It is not easy to find Samira Benini Allaouat’s compelling work on the net. She has used different pseudonyms for her wide art practice, which includes street art for twenty five years. Her favorite medium is the city and she is used to working anonymously. Her last project to reimagine public lighting in Barcelona, in a sustainable way, has inevitably put her in the spotlight, while her promising solution cannot be seen with the naked eye: geobacters.

A trained trans-disciplinary artist, Benini Allaouat is betting that microbial technology can produce electricity for a sustainable public lighting system and, at the same time, decontaminate the soil from the pollutants which decades of industrialisation by humans have caused on our urban ecosystems.

In a way, she brings to the art practice a new language of science, which interweaves everyday life with the natural world. As a curious thinker, turned researcher, her inquisitive mind led her to experiment with electricity, acoustic sound and physical interfaces with soil when she was at the Hackspace with Hackoustic in London.

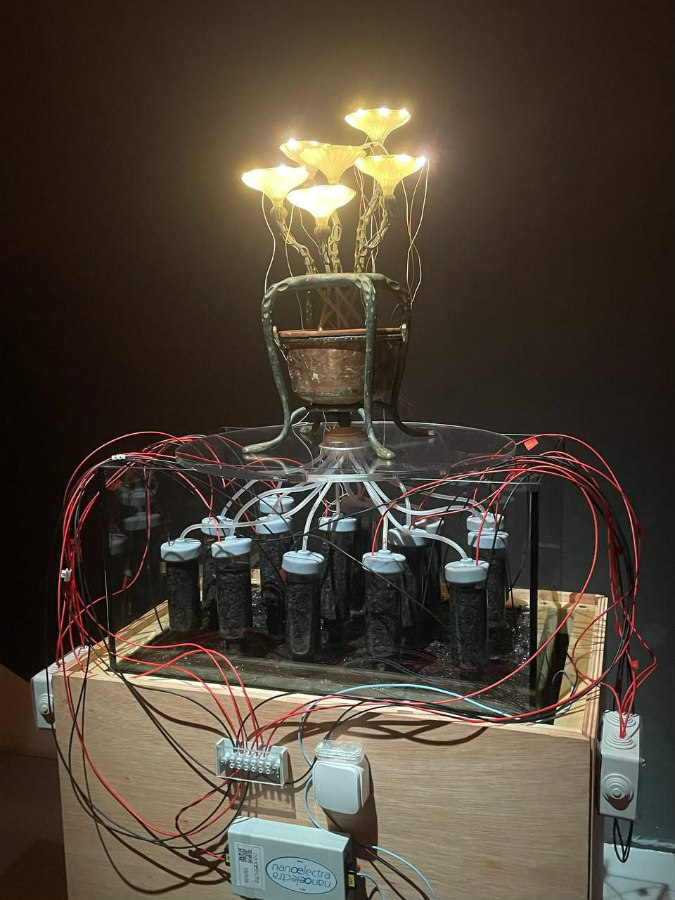

In 2015 she developed the “No Plug Sound Machine”, and it was included at a Tate Modern Museum group exhibition that Hackoustic had put together. A gramophone reproduces an electronic rhythm which benefits from the electricity produced by the chemical reaction of earth batteries, composed of metal electrodes, wired together and buried into the soil of fern plants.

Look closely at the machine and one continues to discover common daily objects, technological items, past and present, and various plants — all intertwined in harmony. Her intention is to question how humanity would start from “zero” in the absence of conventional electricity due to a hypothetical human catastrophe. She challenges the idea of how to keep up with all the advanced technologies and the comforts we have today such as electronic music, but without the supply of energy that we commonly take for granted.

After working on this project, Benini Allaouat recounts an interesting encounter with somebody, originally from Gambia, who told her how people in his country could listen to the radio thanks to a similar composition of pieces of copper and zinc used as electrodes and connected to the soil.

