During Devin Allen’s show at Reginald F Lewis Museum in 2015, Robert Houston murmured to Allen, “Is your time now? Tell the story.” Allen tells me about his rare encounter with one of the great black photographers of our times, while reflecting on gun violence and police brutality in his hometown.

In 2015 he shot a photograph of the Baltimore Uprising against the police that went viral on Instagram and landed on the cover of TIME magazine. He remembers the youngsters at the front of the protest chanting for justice. Allen might have found his moment after outstanding feats of personal courage.

“By the age of fourteen I lost a friend to gun violence,” says Allen. This experience set him in a downward spiral and he ended up in the streets himself, yet gun violence will continue to take the lives of so many other friends. “Then I began to go on this kind of journey to discover myself.” Finally Allen found his medium in a camera that his grandmother bought him on a Best Buy credit card.

After that he had gotten into a big argument with a friend, who was still on the streets and didn’t like the change that was happening inside Allen. In the time frame of a few days, his friend ended up being murdered and another friend was shot in 2013. Two years later the murder of Freddie Gray happened through the hands of the police. Allen decided to go to the protest and shot that picture which has changed his life.

As journalists began reaching out to him to know what was really going on in Baltimore, he realized the power of controlling the narrative. “Often we don’t speak for ourselves, we are told by the media who we are,” he says with some resignation.

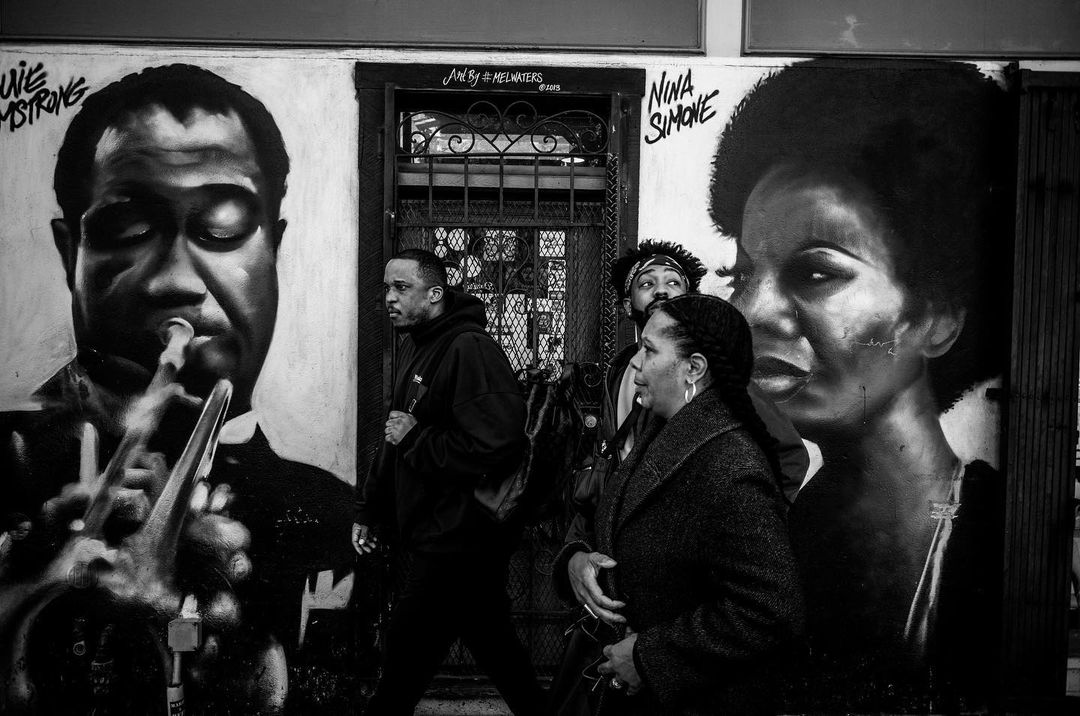

This is the second time I speak with Allen. The first time was when we met in New York, and every time I feel so strongly about his character. The same as with the imagery he creates, his modesty makes the life of ordinary people monumental. All together are the portrait of a resilient city on its own terms.

