In the United States, mass incarceration is a serious problem. It’s given a lot of op-ed coverage, and public safety is often at the core of the dispute. Some opinions argue for shortening sentence lengths and reducing the kinds of crimes that send people to prison, while opponents balk at reforms, believing that America’s system of mass incarceration rightly fulfills the purpose of ensuring safer streets. But neither has given enough thought to parental incarceration.

“Some of our girls are in families with a third legacy of incarceration,” explains Julienne Louis-Anderson, Director of Programming at the non-profit organization Daughters Beyond Incarceration (DBI), as I sit with her over Zoom. Without paying enough attention to the offspring of prisoners the collateral damage in society could be all too high. If your dad has been to college, you might end up going to college as well. But what if one of your parents has been incarcerated?

But it is not too late to break this cycle, although “it is no easy feat,” says Louis-Anderson. Especially in New Orleans, Louisiana.

The state of Louisiana has one of the highest rates of incarceration in the world. Black people make up only 32% of the total population in Louisiana but account for over two-thirds of the prison population. Many of them are parents. Nearly 1 in 7 children in the state of Louisiana experience parental incarceration –four times the national average.

At Angola State Prison in Louisiana (located on a former plantation and named after the homeland of its former slaves), there are prisoners staying for so long that the prison has created an internal volunteer hospice program for the elderly, [and giving us a unique image of convicted murderers caregiving for dying comrades in the process.]

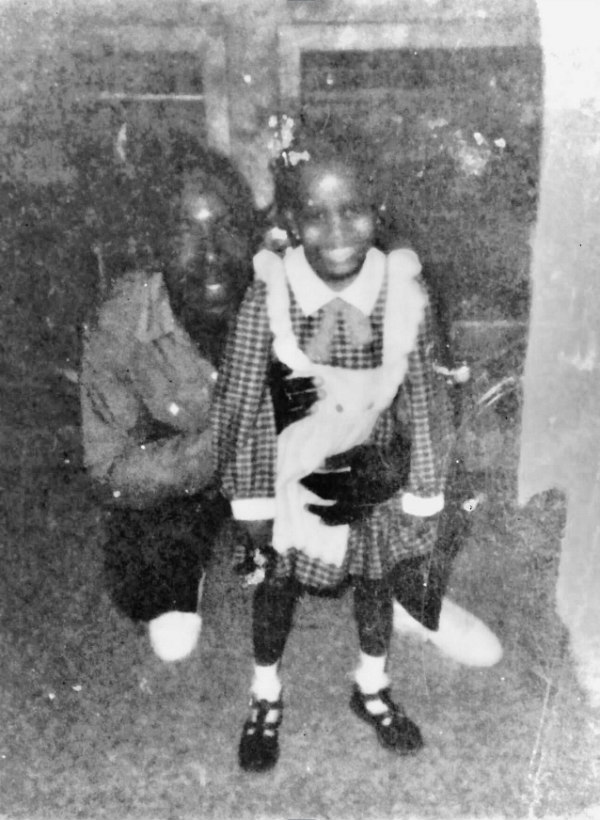

Dominque Jones-Johnson’s father is in this prison, and he is the reason why she founded Daughters Beyond Incarceration (DBI) nearly six years ago, along with her father. He has been incarcerated for the last 41 years, Jones-Johnson’s entire life. She used to visit him as a child and later as a teen, trying to understand why her life was different from her friends’ and to navigate difficult familial relationships. She had to explain her track meets and other accomplishments to her father over the phone and during visitations. If we think about how these experiences have risked, or in some cases severed, the parent/child bond which is so crucial for development, Louis-Anderson tells me, “you realize incarcerations really dehumanizes the parent, but also the child.” And they don’t do society any favors either.

