On May 31st and June 1st the prosperous black neighbourhood known as Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was reduced to ashes at the hands of a violent white mob a century ago — deleting years of black success and suppressing talent. The violence and discrimination against thriving African-American urban communities altered the lives of their residents, the prospect of cities and impair the opportunity to change flat-white economic history. That unheard-of black capitalism has nowadays picked up pace in cities on a mission to create a more inclusive version of the American dream, essential for urban success.

Back in the day Tulsa’s Black Greenwood district as well as other neighbourhoods in cities became self-sustaining business hubs. Due to the influx of black southerners coming north to escape the racial segregation laws of Jim Crow, African-American doctors, lawyers, musicians, artists and entrepreneurs were forced into a few places, after being rejected of their rightful place in American society.

But for a twist of fate, that injustice made some of these places incredibly successful and resilient due to an extraordinary concentration of talent. Residents were helping one another build wealth with less stronger ties to the traditionally white male-dominated sources of capital, which have made it through history until today. No matter the wealth black capitalists would have stockpiled, it was always turned down by continuous racial attacks, perpetuating the black-white divide. Not only in Tulsa.

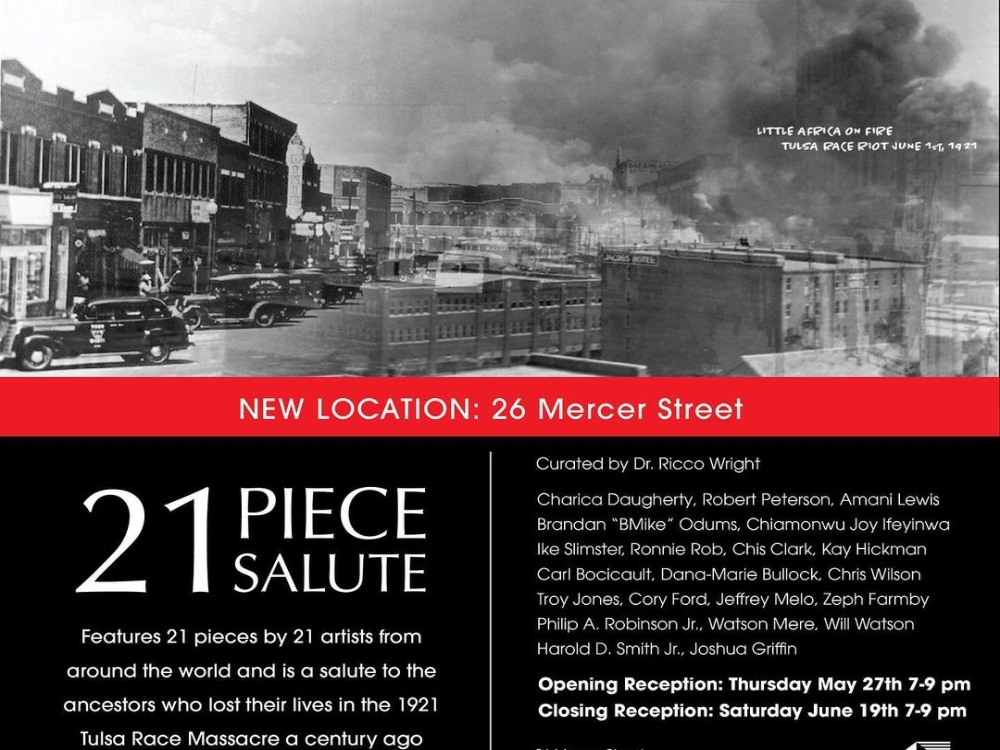

On this memorable occasion of the centennial anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre an ambitious exhibition, not far from Wall Street, features 21 black artists. The powerful pieces hanging at the Black Wall Street Gallery in New York are a salute to the ancestors who lost their lives in the massacre of Tulsa, honouring them and what they built in the face of Jim Crow.

The owner of the gallery is Dr. Ricco Wright, a fourth generation Tulsan, who I have been following for more than a year after I wrote a piece about his Black Wall Street Gallery in Tulsa. Since then his vision has made it to New York, where he has opened a new gallery in the SoHo neighbourhood during the pandemic.