The camera has allowed me to digest the world and helps me with my ptsd and anxiety. I thought I can apply that to my kids, they have already experienced gun violence or have seen a dead body.

Economic depression, housing abandonment and drug trafficking, heavily concentrated within a small number of neighborhoods, has put Baltimore’s level of violent crime in a much higher position than the national average. Allen has witnessed it all.

“We grow with corner shops, and your mum has to catch 8 buses to buy fresh food. We couldn’t drink the water because there was lead in it, or there was lead in the house because of the type of paint. A lot of my friends grew up with behavioral issues because of lead poisoning, they had problems at school and as a consequence it was hard for them to get a job.” Born and raised in West Baltimore, Allen sheds light in places which have often not seen light before. He sees through his camera things that others don’t, the intimacy, the love.

“The camera has allowed me to digest the world and helps me with my ptsd and anxiety. I thought I can apply that to my kids, they have already experienced gun violence or have seen a dead body.” The kids he is referring to are his students. Allen’s involvement with activism doesn’t stop with the camera. He teaches, non-stop, numerous programs at schools under his initiative Through Their Eyes.

His youth program creates armies of young photographers to speak for themselves in their communities, sometimes on charged subjects, where arts education programs have been underfunded. And he adds, “photography was never offered in my community,” in fact, he was the only photographer living in West Baltimore. Allen has started to see the change in those kids because they can take a step back from the community and create their own safe space, away from gun violence, with the camera.

“When I walk into a classroom for the first time, kids don’t believe I am from West Baltimore, then I start talking,” says Allen with a captivating smile. “I am from where you are,” his accent reveals his provenance. “I tell them that it was my own choice to change my life.” Even when they are silenced by gun violence and police brutality, “kids understand they have a voice and they can take the fight in their own way.”

Allen donates cameras thanks to crowd-sourced equipment from friends and followers as well as fundraising. “Mister Allen, I still have my camera,” says one kid, tells me Allen, and he replies, “don’t call me Mister!” “I make them prove to me that they really want this. What kind of program would this be if you expose them to photography and then I take the cameras away from them?”

He tells me that “no story is too small, it is like a drop in a pond, look at the ripple effect it produces.” Kids are so transformative for the community but he acknowledges each community can be so different. Every time Allen goes to other cities to teach, he likes to arrive as an outsider respecting that community and adjusting to the circumstances. He doesn’t want to register his program Through Their Eyes as an official non-profit because it could never fit into the straitjacket of a definition.

Often we don’t speak for ourselves, we are told by the media who we are.

The public tends to think that every ghetto, community, is the same, explains Allen, but this is a common mistake made by those who want to help. The external voices are so loud that it doesn’t allow us to hear the internal voices. “A lot of people, non-profits, come to us and think they know what we need, but when we tell them what we really need, you get the same response. Well, this is what we have, and you have to take it or leave it. Coming from these places, like in West Baltimore, people ended up taking it.”

In 2017, Allen was named the first fellow of the Gordon Parks Foundation Fellowship and was chosen to serve as a 2020 Ambassador for Leica Camera AG. “I start to understand that I have social currency now, ” he says exalted, and he is in those same rooms that would have been denied to him in the past. “Now I have a platform and I can speak for so many people.” His powerful black and white photographs have been also featured in New York Magazine, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and in permanent collections across the US.