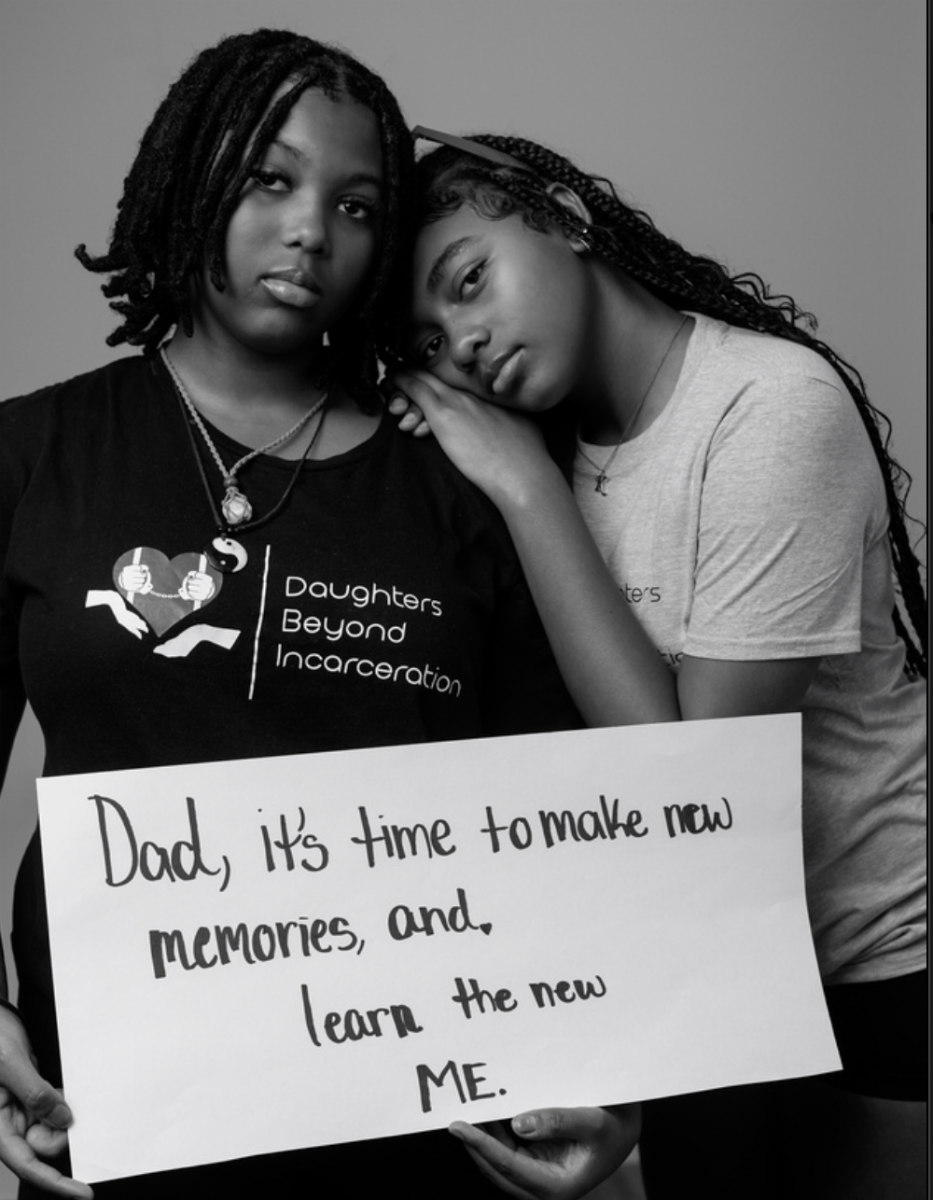

So Dominque Jones-Johnson decided to devote her time to help girls make and keep connections with their incarcerated parents. ‘If I don’t do it, nobody is gonna do it’, Louis-Anderson recalls her saying, ‘because also nobody paid attention to me or cared about my story.’

As she better understood what her father was going through, it allowed her to create a more healing path for both going forward. For instance, when her father would say, ‘I’m gonna call you tomorrow’ and he didn’t, she discovered that it wasn’t because he didn’t want to talk to her, but because of situations out of his control. Maybe a guard had prevented it, or had taken the visitation away, or had even put him in lockdown, or maybe visitation was canceled on his block.

