It took awhile to get a hold of Cynthia Híjar. She had changed numbers temporarily in the summer. A security situation forced her to relocate outside of Mexico City. Her only misdeed, to make feminist comedy; her show StandUPerras conjures up women’s rights in Mexico. But she’s not daunted by misogynist comments and threats and has decided to come back home because “the stage is what gives me the most life.”

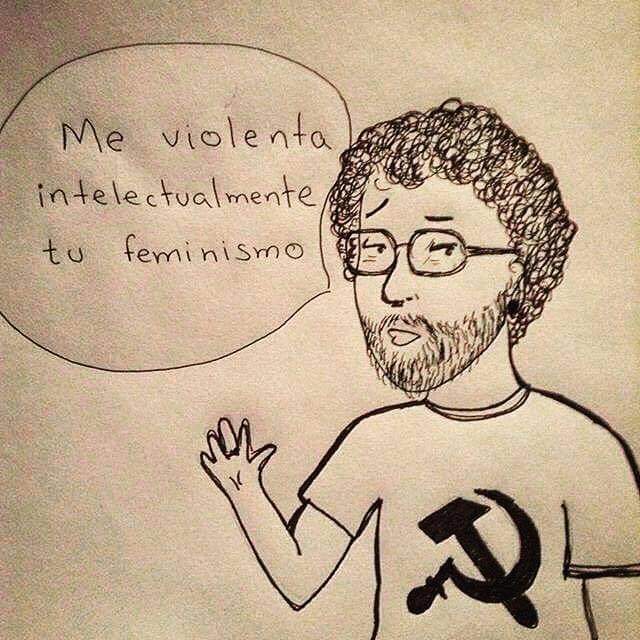

Frankly she hasn’t come this far with her comedy to give up everything easily. All began when she created, together with two friends, the comic character Nacho Progre. The name is a combination of “macho” and a surname that evokes a progressive gaze. He is 33 years old and is a doctor, artist and environmentalist who considers himself a feminist and leftist.

However, in reality, he only supports feminism that does not harm him and he loves to mansplain. Nacho Progre embodies the concept of “progressive machismo” or “neo-machismo” in Mexico that describes men who claim to be progressive towards women’s rights or feminists but who, consciously or unconsciously, replicate machismo on a daily basis. This is how Híjar, over Zoom, describes to me the protagonist of her series of illustrations that won her and her friends over 67,000 followers on Facebook.

But Híjar likes the stage despite the difficulty of a standup career. Not only financially; majoritarily men pursue this profession in Mexico, and it is often loaded with misogynistic jokes embedded in Mexican comedy culture. Amid her success with Nacho Progre, she saw an opportunity to advocate for feminism without giving up the laughter. Her show StandUPerras tears down female stereotypes.

“Being a comedian, and being a woman, people expect you to only make fatphobic jokes,” says Híjar. She has a different idea of good comedy. A TED Talk Híjar gave in 2018 takes me through one of her jokes. She asked the audience to imagine the man who has inspired them most to change the world. Now imagine that you have attended one of his most powerful speeches and at the end somebody reaches up to him and says: “Yes, I like what you say but why are you so angry? You look so handsome when you laugh, I want you crazy, free and shaved! One thing is that you want to change the world, and the other that you don’t shave.” “Can you imagine this?” Híjar asked the audience. “This is what women have to face every time we express ourselves politically….I don’t know why every time I say I’m a feminist people feel a little uncomfortable. It is like feminists are bitter, they think.”

We hear stories from our grandmothers, mothers, aunts, who defended themselves over the years: groping in the street, the subway or at work.

Born in 1988 in Mexico City, Híjar is the daughter of a blue-collar family. She graduated with a Masters in Pedagogy at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Soon she began to work for civil associations, but office life was not something she liked and decided to study contemporary dance at the National Institute of Fine Arts. Since then, Híjar has tried to develop her pedagogical and artistic training as a way to build alternatives for women’s development in Mexico and advocate for their rights. In 2021 she was part of the mentorship program Sister to Sister by the Nobel Women’s Initiative, where the laureates work with emerging feminist leaders and activists.

To get there, it hasn’t been easy. Híjar began performing at independent shows in small places throughout Mexico City, in front of crowds of mainly women and trans men, because she didn’t want to ask male comedians to help her up on stage. “As those spaces were filling up with people, it was evident that there was interest. People wanted to see another type of comedy,” says Híjar.

Edgy jokes about rape, abortion or marginalized communities are making Mexicans look for another national sense of humour and not accept every joke. Especially, when the truth about rates of violence against women in Mexico becomes the elephant in the room. An average of 10 women are murdered each day in the country and around 16,000 rapes were recorded.

There are structures, says Híjar, that make it possible for aggressors to do that without any consequences. Generations of women in Mexico are used to fight against sexual abuse as part of their daily lives. “We hear stories from our grandmothers, mothers, aunts, who defended themselves over the years: groping in the street, the subway or at work.”

Unfortunately violence against women happen everywhere. However, in Mexico they are exacerbated by organised crime, racism, bad governance and corruption, although Híjar is very positive about how the police are paying more attention to women’s complaints. Security also takes centre stage in Híjar’s life. She is often the target of hate speech and threats on social media. To those who believe standup comedy couldn’t fuel femicide violence off the stage, the show StandUPerras has proved otherwise.

Apparently, some Mexican men don’t seem entertained by the capacity of feminists to make other women laugh over the inconsistencies of machismo. They prefer a comedy perpetuated on misogynist jokes. But “whatever your opinion, the things we see on stage and on screen unquestionably shape our views of the world outside,” writes Lilah Raptopoulos, in her well-researched article at the FT, What makes good comedy today?

This author spent the past months exploring the New York comedy scene to find out how it “grapples with the line between provocation and offence.” Her point was that “demands to give marginalised people their due respect are colliding with demands to protect freedom of speech and artistic expression, and it’s playing out most publicly in the world of standup comedy.”

Your work condemns comedians who make rape jokes, you’re not alone in this.

More acutely, this debate is happening in Mexico City where a “macho culture” has surfaced when Híjar took to the stage and hit on an audience willing to draw a line on jokes that humiliated them. In Rabat, Morocco, women are using theater to stimulate unprecedented public debates on female freedom.

But how do you reach the other vast majority of audiences who still stick to traditional comedians and misogynistic jokes? Híjar has taken the show to the so-called anti-monument spaces on the streets during protests for women’s rights where there are no political agendas.

To exemplify how structural the fight for women’s rights is in Mexico, Híjar told me that some places asked them to perform without remuneration, even for the coming International Women’s Day on March 8th. “Firstly it is not right to have women working without pay precisely on that day, and secondly we can put ourselves in a situation of exploitation when we are advocating precisely for the opposite.”

But Híjar has learned to navigate the standup world in Mexico, and she and her team have been asked to do capsules for Comedy Central and internationally. She doesn’t care about all the hate speech and those who say that she is not funny. She found it rather amusing that some men take the time to create a false account to send hate messages. It just reaffirms that her comedy is disrupting minds, and hopefully it might be changing something in favour of women’s rights.

Since Nacho Progre, many men have reached out to thank her for the good laughs, “I laugh but I feel ashamed to be like this at the same time,” one wrote to her. A woman sent her 100 pesos to keep up with the work and not give up. “Your work condemns comedians who make rape jokes, you’re not alone in this.” Híjar, at the end of our conversation, concludes, “I can’t leave.”