The Commons is a paean to public space. Cities blossom in public space; these are the spaces in which societies and their overlapping publics are created. The project joins a tidal wave of social justice action over the last decade – from Occupy and Black Lives Matter to Extinction Rebellion – into the pandemic age, all of which has blown the discourse around the role that public space plays in society wide open. In her public art commission The Commons, artist Gretta Louw questions whether public space as we currently inhabit it reflects our priorities, realities, and values — and how public space could be transformed for social good.

Gretta Louw was born in South Africa in 1981 but grew up in Australia. After completing her studies in Psychology, she lived in Japan and New Zealand before moving to Germany in 2007. Her multi-disciplinary work has been exhibited widely in well-known institutions. She currently lives and works in Germany, where she was commissioned by the City of Munich as part of a series of public artworks displayed across the city to create a public art project relating to the theme of ‘publics’.

I wanted to make a work that is rooted in Munich, where I also live, but speaks more broadly to urban communities internationally, explains Louw.

While her project The Commons was not conceived for the plague, it was adapted and gained new relevance with the emergence of Covid-19. It is an artwork with and for the publics of the pandemic.

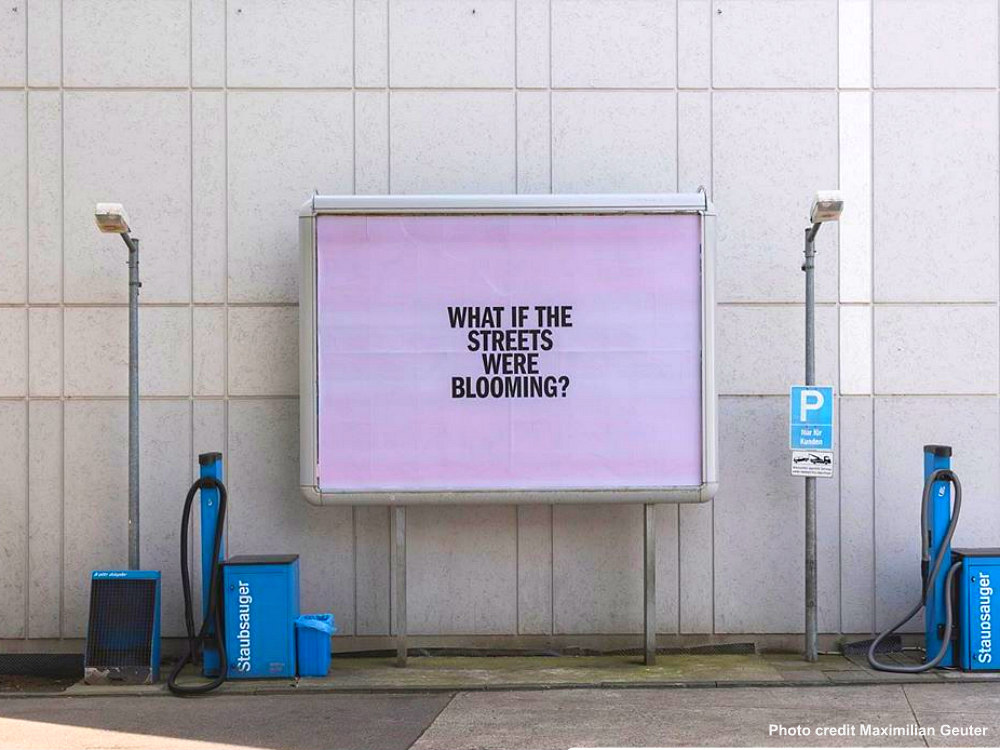

For most Europeans the pandemic lockdown was the first significant interruption to consumption in living memory. Shops, restaurants and cultural venues were closed and the images on billboards stopped being replaced. Into this moment she created a public artwork in the German city of Munich in the form of a series of 17 statements posing as maxims presented in 3 typologies in physical and online settings: posters, online advertisements and social media posts.

“ALL PUBLIC SPACE IS OFFLINE”