She told Louis-Anderson that she wished she had had somebody to explain all these things to her. “Whether a parent is guilty or has been found guilty, children still have a right to their parents, because we know that allows for psychological safety and all the important markers that children need for development.” Also, it is essential to explain to parents that “just because you are incarcerated doesn’t mean you don’t have the right to attend the graduation of your daughter, for example.”

Louis-Anderson’s father was also incarcerated for a little under two years, beginning when she was five years old. Even though she was very young, she can reflect on the impact that incarceration had on her father. “He was very combative when he first came back home, he was very territorial and very defensive.” As a seven-year-old girl, Louis-Anderson couldn’t understand what was happening, such as why her father couldn’t get a job, why he had to go to the parole office, and what a work-release program meant.

“It would have been very helpful if somebody would have shown me how to connect with him. Because I knew he was very upset about something, but I didn’t know what it was, and so I would just shrink myself because I didn’t want him to get more upset.”

Since DBI started in May 2018, the team has mentored over 70 girls impacted by parental incarceration in New Orleans and the surrounding areas. Four of the five members of the team have a parent who has been incarcerated, so their work is deeply personal. They can competently put themselves in the girls’ position and mentor from their own lived experience – a type of mentorship called the phenomenological approach.

I ask Louis-Anderson how DBI even manages to identify girls to enroll in their programs, given the shame around parental incarceration. In New Orleans, she explains, it is easy to rely on the local communities, that is, on people who know people, but she says DBI also advertises their work at community events and schools. “We make sure we keep the confidentiality of our girls very closely. Even in our facilities, we don’t let other parents in.” And she adds, “this is really for the new girls who are much more shy and they don’t want anybody to know. And that’s valid.” However, over time, the girls begin to move through that level of shame to empowerment. Talking about their experiences lessens their shame. So they talk about their parents being incarcerated, how it has shaped them and how it makes them who they are.

Through being mentored, the girls feel empowered to advocate for themselves at school and in their own personal lives, in friendship or romantic relationships. Often they don’t see positive romantic relationships modeled by their parents, Louis-Anderson tells me, thus the important prevention work in terms of gender-equality so that these – and hopefully in the future many other – girls know “you can be treated how you want to be treated” and build a better future for themselves.

So far all the girls mentored at DBI have graduated from high school. Younger girls have decreased explosive outbursts which result in less suspensions and detentions. The other positive effect of the program, as research also shows, is that when parents have really strong relationships with their children they’re more likely to get parole. There is every prospect of success in providing support during parental incarceration.

But this is not all. Every year DBI chooses five girls for its policymaker program. Every Monday through Thursday after school, these five policy fellows learn from Black professionals including lawyers and community advocates about the legislative, voting, and criminal justice processes. “It’s critical for girls to know what happens from the time their parents are arrested through hearing, to parole, to release and probation.” They go to court houses and to universities, and talk to lawyers – all with the goal of creating their own legislative bills and improving the quality of life for the 94,000 other children with incarcerated parents in Louisiana.

Just last year, the government of the state of Louisiana passed one such bill that permits incarcerated parents at penal or correctional facilities under its jurisdiction to virtually attend the award ceremonies and graduate commencement exercises of their children.

Once a year, during Youth Day at the Capitol, and in collaboration with schools and other organizations around the city, DBI brings young girls to the Louisiana Capitol to face legislators and meet people working in the legislative system. Instead of leaving these professionals to just figure out what children want, the program allows girls to advocate for themselves in front of game-changers and legislators.

“In the US we actually have a lot of people who make policies about children who don’t know any children. They don’t listen to children; they don’t talk to children,” says Louis-Anderson. “When we put policy girls in panels, we might help craft their argument, we might help with the tone and delivery, but they’re speaking from their own experience – telling their own stories. So that adults can start to see things in a different way. The legislators start to understand the power of youth.”

In two weeks Louis-Anderson is going with the girls to Washington DC to speak to their Louisiana State representatives and advocate for their bills. They are moving the needle of parental incarceration (and America’s obsession with mass incarceration) towards true and informed policy making – and in less than 15 years, these girls could be the policymakers themselves.

Follow DBI on Instagram and Julienne Louis-Anderson and Dominque Jones-Johnson on Linked-in for updates on their donation campaigns to support their work.