As Black Lives Matter keeps the momentum going, inspired Nigerians have peacefully taken to the streets this month, to demand the dissolution of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) to end its unchecked police brutality.

Like in the US, the #EndSARS youth-led movement is also venting the frustration of defenseless citizens over years on uninvestigated and unpunished killings. This reality has created an acute social justice vacuum where little accountability is lawfully demanded from governments and their institutions.

While social and racial justice grass-roots movements keep unfolding in cities, administrations are trying to figure out concrete actions to advance social justice and avoid citizens feeling disenfranchised from their democratic systems. The utter consequence could be future unraveling riots in cities. The incompetence of the system to provide access to justice for all would be a real threat to democracy.

‘It is unfortunate that governments don’t think that people need to vent injustice. No matter how much policies you write, if the local officials do not know how to translate them to communities with tangible actions, the injustice continues at a local level’, explains Tshenolo Tshoaedi.

She is the Executive director of CAOSA, an independent non-profit organization based in Pretoria ensuring that marginalized and vulnerable communities and individuals have easy access to justice, social services and legal support to effectively advance their human rights in South Africa. They unite community-based paralegal offices operating from garages, churches, and schools in townships and low-income neighbourhoods.

South African paralegals, the urban activists democratizing daily life in cities

These local offices – staffed by paralegals based within communities – create spaces of hope for disempowered members of those communities, by supporting them with practical solutions to their own individual problems as well as concerns central to the whole community.

We use the local context to hold the government and its institutions into account. Challenge them by calling upon their commitment to justice, claims Tshoaedi. Advocating for systems that create fair access to legal resources gives the power back to the people.

Due to the fairly economic inequality in South African cities, offices are mainly located in poor settlements like Soweto or new townships built post democracy. In Johannesburg we have advice offices in all five major municipalities, with three or four offices in each municipality. In a month they get requests from 12,500 people regarding equitable access to housing and basic services like water or electricity or they rather help people solve their day to day justice problems, like inheritance or domestic violence.

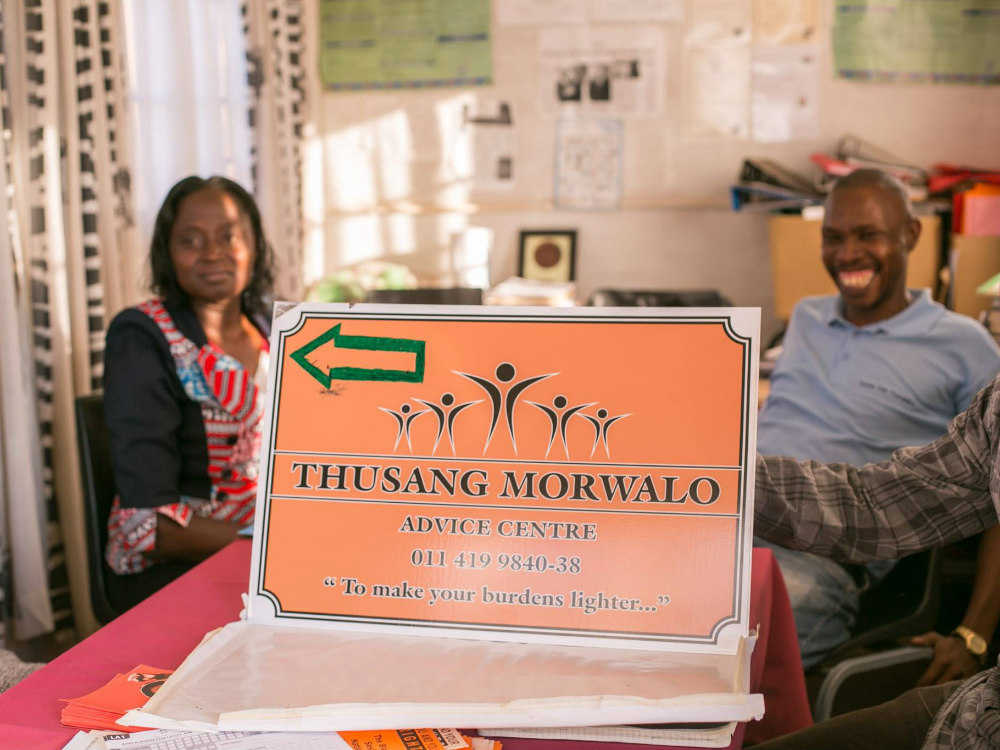

‘Let’s take the example of the Thusang Morwalo paralegal office, a neighbourhood in the West Rand of Johannesburg, where the local priest is one of the board members of the office. It tells you how intertwined these offices are in communities. This particular office operates from a community center where different programs, such as an initiative for women empowerment, share space’, explains Tshoaedi.