Determined to create a community around black art and dignify the buried history of their African-American ancestors, he is shaking the art world in the Big Apple.

‘The 21 Piece Salute exhibition is also a way for us to answer the question of what we plan to do for the next 100 years. We’re not focused on the history of the massacre as much as we’re focused on building generational wealth for black and brown people through art, because back then the pioneers of Black Wall Street were preoccupied with group economics and black entrepreneurship, and today we are too. Every artist featured in the exhibition believes that black art is the future and today we’re in a stronger position to impact the art world’, explains Wright.

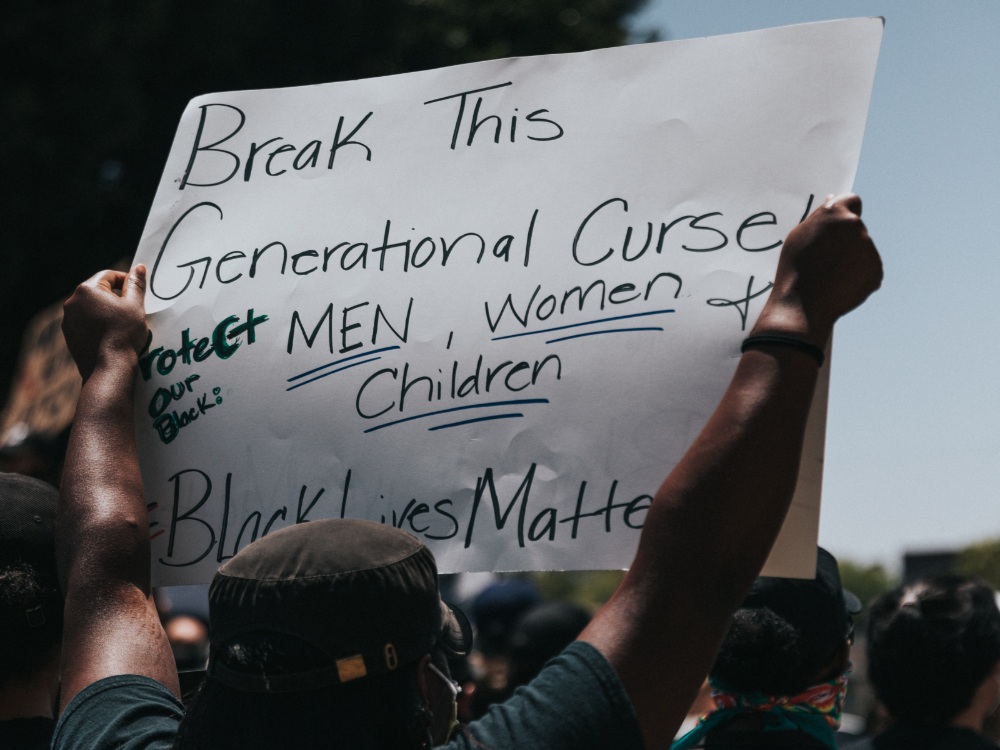

But also to impact the capitalist world. Wright is fulfilling an American Dream that will prosper by helping draw businesses to black artists. If Wright succeeds in his enterprise, his efforts are the promise of capitalism: social and inclusive. Black capitalism is emerging from activism taking on that blueprint ancestors left behind, not from capitalism, and from mass movements like Black Lives Matter.

A year after George Floyd’s death people participating in protests against racial injustice are also vivid critics of white capitalism making people less equal. Some US cities, especially in the Midwest, have struggled with entrepreneurship to diversify economies and attract investors. The region has particular problems with segregation and policing that make some neighbourhoods feel like American Apartheid.

Back in Tulsa, the Greenwood community eventually managed to rebuild some businesses after the massacre, little by little, but any possible future success was systematically destroyed by the urban renewal going on during the 1950s. The construction of highways cutting through cities isolated most African-American communities. Only in the last couple of years black urbanists are getting their voices heard about the inadequate city planning of US cities for black-owned businesses.

