The thoughts about death, in general, are disconcerting but not as frightening as thoughts about the apocalypse or mass deaths. Thinking about sharing death with others is enormously scary, at least for me. At four my grandfather said to me, without any prelude, something like the world will explode soon, and all of us will die. It was the first time I experienced that fear. It was much more intense than realizing that someone you love will die, even yourself.

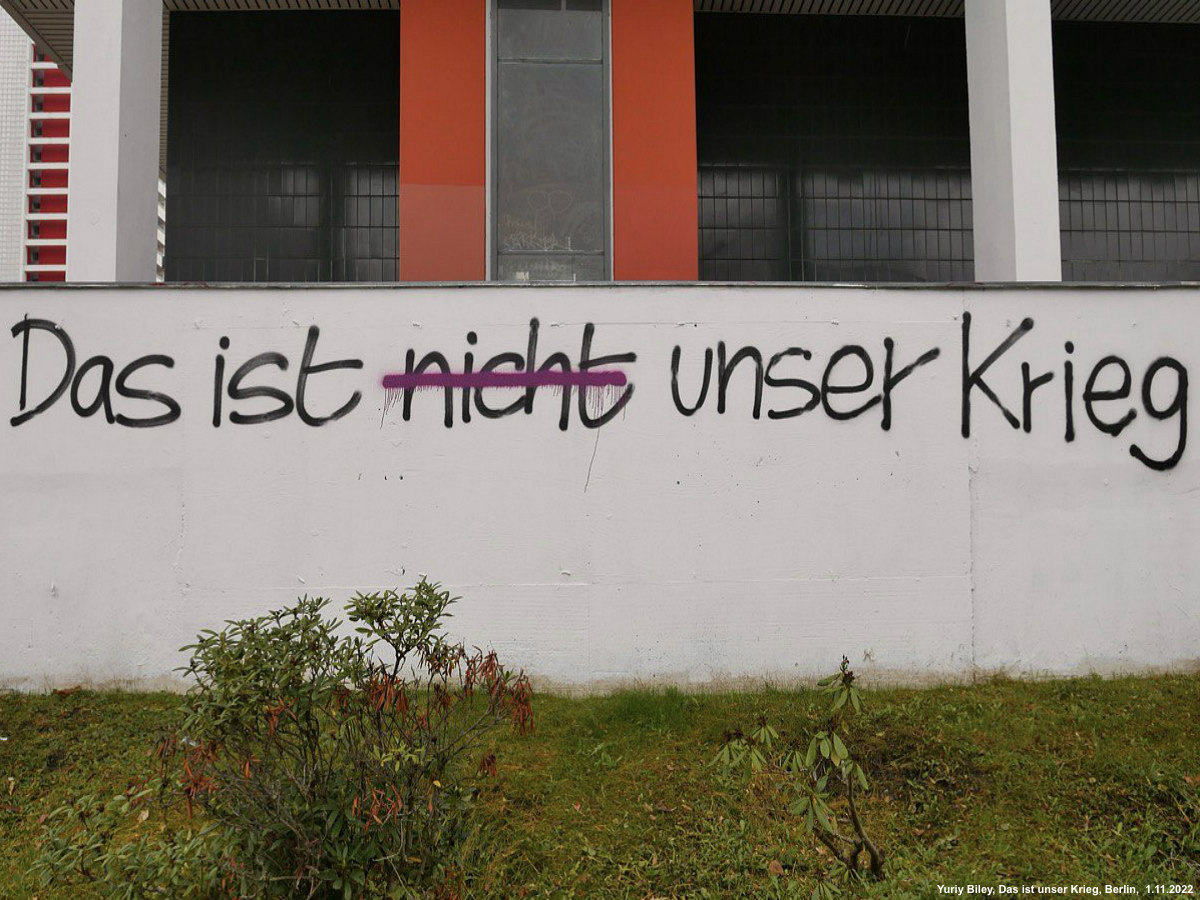

A couple of months ago, graffiti messages were written in a recognisable font stating ‘Das ist nicht unser Krieg’ (eng. ‘This is not our war’) and started to appear on the walls of Berlin regularly. By now: the word ‘nicht’ has been crossed out many times. But this inscription war is still on, and new messages keep reappearing here and there on the walls. It’s unknown if they are a provocation or who’s behind it, but even if it is totally fake and paid for by Russians, it seems to mirror the desire of the masses in a way. It responds to a natural desire to escape empathy and disidentify from the pain of the other.

I left Ukraine right after the full-scale invasion and I haven’t been there for nine months. Even though I read all the news every day and regularly communicate with friends who stayed behind, I feel I am also becoming less empathetic and more disconnected. Perhaps because I am not sharing the physical experiences my friends have.

