It never crossed my mind that a Palestine Museum would exist outside the West Bank, and particularly in the historically pro-Israel U.S. I was immediately captivated by the idea of dislocating Palestinian art and culture, as a license for the museum to answer questions people would otherwise never dare to ask – and perhaps help us reconnect to something that is dislocated within ourselves.

Remarkably, art can help us to live with the horror and absurdity humans sometimes face. It was Nietzsche who said “We have our Arts so we won’t die of Truth.” Nietzsche’s view of the relationship between art and the human experience speaks to the deeper truths that art enables us to access beyond rational thought.

“On the Palestine issue people are mostly entangled with politics,” the founder of the Palestine Museum US, Faisal Saleh, tells me over Zoom. He is in Washington D.C. for meetings. “We want to focus on the arts because we feel they are an effective means to tell the Palestinian story to the world. People have a lot of respect for culture and are more likely to listen and understand through the arts. They speak to people’s hearts.”

In April 2018, The New York Times reported on the opening of this 6,500-square-foot, independent, not-for-profit museum on the outskirts of New Haven. The title of the article “In Suburban Connecticut, the Palestinian Avant-Garde” captures the odd juxtaposition of location and endeavor. But there is a reason (a disturbing one) behind it: “For a Palestinian museum to exist, says Saleh, you have to have what he calls a hardened space,” he says. In other words, if you own the space, as Saleh happened to, nobody can cancel you and evict you because someone thinks “you’re doing anti-Semitic things.”

Saleh’s fixation with ownership can be traced through his family lineage. In 1948, his parents lost everything in Salama, a village which is five kilometers east of Jaffa. Three years later Saleh was born to his refugee parents in the town of Al Birah, near Ramallah — Saleh grew up in the West Bank, attending public school until 1969, before his family emigrated to the United States. He earned his M.B.A. from the University of Connecticut, and eventually became a successful entrepreneur.

Saleh embodies the “American Dream,” and as such, his ambitions with the museum point to much higher goals. The Palestine Museum US should also fill a void at the institutional level that Saleh says exists when it comes to Palestinian art.

He has often reiterated that the museum’s agenda is neither political nor religious. Its exhibitions show evidence of Palestinian life through photography, embroidery, artifacts like stamps and coins, as well as through contemporary art. Inevitably some of the works have been inspired by “the struggle, challenges, injustices, and resilience of a people navigating the brutality of occupation,” says Saleh. And all pieces are produced by an enviable lineup of Palestinian artists. But strikingly, the Palestine Museum US hasn’t drawn much attention from the mainstream media since its opening.

The foresight of this Palestinian-American businessman to showcase and elevate the art of Palestine was never more clear than in the aftermath of October 7th, 2023.

“It’s very important to have such an institution [the museum] because we, Palestinians, are facing attempts to erase us and totally pretend that we never existed. Thus we have to document the existence of Palestine for hundreds of years. Art can show people evidence of that identity,” says Saleh. If Palestinian artists won’t do it, then who will?

***

The Palestine Museum US has already reached an international audience with exhibitions outside the US since the events of last fall. A previous iteration of the exhibition concept titled “From Palestine with Art,” which was originally presented as an official collateral event at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, was restaged at P21 Gallery in London this year.

But this year the Venice Biennale decided that the proposal of the Palestine Museum for an exhibition titled “Foreigners in Their Homeland” could not make the cut. Instead, the show, intended to shed light on life under occupation through contemporary Palestinian art, went ahead as an unofficial collateral event at Venice’s Palazzo Mora. Two weeks ago, I went to Venice to see the exhibition.