In the last years black entrepreneurs have rolled out businesses along Greenwood district as Wright did, however some feel disadvantaged by the lack of generational wealth or land ownership to build upon. They have to turn to mostly white capital that makes them less independent. It is no secret that many of the square blocks of homes and businesses that made up Greenwood are now owned by the city, the Tulsa Development Authority and the state university system.

It’s unfortunate, says Wright, that certain white people who claim to be our allies are profiting from our pain by turning Greenwood into a tourism and white-ownned hub.

‘Instead, what they could do is grant access to us for greater entrepreneurial opportunities, give us our land back, and make room for black developers to construct commercial and residential buildings in historic black districts. Otherwise, they’re just continuing to perpetuate white supremacy, maintaining their control and power in an effort to control narratives and the minds of the people’.

It is therefore not surprising that Tulsans are asking for economic reparations and restitutions. A move by the city of Tulsa in that direction would be key to acknowledge the importance of the independence of black entrepreneurs that could enrich the broader economic activity of the city. New structures should be built around the fact that the privilege of generational wealth that helps to start-up a business has been repeatedly ripped off from black and brown communities through history.

‘I know how important ownership is,’ says Wright. ‘For instance, after my lease ends, my landlord can say, quite simply, “We’re going in a different direction with this commercial space and therefore you’ve got to find something else.” That leaves me, my staff and everyone involved in a vulnerable position. Sure, I own the gallery, but I don’t own the building where it’s housed, so I’m still at the mercy of someone else. That’s why when we talk about building generational wealth, we also focus on ownership in every sense of the word’.

This year the Financial Times reported that black women entrepreneurs especially fight to stay afloat in the pandemic. They are the fastest growing start-up demographic in the US, but struggle to find credit. It is easy to draw conclusions about what this would mean for the overall US economy if they would have access to equal financial resources.

A report by a group of mayors noted that 86% of Americans live in metro areas, producing 91% of the national income. Capitalism has for too long whitewashed the important contribution to the US economy of the resilient economic activity of African-American communities and, as a consequence, the impact that it would have had for the prosperity of cities.

Efforts towards black economic independence and creating appealing conditions for black entrepreneurs can only foster the upward social mobility of black citizens and spread wealth, essential for overall urban success.

Some cities have already grasped the potential of black capitalism. According to a report by The Economist, Cincinnati is trying to spread entrepreneurial activity by getting more black businesses as suppliers to its biggest companies and Detroit has some plans to develop ten commercial corridors to spread the wealth.

In Kansas City I spoke to Tovah Tanner, who is retraining youngsters in black and brown communities the entrepreneurial mindset of a city that once accommodated numerous successful nightclubs with some of the best jazz players in the world.

In 2017 she founded with her son the non-profit organization Royale Cohesive Network to ensure young citizens cultivate and carry on the excellence that was set forth by their ancestors and pass on their legacy at a very early age.

I come from a tradition of entrepreneurship. My great aunt was a seamstress, who designed clothing for the LGTB community, local jazz artists, and everyday people in the early 90s, explains Tanner.

‘Growing up, I saw singers, entertainers coming and going and how my great aunt identified an opportunity to create a product that could service our community and manage both entrepreneurial life and personal life well. I have carried that experience with me.’

Her initiative is developing a platform for the youth to showcase their business among other fellow young entrepreneurs. She teaches them to hold on to each other for support. They build lasting and rewarding relationships within the community, consumers, local businesses, organizations and potential investors. The organization has got recognition from the Kansas City Council and the Missouri State for their positive impact in an historically underrepresented community.

‘Sometimes we are not aware of our rich black culture and of the importance of honoring our ancestors for our dignity and passing their legacy from generation to generation. We have already given so many distinct flavours to the culture of business in this country and shaped a lot in America. It has been time to elevate us as entrepreneurs,’ claims Tanner.

Wright’s success confirms Tanner’s endeavour. ‘I’m just a kid from Turley who made it out the hood because I had a dream. I had a vision. Now I’m executing that vision and all of this feels right thanks to everyone who has supported me,’ says Wright.

Tovah Tanner reminded me of the African proverb “If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together”. I believe there is a world in which capitalism can help black residents of cities to accumulate the ‘lost’ wealth. Black capitalism can make our cities better for all of us.