Amid these reproaching thoughts, I bought a ticket to Kyiv, and there I was at the beginning of December. The whole environment was pretty despairing, yet I felt like everyone was handling the situation relatively well, although there is no comparison to the state of things before the full-scale war. The people I was meeting were a bit less talkative, and only at moments of attacks, I saw the energy I was missing. Everyone trudged to the basement and suddenly I was feeling a little bit more energized because of the adrenalin rush, I believe.

Even though sometimes we didn’t have either water or electricity (due to unexpected shellings), and we were ready to pick up our survival kit at any minute and head to the metro station for several hours, for me, the scariest part of the experience was losing the internet and cellphone connection for 12 hours straight. Then you’re just laying in the darkness in a cold room without heating and you cannot even check what is happening.

Right after arriving in Kyiv, I was sitting in the kitchen with my friend and her 11-year-old daughter, both of whom survived occupation in Bucha. The daughter, Sofia, excitedly counted with her angelic voice the number of corpses she saw on the streets back then. I am struggling while hearing that, yet these memories are going to stay with her forever.

***

In general, I feel that Ukraine is experiencing a very “civilized” war. People are adapting to the situation somehow, and now the noise of electricity generators is haunting you everywhere in Kyiv. People are trying to cheer each other up, and getting a new bank card still takes three minutes even without electricity and internet, which is approximately two weeks faster than in Germany.

Anyway, even in this state of mind, and in-between shellings, Ukrainian artists and art exhibitions in Kyiv have not surrendered to war. Like the Naked Room gallery with the Wartime art archive, and another one in the Mystetskyi Arsenal with a huge exhibition ‘Heart of Earth’. Unfortunately, I cannot say much about these exhibitions, because at the time when I was planning to visit them there was either no electricity or an attack happened. However, I can share some thoughts about the PinchukArtCentre Prize exhibition, where I spent most of my time while in Kyiv.

On December 7th the PinchukArtCentre Prize 2022 exhibition opened in Kyiv (curated by Ksenia Malykh and Oleksandra Pohrebnyak). This show is basically a contest for Ukrainian artists under 35 years old every two years and “provides support for the creation of new artworks” and contributes “to converting Kyiv into one of the world’s leading cultural hubs.” Usually, the jury selects 20 artists among more than 1000 who applied. This time there were only 18 artists because two of them eventually refused to participate. The shortlist of artists was chosen before the full-scale invasion so almost all of the project was somehow modified to the new circumstances.

Overall, the artworks alluded to the current war either in a literal way or indirectly. Some of the artists were dealing with war trauma while presenting an adaptation to the new reality in a more practical sense, while some others presented a more poetic approach to the situation. Two artists, Yuriy Biley and Nikolay Karabinovych, showed deeply personal artworks about their family members in the framework of the migrational discourse. Another topic highlighted in the show was the body in connection to spirituality, or in relation to the acceptance of subconscious desires. Also, artists have become accustomed to visitors sharing the responsibility and care for mutual urban space, and as expected, one of the themes featured in the show was hope.

One of the works directly dealing with empathetic feelings towards the pain of the other is a painting by Krystyna Melnyk created in a personal technique similar to icon painting techniques such as levkas. The painting is so big it barely fits the room, it shows the body of a boy who is covered with the consequences of skin disease. The glow of the skin stands out of the darkness making the space more sacred. Facing the pain in such an atmosphere seems to be very logical: co-suffering and compassion are main Christian virtues. Knowing that the painting consists of an enormous amount of subtle layers of paint, it reveals that the artist spent several months painting it, literally facing the pain throughout that time.

During the preparation of the show, there were many conversations about if it was relevant to present an exhibition and spend assets on artwork production rather than buying needs for the army, for instance. In general, the question about the utility of art in times of war is not a new one. The work, created by Petro Vladimirov and Oleksandra Maiboroda, presented their response to that question in a rather radically practical artistic twist. They collected construction materials used for mounting the previous shows at the PinchukArtCentre and temporarily turned their exhibition space into a storage room. These materials will be handed over by the artists to Ukrainian NGOs for the reconstruction of houses that suffered from Russian armed aggression.

For me, this allegedly very restricted practical gesture can be read as more intimate than it seems from the first glimpse while revealing anxieties connected to placing yourself in the tragedy, being consumed by an inner obligation to be helpful.