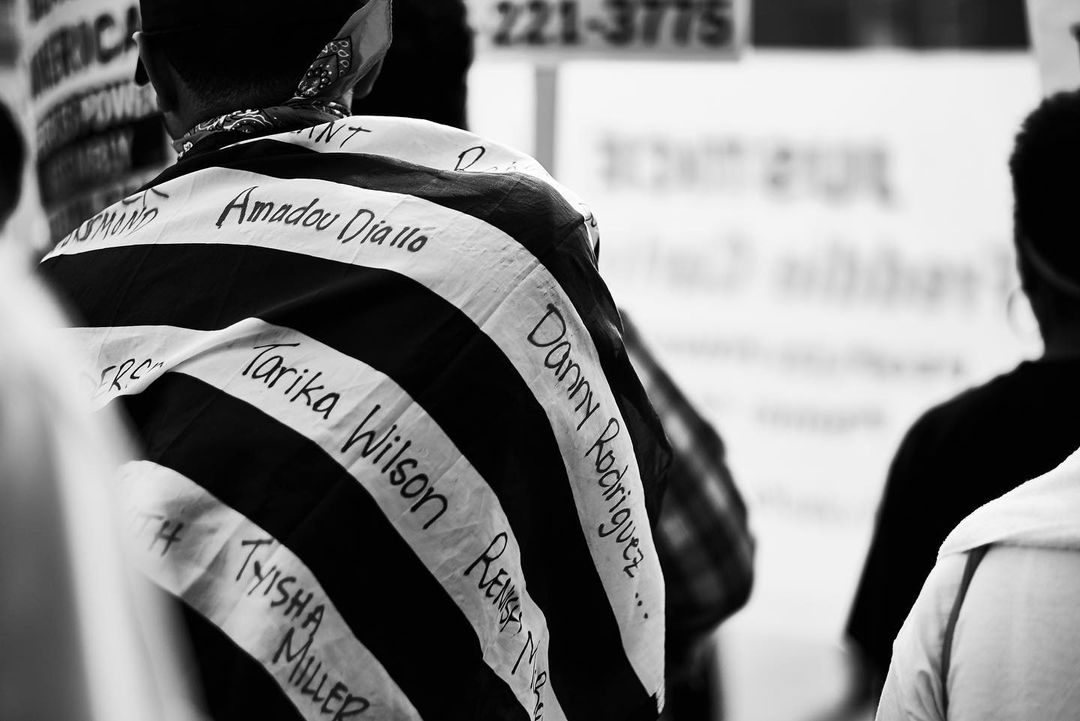

Allen found inspiration in great documentarians like Robert Houston, whose longtime mentor was Gordon Parks. Both documented poverty, racial segregation, among others, and the social movements around figures like Malcolm X or Martin Luther King. I asked Allen how he thinks activism has evolved in the last decades. His last book No Justice, No Peace: From the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter, in words and pictures, “honors the connection between activism today and that of the past.”

He speaks of how former black photographers intensely covered activism around all those polarizing figures. The Black Lives Matter movement is more of an umbrella term that has given black and brown people a voice and has set the reins free to fight racism in various ways. Each city has all these different voices, everyone can do their part, as he refers to his images from a Black Trans Lives Matter protest.

“I pick people that have a different way to fight and advance social justice. It is so complex and has so many different angles that you can’t speak for everybody.” Allen doesn’t take pictures which he doesn’t feel connected to. “With social media, it is difficult to be distinctive but you should stay in your own truth.” He picked up the camera aged 25 for the first time, ten years later he feels that his generation has to keep with the legacy created by all these “great black photographers behind us.”

Speaking from his apartment in Baltimore, he says there is no way he would move from the city. “I am living my wildest dream, I make images here, and I live to give back to my community.” When he is not teaching at school, he drives around Baltimore always with cameras in his trunk to give them away to kids. His work inspires swaths of emerging young practitioners, and “I am seeing an improvement in a new generation, becoming very powerful. I hope to be here to see how it evolves.” When I ask him how long he will run his program Through Their Eyes, he responds without hesitation “forever!”

Here you can watch the panel discussion that The Urban Activist and 1014.nyc co-hosted on urban activism with Devin Allen and other activists in New York.