrystie Street in Manhattan. “In less than half an hour and with about only $500 worth of cones and flowers, we were able to achieve something that often gets delayed by bureaucracy or political fear,” he said, and concluded that “We are victims of a world that we came to accept.”

Yet many people like him offer resistance and challenge urban norms. Ten years ago Marjan de Blok put a group of friends together to build Schoonschip in the canals of Amsterdam and created “the most sustainable floating neighborhood in Europe.” A project of this dimension found an ear in local city officials who were willing to support unconventional citizen-led initiatives.

According to Pablo Sendra, architect and professor of Planning and Urban Design at the Bartlett School of Planning in London, cities would be better off, he says in his presentation, if local authorities look at the existing social infrastructure, and find ways to build on these grassroots initiatives and incorporate them into the planning. He stressed the alliance between planners and activists as a way to transform from a closed city to one capable of adapting, laying the conditions for the unplanned to foster social interaction and contact.

Towards the end of the Utopian Hours Festival, he showed us a video where he discusses with Richard Sennet what is the role of the activist architect or the activist planner. “I think an activist planner mediates between social society and the state,” says Sennet. Hopefully, the Utopian Hours Festival inspires a new generation of activist planners and citizens who create bottom-up pressure for change critical to Turin’s future.