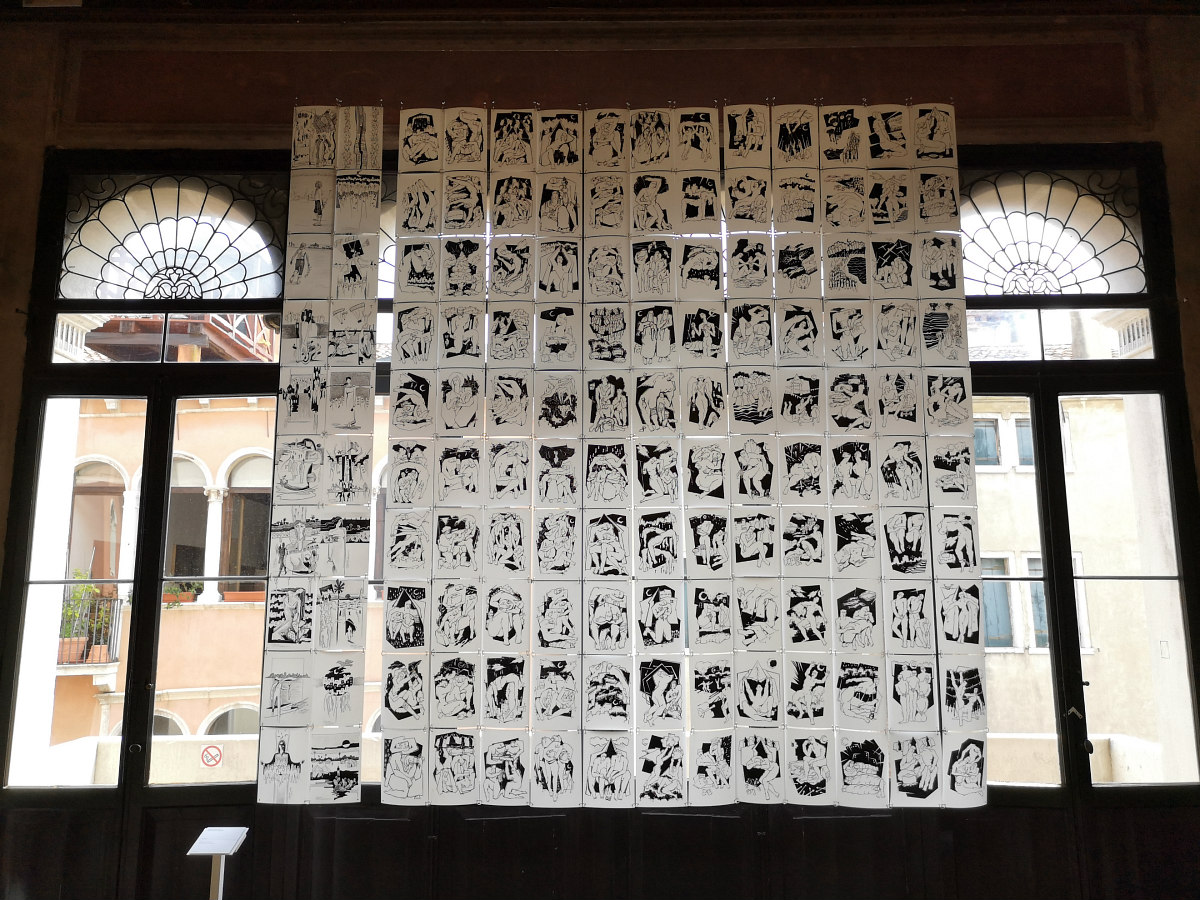

All the artworks are in one sumptuous room filled with light from two beautiful crystal lamps and big windows at the back. In the middle of the windows, like curtains trespassed by natural light, hang 140 black and white sketches by artists Mohammed Alhaj and Maisara Baroud. These pieces of paper, drawn on just with pencil (as artists based in Gaza can’t find other materials), contain tragic scenes of people under continuous shelling in Gaza – rich in details by Alhaj and in a cubist style by Baroud. All together, conceived as a gigantic, singular poster, it constitutes a plea against the barbarism and horror that somehow evokes the masterpiece of Guernica by Picasso.

Without any allusion to specific events, Picasso showed the suffering inflicted upon innocent civilians during the bombing in Guernica in 1937, and the painting became an anti-war symbol, and an embodiment of peace. But, unlike Picasso, AlHaj and Baroud are first-hand witnesses to the disaster in Gaza. Both currently live in a tent with their families. Baroud was a lecturer at Al-Aqsa University’s Fine Arts College, and Alhaj used to teach arts at the Islamic University in Gaza. His studio has been completely destroyed, along with most of his artworks, although a few were thankfully saved in the Palestine Museum US in Connecticut.

The multiple hands painted onto Land Fight by Reem Masri, an artist born in Jerusalem, depicts human’s obsession to grab land, and impose borders, that has been a common denominator of heartbreaking conflicts throughout history until today.

A map placed on the floor in the middle of the room shows the West Bank, including all the checkpoints, restricted areas and Israeli settlements. In a previous exhibition, a map of Palestine was displaced and “All Israel friends came and argued with us about the map on the floor. ‘It says Palestine,’ they say, ‘That’s wrong. It’s Israel.’ We tell them this map was made in 1948, and at that time, it was Palestine. And then they get mad and they go complain to the people who own the building and things like that,” says Saleh.