Community-based paralegal offices have their roots in the spirit of Nelson Mandela’s advocacy, who was himself a lawyer, and created a network of individuals, or rather pro-bono advisors, who could assit black people in court against the injustices during the apartheid. In addition, the Black Sash, a white women’s resistance organization founded in 1955, established community paralegal offices in areas devastated by political and economic rights violations.

‘Even if these advisors operated in a very informal fashion, they were quite instrumental at the time of the apartheid, they were a doorway to democracy. Some of them were people behind the church or participated in any other form in the civil society. Everybody knew them’.

Nowadays community-based paralegal offices are registered entities offering paralegal aid to demand accountability and justice from the government, thereby ensuring peaceful, just, and inclusive societies based on the rule of law.

How access to justice makes a difference in low-income neighbourhoods

In a country with only 26 years of democratic history, yet the emergence of legal empowerment in South African history could teach other cities how to create real hope for people to thrive in low-income neighbourhoods.

In particular, this innovative approach of a network of community-based paralegal offices provide social and racial justice movements around the world with a real solution to make human rights true to people.

In the US, a country with one of the highest number of lawyers per cápita, the statistics are revealing. According to LSC’s 2017 report Documenting the Justice Gap in America, ‘nearly a million poor people who seek help for civil legal problems are turned away because of the lack of adequate resources. The justice gap represents the difference between the level of civil legal assistance available and the level that is necessary to meet the legal needs of low-income individuals and families’.

In addition, there are also clear implications for people of colour due to the poor health of public defender systems and structural racism. Black people are disproportionately caught up in the criminal justice system and bear the brunt of this unmet need for legal aid because they can’t afford it in the first place.

‘As opposed to the rest of the African countries, when democracy came, South Africa was able to have a peaceful transition to democracy without a civil war. Therefore, the state thought, at that time, that the Constitution would be enough. However, soon they realized that actually these paralegal clinics were very effective to enable the constitution. Because democracy is not necessarily directly related to the problems of people who are marginalized’, claims Tshoaedi.

The fundamental meaning of legal empowerment

Tshenolo Tshoaedi, a young woman and paralegal by profession, is leading CAOSA to progressively develop at the operational level and oversees the measures that regulate the work of the advice offices, representing all in the national agenda. Since they want to keep their independence from the government, they are a non-profit organization funded by donors, who help strengthen a vibrant and healthy civic society in South Africa.

Understandably, funding is a huge concern to keep their fundamental work alive. Putting the power of the law in the hands of disadvantaged people has an enormous potential to ring the alarm on corruption, even at the national level.

Tshoadi explained about the case of an elderly person who claimed that her pension from the state was decreasing over time for no reason. At that time the state had asked a corporation to do the pension reimbursements but some small amounts were deducted from her payment. After further digging they realized that was the case in other people’s pension payments and became a national issue. Black Sash came on board to bring the issue at the constitutional level and it all ended up uncovering a mass fraud against citizens.

A country will never develop if it leaves people behind and inequalities persist, says Tshoaedi.

On 31st October World Cities Day, social movements, civil society and local governments’ organizations are claiming the Right to the City for all. Movements like #BlackLivesMatter and #EndSARS have big expectations on social justice to demand accountability as part of their healing process. ‘Healing is a huge part of what justice brings’, says Tshoadi.

South Africa’s vibrant history of community-based advisor activism has proven to still be quite effective and necessary to hold the government and its institutions into account in today’s world. All is based on the strong belief in the right to legal aid at the local scale.

Making human rights not abstract for those who need social justice the most could give them real hope to thrive, provoking transformational change in cities. And ultimately it delivers democracy.

As for now, and on World Cities Day, to those across the Atlantic, who feel defenseless and advocate for equal access to justice my immediate advice is go out and VOTE.