Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

A lot of things in Tangier’s historic part feel untouched by time. Walking along its labyrinthine streets, lined with beautiful houses, cafés, and bakkals, takes you back to the city where so many writers and artists spilled their memories onto ink and canvas for much of the twentieth century.

However, in an instant, that city isn’t immediately recognizable again and transforms into something new. As I walked from one of the doors of the Kasbah (fortified city) down to the Al Fahs door in the Grand Socco, I observed groups of young people in counterfeit brand-name t-shirts and football jerseys, others in djellaba, chatting, talking on their phones, or taking photos and videos. Once I reached 19 April Square, I cast a glance inside the iconic Riff cinema and saw that the film Palestine 36 was already on the program, while I passed festive sub-Saharan African fans — Morocco was hosting the African Cup this year.

It’s not only Tangier’s evocative time that attracts, but its unique personality and the unfolding of its daily life.

Even on a rainy morning, the flow of people was constant. I continued down Rue de la Liberté toward the Grand Café de Paris, where the self-taught Moroccan writer Mohamed Choukri, whose life exemplified resilience and transformation, first encountered French novelist and playwright Jean Genet. Once I reached Boulevard Pasteur, I easily found Khalid ibn Oualid Street, a pedestrian street in the Spanish quarter that used to be called Velázquez, that slopes down past an esplanade from where to contemplate the port as ships come and go.

In this little street, one could easily spend a couple of hours. Here are ARTingis, an art space and antique shop, and the Zawia fashion design store. Across the street is the well-known bookstore Les Insolites, which offers a carefully curated selection of books. Each book speaks its own language — English, French, Arabic — reflecting the city’s multilingual nature. Almost next door, large glass windows attract attention, and above them, a big sign reads “Kiosk.” It’s unclear whether Angelina Jolie visited this space last October intentionally or was drawn in by its striking contrast with the surroundings.

The first thing to note about Kiosk is its modern minimalist style: as soon as I step in from the bustling streets, I’m wreathed in one spacious room with big tables, chairs, and shelves, all in retro style, with mix-and-match colours, exotic books, and eye-catching posters. Design is the theme here: Kiosk is the cultural venue run by the agency Think Tanger, which hosts a variety of programming at the intersection of urban development and art, including a bookstore and a café. Although it is temporarily closed in preparation for this year’s program, I arranged an appointment with co-founder Amina Mourid and Communications and Graphic Designer Kamal Daghmoumi, who greeted me at the door.

Think Tanger is the vision of urban planner Amina Mourid and artistic director and curator Hicham Bouzid, both of whom have been involved as program mentors with organizations such as the Arab Fund for Art and Culture and The Prince Claus Fund, Netherlands, respectively. They have worked with the cream of funders dedicated to exploring new models that sustain arts and culture institutions in the Arab world. So why did Amina Mourid and Hicham Bouzid choose Tangier for their next venture ten years ago?

Tangier was in flux. After a long period of decline following its independence in 1956, the Moroccan government recognized the city’s potential and began revitalization efforts in 1999. That year, they established a new industrial free zone, developed a highway connecting Tangier to Rabat in 2005, and launched the Tangier Med industrial port in 2007. Furthermore, the introduction of a Renault-Nissan plant between the city and the port, which opened in a new free zone in 2012, along with the creation of a high-speed railway line to Casablanca, underscored the renewed momentum.