The somehow joyful street scene and colorful houses in Children of the Camp by Alaa Albaba blurs the fact that Palestinian refugees have been living in “temporary conditions” for 76 years already. For many years they lived in tents; later they were provided with houses made of tin roofs, which were extremely hot inside on sunny days, and disturbingly noisy on rainy ones. Many nights were sleepless. So people started to build their own houses and refugee camps became neighborhood-like areas that don’t grant residents any citizen status.

The exhibition in Venice has brought together young artists with an older generation. Nabil Anani, 83, based in the West Bank, is renowned for his paintings of the Palestine he remembers, as in Blended Landscape where he uses all the Palestinian symbols — the pomegranate, olive tree — in an embroidery-like texture of oil colors on canvas. Samia Halaby, age 87 and based in New York, lent to the exhibition her most recent, Massacre of the Innocents in Gaza, an amalgam of large dots and confusion “where innocents were torn to death.” Halaby was the first woman to hold the position of Associate Professor at the Yale School of Art where she taught for 10 years. And her works made their way into international private and public collections, such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York and Abu Dhabi), the Institut du Monde Arabe (Paris), and the Chicago Art Institute. Her work is also inside the main pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale.

I asked Saleh if young generations of Palestinians feel more detached from their own history. “On the contrary,” he replies immediately. “A long time ago, David Ben-Gurion [the primary national founder of the State of Israel as well as its first prime minister] said about the Palestinians: ‘the old will die, and the young will forget.’ Well, yes, the old died, but the young did not forget. They’re more determined, more attached to their land. The prediction did not really come true at all.”

All the other artists in the exhibition* are determined to depict the hardships that “touch every aspect of Palestinian lives and make them miserable under occupation,” says Saleh.

Although Saleh acknowledged that what was done to the Israelis on October 7th was admittedly horrific and indefensible, he adds it was the result of a siege over Gaza for 16 years, the illegal settlements and military/settlers’ violence on a daily basis, the devastation caused by home demolitions, land confiscations, the unattainable permits that restrict freedom to travel, and the kidnapping of Palestinians by the IDF, putting them in prison in the West Bank — all of this for 76 years of occupation. Eventually, it all blew up, because people can only take so much.”

I asked Saleh his opinion on a two-state solution but he says that is no longer feasible. “That ship has already sailed a long time ago.” And he refers to a short video in the exhibition called A Tale of a Shredded Homeland by Nisreen Zahda that uses 3D animation to illustrate how hundreds of illegal settlements, checkpoints at roads, surveillance cameras, and other movement restrictions have turned the West Bank into very thin shreds since 1880 to the present day.

The only viable solution left, Saleh says, “is one democratic state for everyone that does not leave room for Zionism,” a movement born in Central Europe that envisioned the founding of a future independent Jewish state. And Saleh adds, “Palestinians are not willing to accept living in an Apartheid state anymore, but they are willing to live peacefully in one state with the Israelis, as long as it’s a democratic state where everybody is treated equally. So Zionism will have to go.”

Amid the ongoing carnage in Gaza, in particular the deaths of thousands of children, with many more on the brink of starvation, and the hostages being held by Hamas, I kept reminding myself in Venice that during the Renaissance both Italian and non-Italian city-states employed artists and scientists as diplomats to provide an effective cultural exchange. What if such soft diplomacy could again help to solve the current conflict?

Yemeni researcher and human rights activist Atiaf al-Wazir said in 2019: “Art is not a panacea for every ailment, but it is not irrelevant in times of conflict either. In fact, it’s extremely important, not only because art can document violations. It can break down taboos, but it can also provide relief and an escape. It can inspire and instill hope by making the ugly beautiful.” It is in beauty where we find hope for a shared humanity, and at the very least, art has given Palestinians their irrefutable existence.

*Janan Abdu, Mustafa Al-Hallaj, Rasha Al-Jundi, Alaa Albaba, Mohammed Alhaj, Dalia Ali, Hani Amra, Nabil Anani, Samira Badran, Maisara Baroud, Jacqueline Bejani, Mohammad Bushnaq, Lamis Dajani Shawwa, Jane Frere, Samia Halaby, Ahed Izhiman, Michael Jabareen, Khaled Jarada, Mohamed Khalil, Sari Khoury, Reem Masri, Nameer Qassim, Mohammed Sabaaneh, Khair Alah Salim, Zeinab Shaath, Laila Shawa, Nisreen Zahda.

Update: On May 17, 2025, Saleh opened Europe’s first museum of contemporary Palestinian art in Edinburgh, located at 13a Dundas Street. It offers a permanent space for Palestinian artists to share their stories through art.