The best time to visit Sharm El Sheikh is in spring or autumn with an average temperature of 25 degrees. Perfect timing for the COP27. Yet the indoor part of the conference runs on air conditioning as is usual at COPs. One keeps wondering if this ultimate form of climate control, that distorts the reality of climate change, is entirely necessary.

Switching it off in favour of low-tech solutions like open windows or wearing shorts instead of suits, could have been a cool sign on the fight against climate change. Instead we keep alienating ourselves from nature. Sure, bigger plans are on the COP agenda than its AC venues, and we shouldn’t give up technology and return to the caves either, but shouldn’t we recalibrate the simplest things?

This summer, while going through social media during the heatwave, I was struck by a photo of city pavement that illustrated the relative lower temperature of some wild plants growing through the concrete as opposed to the asphalt around them. Over the posted image, Miguel Serrano from Santiago de Compostela, Spain, tweeted, “The stone pavement of the historic centre is boiling hot, but not everywhere. Colonizing “lumpen” plant species are making cities more hospitable. Let’s help them as the allies they are.”

Our obsession with well-manicured urban environments makes it difficult to ally with nature. For reasons that continue to baffle, city administrations remain stubbornly resistant to wild plants on the streets, and are apt to build parks, green roofs and plant trees.

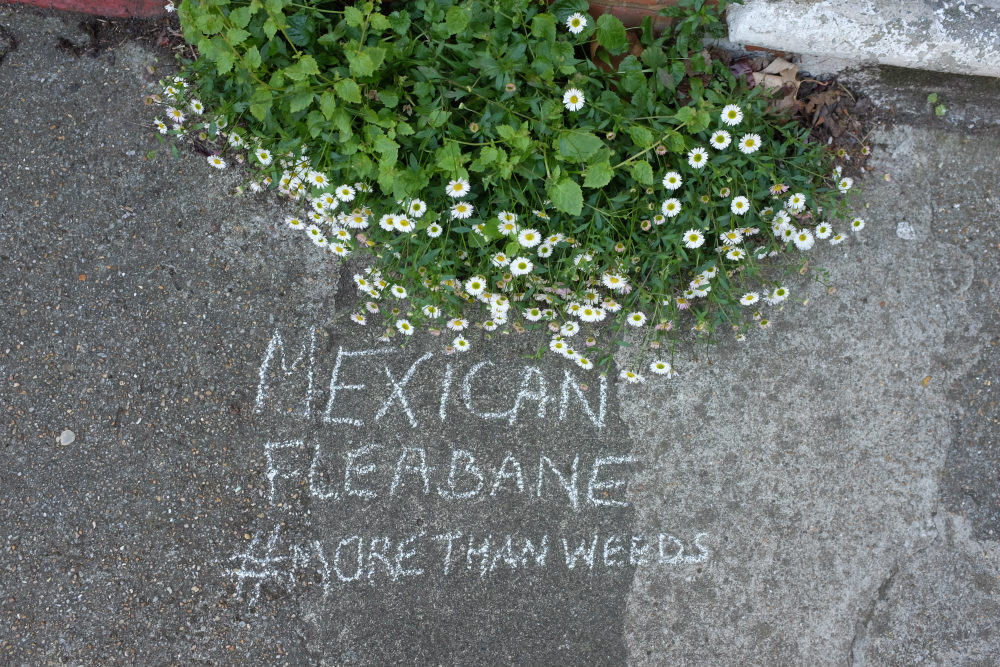

Luckily nature keeps banging on the door, and sliding through concrete. More Than Weeds, a movement born in London, came along to change our perception of urban plants growing on walls, pavement and tree pits, and to re-learn how to live with nature.

“We like imposing [our will on] things; it is in our human psychology,” says Sophie Leguil, the founder of More than Weeds. She is not a psychologist but an experienced botanist who has often discussed urbanism and nature with architects and planners. They often come to the same conclusion: “public spaces feel like they are imposed on us”, including the assumption that unexpected wild plants are not allowed to grow on the streets.

To understand why, let’s rewind history. In a well-researched article, Leguil explains how in Tudor times, weeding was done manually, often by poor women working bending over all-day long to remove unwanted plants between desirable flowers. In the 19th century, particularly with the expansion of cities and paved streets, weeds were seen as unsightly, distracting from the magnificent urban architecture of the century. People started to look at other methods such as chemicals that could reduce the amount of manual labour required.

Some residents are pleased to see nature being allowed to thrive, others are horrified by this “neglect”

The progress of the chemical industry and the postwar aesthetic of a clean and controlled nature lead to the use of weeding chemicals. The discovery and introduction of the even cheaper glyphosate in the 1970s made weeding accessible to everyone; local authorities and domestic gardeners could now wipe all wild plants off the streets.