Perhaps with all these experiences in mind, Benini Allaouat began her project Geo-Llum to rethink sustainable public lighting without conventional energy. During her investigation she came across the research group of Derek Lovley, a research professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who discovered geobacters in the Potomac river in Washington in 1993 and have studied them since.

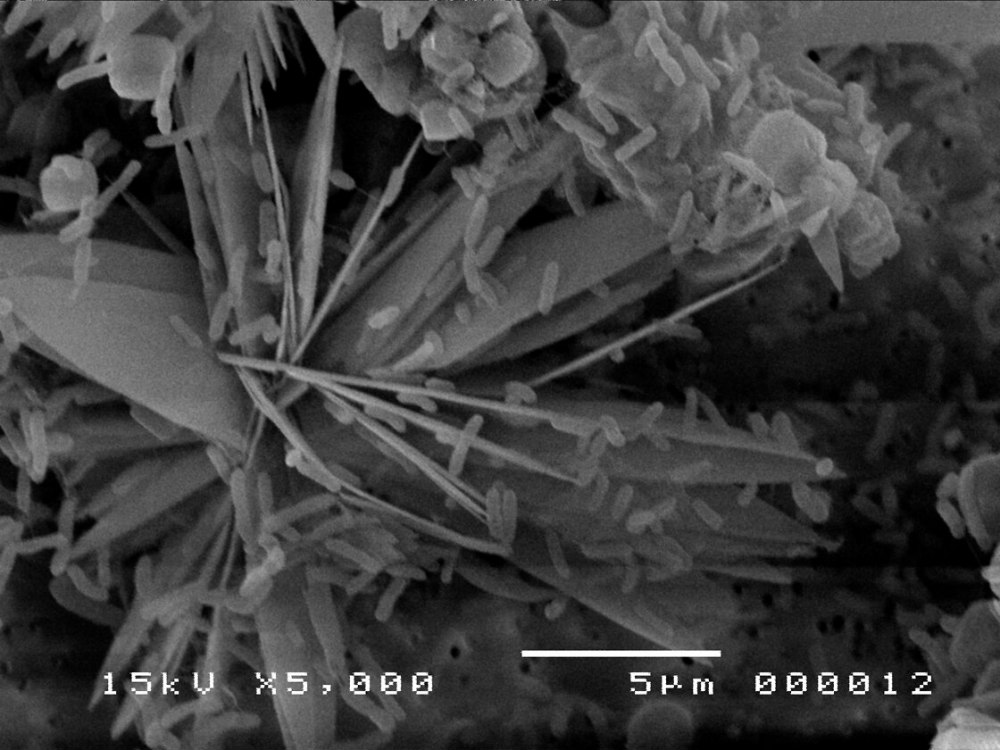

Geobacters are strict anaerobes –microorganisms that are able to, or can only, live in the absence of oxygen– and are members of the Geobacteraceae, a family of Fe(III)-respiring Delta-proteobacteria. They can be found in aquatic sediments and subsurface environments and can anaerobically oxidize aromatic hydrocarbons and remove them from contaminated aquifers.

This permits geobacter species to be used in the development of bioremediation strategies for contaminated environments such as treating contaminated industrial sites and be an important part in anaerobic wastewater digesters. In Spain a group of researchers at the University of Alcalá de Henares in Madrid have been using geobacters to recycle land and purify rice fields by detoxifying them from pesticides, in collaboration with Abraham Esteve Nuñez from Bioe Group and Imdea Agua. After an introduction from Lovley, they have all started to collaborate with Benini Allaouat at Geo-Llum.

According to a paper published by Lovely and his team, geobacters have the capacity to “produce higher current densities than any other known organism in microbial fuel cells and are common colonizers of electrodes harvesting electricity from organic wastes and aquatic sediments.” In other words, explains Benini Allaouat, “this microbe is able to grow on metallic minerals or electrodes, generating electrical energy while eliminating certain pollutants from the soil and water, during its metabolization.”