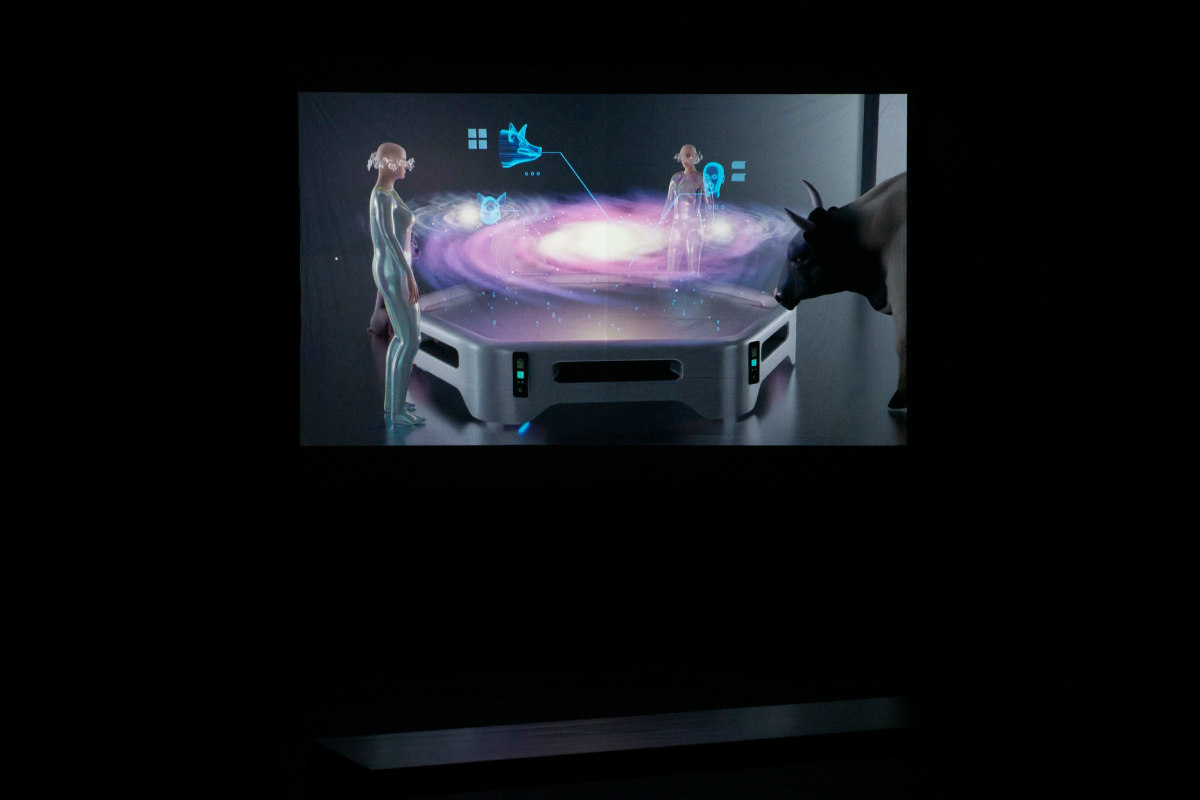

In general, in the projects, there was a tendency of making artworks while building distance from the horrors of the war, trying to find a space for reflection. Some of the artists were escaping reality and were speculating about another utopian world, such as Dana Kavelina and Yuri Yefanov, both of whom presented 3D films about the future. In a way, Yana Bachinska, Oleksandr Sirous, Kateryna Lysovenko, and Maksym Khodak were also emulating an alternate or utopian reality, but all added a bigger grain of criticism.

In particular, the science fiction film by Dana Kavelina sums up the whole show for me. The artist created a concept of the future world ‘without commodity-money relations and unfree labour, where people dedicate themselves to gaining knowledge and pondering the events of the past’. In the film, the citizens of the future decide to resurrect all of those who had died in Russia’s war against Ukraine in order to restore the lost equality of the past and the present. In this world, the true form of equality can only be achieved through equality between the living and the dead. Therefore the scientists of the future revive all of the victims of the war to share the traumas and heal through the collective grief.

In the exposition, right in front of the video projection stands a banner that reads “Resurrection for everyone!”.

In the film, the resurrected victim of the war asks:

“— If part of my memories erased, does it mean I change as well, and I wouldn’t be myself anymore?”

The doctor from the future replies:

“— Yes, and no. We are not our memories. The memory can’t be bigger than the human being or even the same size. The huge amount of you is something that you never think about: the desire for your nails to grow, the talk of the arm and leg cells, the ability or disability to be compassionate towards others. In most cases, we don’t choose the pain which is happening to us, but we can choose not to submit our existence to the pain. We can deprive the obsessive memory of the power over the lifetime.”

***

When my grandfather died, the one I mentioned above, I didn’t feel anything. His world exploded, not mine. Now I think that eventually, it is impossible to be 100% empathetic towards a dead person or a victim of war, you have to live through death yourself to understand that experience fully. For me, it seems like an unsolved dilemma that makes all of the war memorials useless. Either they are trying to talk with statistics or making an immersive show for the visitor. Painful to accept it, but none of these reality shows really work. And it seems like art is the last resort to stir empathy.