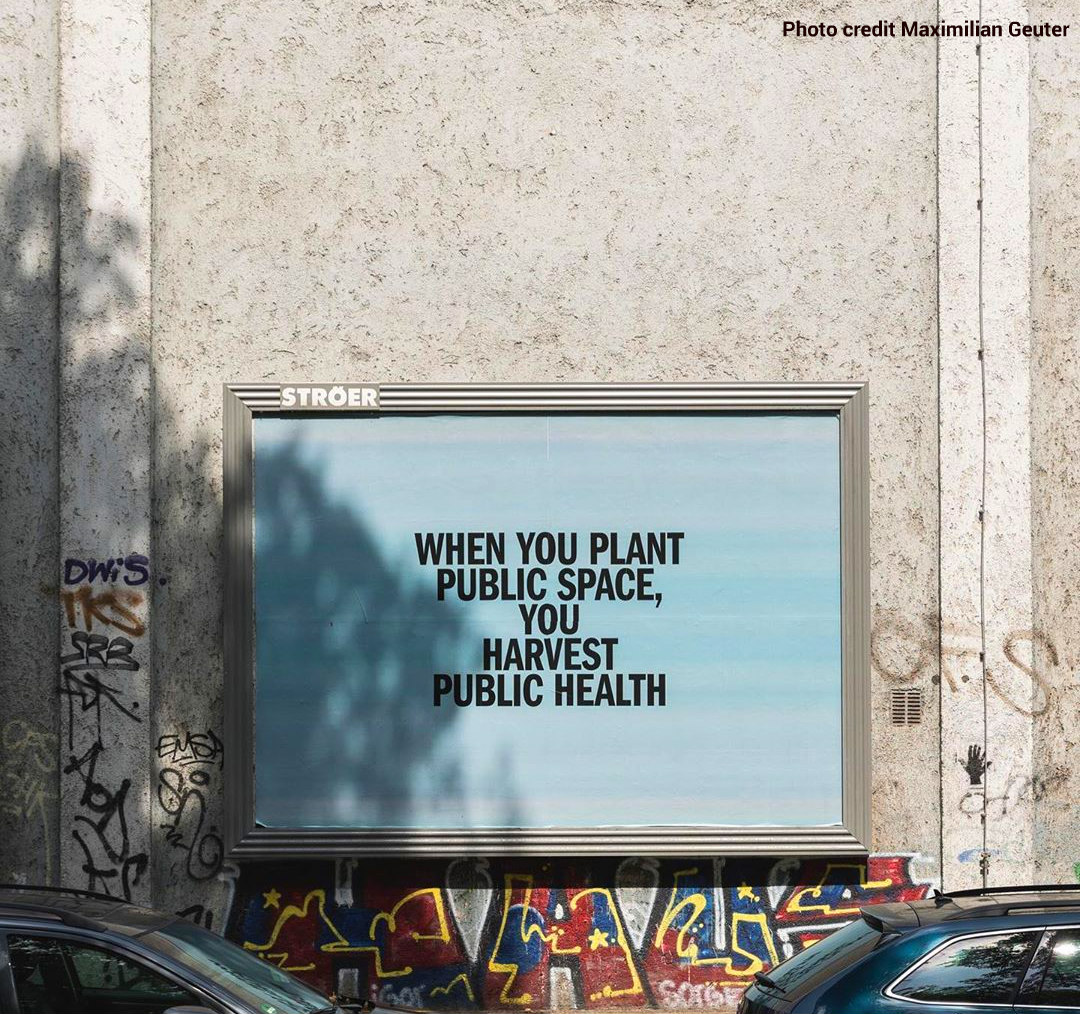

The physical posters are installed on billboards in Munich in places usually reserved for commercial messages – on walls of car-lined streets, pillars, and at busy intersections. Passers-by traveling on foot, by wheelchairs and bicycle are documented pausing to read. Cars speed by. Text on a field of sky blue declares “WHEN YOU PLANT PUBLIC SPACE YOU HARVEST PUBLIC HEALTH”. Recent discourse around access to green space during lockdown has adopted the language of economics. It is argued that we must maintain the health of the masses to reduce the future burden on the treasury. By contrast Louw characterises public space as a living ecology to be cultivated for collective health – as an intrinsic good.

Maxims once functioned as lightweight carriers of insight across distance, time and cultures. Mind worms, viruses even, catchy enough to stick, smart and sage enough to reflect well on the carrier. However 60 years of extractive Neoliberaliberalism and a 25 year global frenzy of distributed online messaging and radical decontextualisation has long-since rinsed all value from our store of centuries-old sayings. We are undergoing an experimental global training programme in the uses and misuses of the “found” utterance, dictum, the quip, and the aphorism.

Since the 1970s, Jenny Holzer’s comedic and combative Truisms taught us to be skeptical about the relationship between the adage and capitalism. Now capitalist state and corporate-sponsored misinformation factories poison the pool of public trust with piranha-like attacks on truth and the promotion of barefaced lies by political leaders. So it is startling to realise that Louw’s posts and posters successfully use this short text format to transmit actual resonant truths.