“These bacteria have a double value: to extract electrons, and that is where we are going to intervene, and to eat the pollution that we have created,” says Benini Allaouat. “With Geo-Llum I found much more than the theme of sustainable electricity for lighting of public spaces, but rather the symbiotic relationship between the artificial and the natural world, focusing on a deeper understanding of the fundamental importance of microorganisms as collaborators in the city, whose soil contamination is largely caused by human activities.” There are so many aspects that need to be considered in the design of Geo-Llum such as the need to store water to keep the soil moistened, and how to efficiently use lighting in cities.

Born in Italy, Benini Allaouat is the daughter of an Italian mother and an Argelian father and was brought up in Paris. “I grew up understanding two cultures, but one culture has predominated over the other. How we live now in the West is thanks to having stepped on other cultures and this affects me. My research is a way to know myself. I try to create peace between these relationships of conflict and oppression.”

Benini Allaouat’s work finds inspiration in technologies from ancient cultures and how things can work with low-tech in places like Africa, where hidden treasures remain on the soil, while others are losing the ground beneath their feet. According to a study by the European Environmental Agency, 60-70 percent of soils in the European Union are degraded as a direct result of unsustainable management. Common contaminants in urban soils include pesticides, petroleum products, radon, asbestos, lead, chromated copper arsenate and creosote.

What is desperately lacking now, Benini Allaouat says, is the interdependence between living beings and disciplines at this moment of the climate emergency. It is difficult to imagine how disciplines such as microbiology, electro-chemistry, bio-electronic engineering, bio design, ecology and science of education can find a connection with art and design for the development of sustainable public lighting but “creativity plays an important role to unite different forces for the coexistence of species, especially in an urban environment.”

This approach firmly convinced a jury to select her project as one of the winners of the Repairing the Present residency program by STARTS, an initiative of the European Commission to foster alliances of technology and artistic practice, funded through various schemes provided by the European Commission. The first prototype of Geo-Llum has been hosted by the CCCB (Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona).

Benini Allaouat is also part of Akasha Hub, a self-managed community of makers and thinkers in Barcelona, where she physically works on the prototype of Geo-Llum, currently in its embryonic stage at a scale of 1:6. So far it has evolved into a beautiful light sculpture made of recycled materials in 3D-modeling (thanks to the collaboration with Miguel Alegre). This art piece is one that urban dwellers would love to find on the streets, standing alone with no plug in sight, which miraculously keeps its lights on with the help of electro-active microorganisms captured in the soil of small transparent containers but invisible to humans.

Right now, this artist and researcher is in the process of looking for funding, which she hopes would provide the resources to develop a prototype in real size to test its effectiveness in collaboration with the Green City Lab at their urban garden Huerta del Clot in Barcelona, where she has already collected soil samples to analyze the contaminants in the garden.

“Geo-Llum could be very useful in the city, but there are certain parameters which must be understood in a trial and error process,” she says. She recognizes that her project is a very new chapter in sustainable public lighting, and for funders, they will have to accept the uncertainty and the risk associated with the project. But, she adds, those obstacles are diminishing, as the social discourse of ecology and sustainability gains more traction.

After Benini Allaouat told me about how she found inspiration in the Baghdad Batteries, I did some research to find out that they are a set of three artifacts which were discovered together at various archeological sites in Iraq: a ceramic pot, a tube of copper, and a rod of iron, and whose origin and purpose remain unclear, and it is very contested. One theory is that they may have formed a voltaic cell, perhaps used for electroplating gold onto silver objects, or some kind of electrotherapy.

But this theory has been strongly opposed by some archeologists who believe that there is absolutely no evidence for electroplating or chemical technology in this region at that time. True or not, Benini Allaouat’s work still evokes the Baghdad batteries; thanks to those geobacters, she would have found a way to illuminate our streets and the excellence of other cultures that have been neglected for so long.