Church walls and ceilings have been the canvases of painters along centuries. Why not the canvases for 21st century art? Street art at a church in Munich picks up on that role of connecting urban living and spiritual faith. It embodies a kind of sacred activism, which experiments with new ways of reinventing the role that churches play in increasingly secular cities.

On Sundays museums are busier than churches, which are usually only full for Christmas. The rest of the year tourists replace local churchgoers at historic churches and others remain half-empty.

‘The question of what should be the role of the church in the urban community of today keeps me busy all the time’ recognizes Rainer Maria Schiessler. He is an unusual roman-catholic priest in charged of the Sankt Maximilian church in the hip neighbourhood of Glockenbackviertel in Munich.

His methods to attract people closer to faith or spiritual awareness could be described as sacred activism. ‘Belief is not a static thing and you have to adjust to current lifestyles, specially in cities’.

At his services people can bring their beloved puppies. Everyone is welcome.

I am not pretending to have a packed church every Sunday but rather make this great space as opened and inviting as possible to everyone.

‘Here, at the church, we need to find a common language that everybody can live up to’.

Sacred activism aims at reaching a wider audience

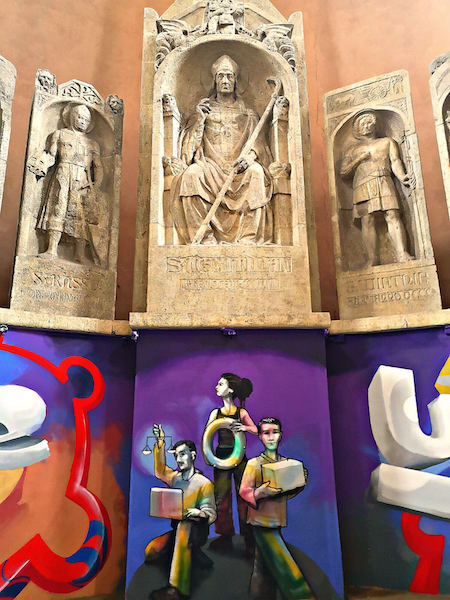

Schiessler and his church helper, Stephan Alof, asked the well-renowned street artist Loomit to spray the alter of their church. This graffiti is not only a piece of contemporary art aimed at reinventing churches in cities of this century. It also contains strong messages to the public. It depicts a modern interpretation of three of the saints in the altar. Whistleblower Edward Snowden represents, for instance, the Truth. The other two saints are Carola Rackete, the German ship captain of Sea-Watch and an ordinary Amazon employee, who could be the holy postman of today.

Schiessler believes that social movements and activism, which have most profoundly changed society, were guided by faith. Faith also serves a social purpose, bringing city dwellers together to mourn, celebrate and to help others. In fact, faith communities have a long history of positively impacting the community with countless initiatives.

But even if religion was once the centre of cities and communities and religious buildings are still erected at city centres, faith is not at the centre of society anymore.

The relationship between religion and cities: Reinventing churches

Is it then that important to drag people to churches in a more secular world? What do citizens expect from a church?

Abandoned churches are slowly being reinvented as secular meeting places in many cities with great innovative ideas. In Canada the citizen collective Espaces d’initiatives founded by Édouard-Julien Blanchet is reviving empty churches as vibrant community hubs. His vision is to transform the church into a space for dialogue, open to anyone who wants to participate in building a better society.

But traditional churches have a mind of their own. They are oasis of peace and quite in the middle of busy and noise-polluted cities. They are indoor public spaces where everyone can just walk in, sit down and relax without being there for a specific reason. Nobody is going to ask you for an explanation.

Instead of reinventing the church as a place, maybe it is time to rethink how to master its allure to people and connect urban living and spiritual awareness again as a unifying factor in a disparate society. Citizens, believers and non-believers, need meeting places in cities to meditate and reconciliate with themselves and others.

At Schiessler’s church every Tuesday around fifty people meet to meditate with music under the main altar of the church where pillars of saints remind of Stonehege. Attendants believe energy concentrates at this very spot.

‘The church truly is about people and ultimately about social cohesion’ says Schiessler. Churches need to find a new language vaguely rebellious to appeal to non-churchgoers, who could find in this space spiritual awareness but didn’t know which door to knock on.

This new language could be expressed through contemporary art like the graffiti at Schiessler’s church, light installations such as a recent one I visited of Phillip Geist’s at a church built in the 13th century or through architecture like the simplicity of the beautiful chapel’s sanctuary in the Archbischop’s Ordinary in Munich or the Bruder-Klaus chapel in the Eifel region in Germany.

Or more radical ideas like starting to change the names of churches to make them more appealing and closer to people or convert them into spaces for interreligious dialogue since other faith communities understandably are requiring a place in society for themselves.

A solution could be the great project still in draft called the ‘House of One’ in Berlin. The idea is to build under one roof a religious place for Protestants, Muslims and Jewish creating a big space for dialogue.

‘I am a big supporter of such a project because only when all religions are bound together, peace can be reached’ explains Schiessler. A space in the city where all faiths could meet would be a precious start.

Life in cities goes fast; therefore keeping spiritual awareness alive is a challenge. Urban dwellers have to be constantly flexible about what to believe and, on that process, some values stay on the way.

The role of these religious structures can’t be underestimated in our urban landscape. Change in society is also guided either by faith or spiritual awareness. The connections between them and the city are undeniable.

From their influence on use of space to attract people to their active role in spiritually supporting people who live in city centres, reinventing churches in cities could address our current needs and even tell us where cities might be headed in the future.