“ALGORITHMS ARE TALKING ABOUT US BEHIND OUR BACKS”

The online “posters” are distributed as advertising to users of Instagram along with details of the target demographic specified by the artist using the dashboards that any commercial platform user can now access to boost their messages. Some of the pieces advertise the extraordinarily hostile (but widely accepted) conditions created by mechanics of attention in the hegemony of social web. For instance one recites a familiar axiom that “IF THERE ARE ADS YOUR ATTENTION IS FOR SALE”.

However, by also publishing the usually hidden fact that it the post has been targeted to people “aged 13-65, living in Bavaria and interested in online shopping, memes, or viral videos” it garners delightfully reflexive comments from viewers about their role in the cybnernetic loops of an artwork sited in commercial platforms that feel like public space.

Finally social media posts feature photographs of green space in Munich (or the sky above it) alongside a short text in caps, that take on a declamatory tone. One of these pairs an image of baroque gold and purple clouds swirling above a construction crane on the Munich skyline with the exhortation “IMAGINE THE SKY’S A THEATRE AND WE ALL LIE DOWN TO WATCH IT”.

A virtual artwork is created in our minds’ eyes, in which we all lie on our backs in a future park in a new ceremony of nature-cosmic entertainment. The works in The Commons address two dimensions of public space across both physical and online realms. Firstly, public space, as a healthy shared ground of relation to all living beings and secondly, ideally formulated as a commons, as politically necessary to democracy.

Urban poetics: “PUBLIC SPACE TELLS THE TRUTH”

The poetry of this work is germinated in the politics of the commons. It defines public space as a shared resource to be co-governed by its community of users according to their rules and norms, which are formed through patterns of behaviour, presence and use that (as anyone who has spent any time in city parks or squares can tell you) get negotiated in an ad hoc messy way over long periods of time.

The health of our democracies is directly linked to the health of our public spaces as they support the crucial ongoing formation of new publics, who, in turn, attend to diverse collective interests.

Following Jane Bennet* (who follows Rancière and Dewey), publics are political assemblies of human and nonhuman subjects who, by occupying or gathering in space, are able to identify and determine the truth in response to rolling needs and threats and then coordinate in the interests of their collective wellbeing. Truth lives here in the webs of relationships within assembled publics. Post-truth and fake news both bloom when these relational ecologies are interrupted and fascism is the winner.

Genuine public space for social good affords subjects freedom from coercive surveillance as well as the privacy to form a shared sense of reality. Louw’s precisely contextualised posters and advertisements direct our (exhausted, enervated and disoriented) attentions to the ways in which both private ownership and commercialisation impinge on public space.

One online ad inquires “SUPPOSE THE FUTURE WAS MORE THAN JUST NEW WAYS TO SHOP”. In online space, owners (such as Zuckerberg, Brin and Page) effectively determine what can and cannot be said. The algorithms that underpin social media manipulate our psychologies and manufacture insecurities, promoting and hiding messages in a way that manipulates who and what we encounter. The interfaces of Facebook, Instagram et al have created such clever simulations of public space that we have forgotten to expect any public space beyond the marketplace.

The Covid-19 pandemic lockdown has lifted the veil on multiple inequalities – of access to individual and collective freedoms and agency in our societies. Specifically it has exposed the vulnerabilities of an individualistic and competitive social system dependent on centralised, corporate-controlled physical and digital infrastructure. As Louw says “THE LESS PRIVATE SPACE YOU OWN THE MORE PUBLIC SPACE YOU NEED”. Space to live, to gather, to find tranquility, to discover, speak and then act on the truth together.

An idea of “truth to context” emerged in the late-90s amongst net artists who experimented with the participatory media of the world wide web as a sculptural social material. This progressed the principle of “truth to materials” beloved of modernist sculptors and architects, and which held that the form of a work of art should be related to the individual qualities of the material from which it is made. It also had a political inflection, challenging the technocapitalist norms which favoured magical effects and seamless media experiences that promoted a state of trance amongst users. Instead, artworks should wear their codes, wires and mechanisms on their surface – their innate technical qualities not being concealed in any way.

The Commons stimulates us to return to and elaborate on this aesthetic precept by including consideration of relations in the contextual materials of the work. Who is the work for, when and in what circumstances? In doing this it recognises the world (as Robin Wall Kimmerer puts it**) not as an assemblage of objects but as a community of subjects.

By somehow creating statements that hold sway – that remain truthful – even in the 360 degree cubed perspectives of the web Louw reminds us that truth to context might be something to aspire to once again in art and politics as a way to rebuild the publics we need and transform them for social good. They talk about the importance of truth to democracy – and how truth is produced across these spaces.

References

* Jane Bennet, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Duke University Press, 2010, ISBN: 978-0-8223-4633-3

** Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass; Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, Milkweed Editions, 2020, ISBN: 978-1-57131-177-1