Inspired by the initiative Sauvages de ma rue (“Wild plants of my street”) created in France in 2001 by the French Natural History Museum and the botanical organisation Telabotanica, Leguil started something rather less scientific and more informal in London in 2019. She began recording urban flora through walks, transcribing it into botanical information with the commonly used names and sharing it on social media.

Her posts went viral. Pictures of wild plants growing on streets around the world kept feeding the hashtash #MoreThanWeeds. Since then More Than Weeds has become rather a movement that has expanded to other UK cities. Somebody from rainy Glasgow shared a sunflower growing between the road, a fence and a rubbish bin. A retired scientist found Nicandra physaloides, better known as Apple of Peru, on the pavement near Tide Mill, Woodbridge, Suffolk.

A resident of Islington, London, in support of a campaign to phase out the use of glyphosate by the Islington council, wrote: “This is what happens when you don’t spray glyphosate: seeds dropped by birds or windblown, germinate, creating mini green patches that lift our hearts and preserve biodiversity.” Emma Cameron shares that “A snapdragon has appeared on pavement by my fence after I asked the glyphosate spray man from West Sussex not to spray there – (behind fence I grow organic veg). It’s not in anyone’s way and looks pretty.“

Unfortunately, not all urban dwellers feel the same way. Leguil tells me over Zoom that some people are afraid of nature, and feel uncomfortable with spontaneous plants growing in unexpected places. Today’s urban residents “may visit parks, tend to a garden or enjoy the presence of street trees, but spontaneous, non-chosen plant growth is seen as “abnormal“, an “eyesore”,” says Leguil.

A current study by the School of Natural Science of the University of Dublin, funded by a European Research Council, is looking into “the societal attitudes to urban wild spaces (novel ecosystems) by working with citizens to study them and generate data on urban ecosystems.” Leguil has been collaborating during data collection and has gathered a lot of evidence on how citizens alter their values and perhaps even their environmental behaviour while engaging with those novel ecosystems.

You can basically wipe out all the insects in our streets, if all the plants are gone. Paradoxically cities continue to preach the importance of planting trees, while using glyphosate that harms them

In addition, Leguil has also been involved in scientific research on how wild plants growing through the concrete can help with drainage on the streets and may help alleviate flood risks. She was also recently in Portugal – a country where glyphosate is still widely used – to spread the #MoreThanWeeds message, talking to local authority representatives about alternative ways to manage and accept urban plants.

In 2014 France passed a law that gave city authorities three to four years to get rid of pesticides and find alternatives. The use of weedkillers became incredibly unpopular in French cities when many dogs died from the consequences of chemical weeding, and the negative impact on human health and biodiversity became clear. “You can basically wipe out all the insects in our streets, if all the plants are gone. Paradoxically cities continue to preach the importance of planting trees, while using glyphosate that harms them,” says Leguil.

Since glyphosate has been banned in public spaces in 2017 in France, she explains, plants have started to grow back along walls, in pavements and gutters. French cities are at the front to rewild cities. An initiative in the city of Nancy allows residents to plant in front of their house, by even removing the concrete on the street, in a strong sign on how the city wants its people to be really involved with nature.

“Some residents are pleased to see nature being allowed to thrive, others are horrified by this “neglect”,” says Leguil. She points out that it is not about letting everything grow out of control but rather changing the perception of people and city councils, and making them accept a less “clean” look. “A lot of times I heard people in the UK complaining why city councils let plants grow if they pay taxes to take care of weeding. We know that this obsession goes back a couple of centuries; in the UK.”

The drive to recreate an image of nature is embedded in the anglo saxon culture, as compared to letting nature grow. If cities are really committed to nature, they would have to stop the use of glyphosate. But since alternatives to chemical weed control are expensive, a change in the current cultural paradigm that streets with spontaneous plants are not dirty, says Leguil, would save money for our cities, and ultimately for taxpayers.

During the Covid lockdown, grass was growing through cobblestones in Rome. Until then, nobody ever realised that nature could come back so quickly. But these rebel plants are also giving us some important clues on issues to fight another aspect of climate change. Recently, The University of Yale published an article on how a common urban edible plant, Purslane (Portulaca oleracea), could hold the key to research on drought-resistant crops.

“Rather than worry about how “untidy” weeds look, perhaps we should start thinking about what they can bring to our lives and reconnect [us] with nature,” says Leguil. When it comes to fighting climate change, any little thing matters. Eventually, leaders will have to wear shorts at COPs.