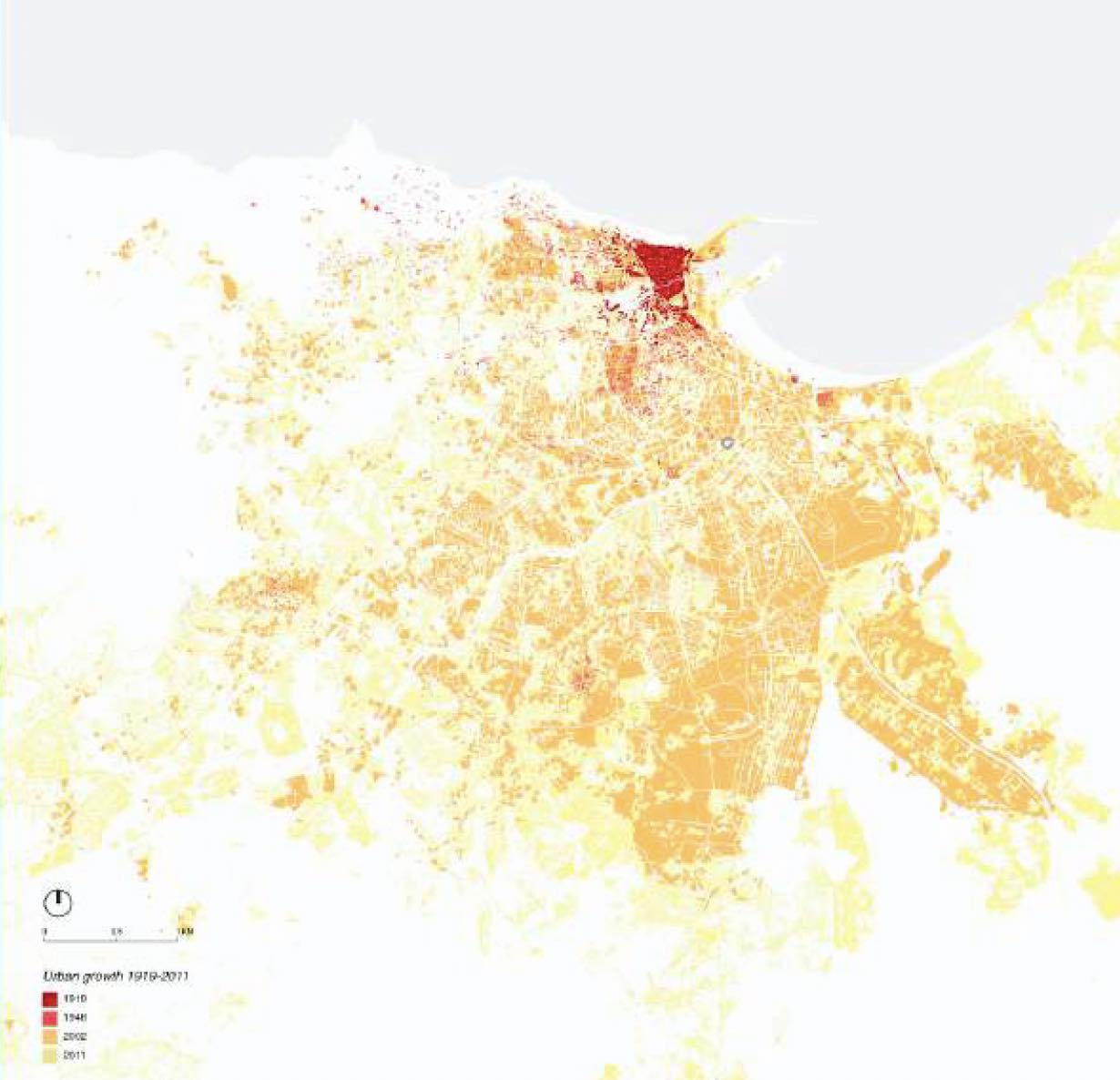

“We started 10 years ago as a seven-month project. The city was changing so fast, and we wanted to understand what the big urban project Tanger Metropole meant for the residents of Tangier,” explained Amina Mourid. By 2016, the population of Tangier had almost doubled from 575,000 in 1999 to 1 million, which led to significant social and urban issues, including a lack of transportation and the surge of informal settlements due to limited housing access. These challenges stem from a major gap in Tangier’s urban planning, where ambitious projects have failed to meet residents’ real needs, pushing them towards informal living conditions.

Recommended Read: Can Art Save Local Communities?

“Think Tanger emerged at a time that made total sense for the local creative community,” stated Mourid. She and Hicham Bouzid founded Think Tanger as a platform to engage artists, researchers, entrepreneurs, local communities, governments, and institutions, facilitating dialogue and innovation in urban development and cultural policy.

***

Today, Tangier’s population is nearly 1.4 million, and growth is expected to continue. One only needs to look around to see groups of young people on the streets, a constant presence in Morocco.

In September 2025, Morocco experienced the Gen Z protests, in which a younger generation took to the streets to demand sweeping reforms in public education and healthcare and to denounce misplaced spending priorities, such as international sporting events like the 2030 FIFA World Cup and the 2025 Africa Cup of Nations. Young Moroccans feel that the government’s top-down infrastructure projects and other expenditures do not adequately trickle down to address their needs.

“Our stance at Think Tanger is that urban development should be coupled with development in other sectors,” pointed out Kamal Daghmoumi. They aim to address these areas simultaneously by focusing on interconnected social issues and working at the intersection of artistic production and knowledge dissemination.

Ten years ago, Morocco initiated what is referred to as the regionalization of the state, explained Mourid. This meant that regional councils gained more power, budget, and responsibility for territorial development. This decentralization was significant because it allowed Think Tanger to engage more effectively with local governance. Mourid explained that Think Tanger’s ambition for the territory also reflects a modest understanding of the concerns of city administration, which must navigate budget limitations and security, a significant issue in the city. “Discussing the city is complex, with many perspectives involved. Therefore, we strive to position ourselves as partners,” she says.

Recommended Read: Saudi DJ Baloo in Riyadh: “We Still Think It’s Our Woodstock”

“We are well aware of our city’s political landscape, and we understand our country’s political model, including how the monarchy and the government function. For us at Think Tanger, activism is centered around education; it involves sharing knowledge and providing people with the creative tools necessary to reflect on changes in their urban environment critically and to formulate their own vision for the development of the country. Creativity plays a significant role in this approach. It is a dual learning process for us and the local communities we work with.”

For many years, Think Tanger has collaborated with local organizations in self-build areas in Tangier, such as the Zouitina and Bir Chifa neighborhoods, primarily through artistic mediums. In Zouitina, Think Tanger co-organized participative workshops with artists and social facilitators that encourage storytelling as a collective reflection of the neighbourhood, while introducing new ways of urban appropriation and development. At the same time, the community initiated several self-managed solidarity projects, including a mobile library, a cinema club, a football school, a singing club, and even a radio platform that invited members to share their motivations and achievements.

In Bir Chifa, they created StudioCity, a program that brings together artists, architects, researchers, and community organizations to promote a critical understanding of the living areas, with the hope of triggering a change in the living experience and enhancing a sense of pride and belonging.

“It took us ten years to build this network of partners and develop the infrastructure we have today — the Kiosk, the printing studio, and the residency program — along with the research and knowledge gained through working with local communities. We are in a very good position to become a true player in local governance, inshallah.”

Meanwhile, pressure has mounted on the local government due to youth-led protests, making organizations that work with younger generations an interesting reference point for local authorities to listen to. Think Tanger’s longstanding programs have served as a bridge between urban researchers and younger generations who want to engage in the future of their city and country. “I’m quite optimistic about Morocco, to be honest, even though we face many challenges. But we are in a moment of potential. I think this is the best time for Morocco to accomplish great things,” says Mourid with a smile.

Tangier, a city where two continents, a sea, and an ocean meet, and with a fervent young population, has every reason to reinvent itself. Mourid emphasizes that Think Tanger has been fighting the imaginary, exotic view of Tangier that was never made by or for the local people. They intend to develop a new narrative. That makes me think of the Moroccan writer Mohamed Choukri again, who, in his book In Tangier, without denying the city’s allure, strips it of romantic illusion. He does not reject Tangier’s complexity or magnetism; instead, he asserts the right to describe it on his own terms — as a place shaped by class, power, survival, and local voices. Much like Choukri, Think Tanger argues over who gets to create it and at what cost.