When you read for the first time about Banu Pekol’s work in the Tatavla neighbourhood in Istanbul it is almost impossible not to think about the museum of innocence in Orhan Pamuk’s novel of the same name. Kemal collected each object related to his beloved Füsun to keep that period of fervent love alive and be at peace with himself. Later Pamuk turned fiction into reality and opened a museum of the same name to evocate everyday life and culture of Istanbul. Banu Pekol’s love affair has rather succumbed to the city’s memorabilia made of uncomfortable, untold stories, in between walls of historic buildings. These are places with stories to tell beyond beautiful architectural enclosures. Brought up secularly, Pekol is a cultural manager and researcher dedicated to peacebuilding through heritage, historic buildings and cultures, with a complex past.

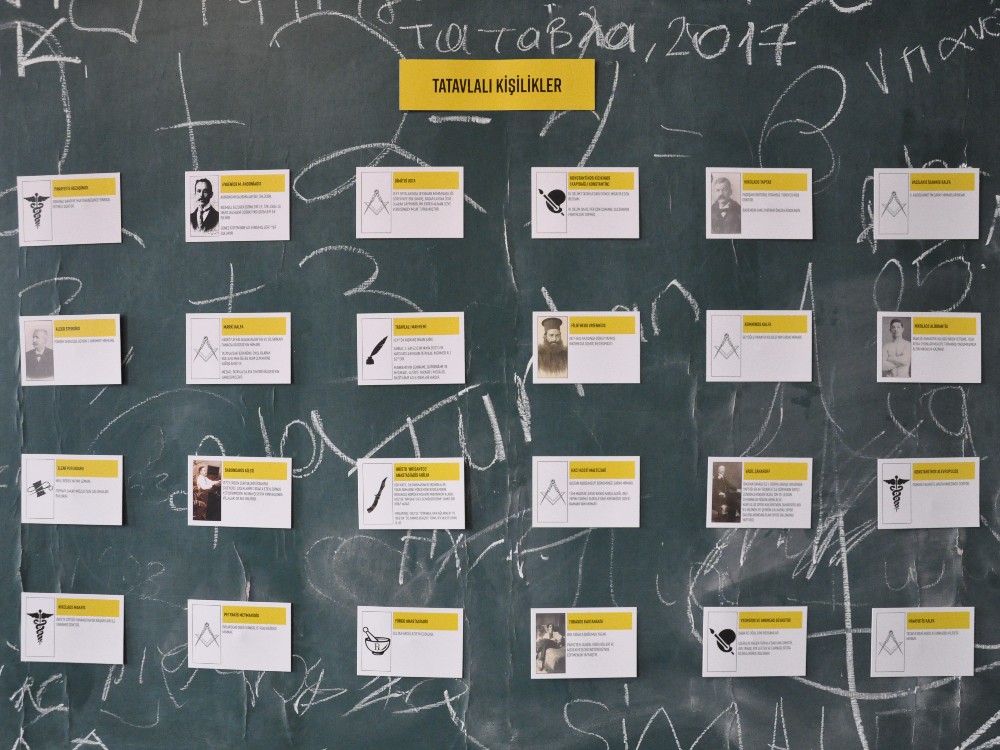

She and team members Cagla Parlak, Mesut Dinler, Tamar Gurdikyan, and a group of students created an archive of memories of Tatavla, today Kurtuluş, an originally Greek/Armenian Christian neighbourhood, with schools, churches, taverns and beautiful houses built in the late 19th-early and 20th centuries, some of which still stand today. They recorded interviews with elderly neighbours on stories from day-to-day life, which helped document buildings and places to track changes in the neighbourhood and portray the diverse urban life of a community almost gone. Many buildings may have disappeared but the transcriptions of those interviews, historic photos, maps and newspaper clippings spoke of a rich social and architectural memory.

The lives of these Istanbulites, who once lived in Tatavla and in other unique neighbourhoods, ended in waves through genocides, drastic governmental measures, pogroms and expulsions during traumatic periods of history. These minority communities were pushed away from their home city, where some had settled in even before the Ottoman empire. With growing nationalism, their traditions got legally banned, security began to be a concern and urban development started to erase ‘old’ buildings.

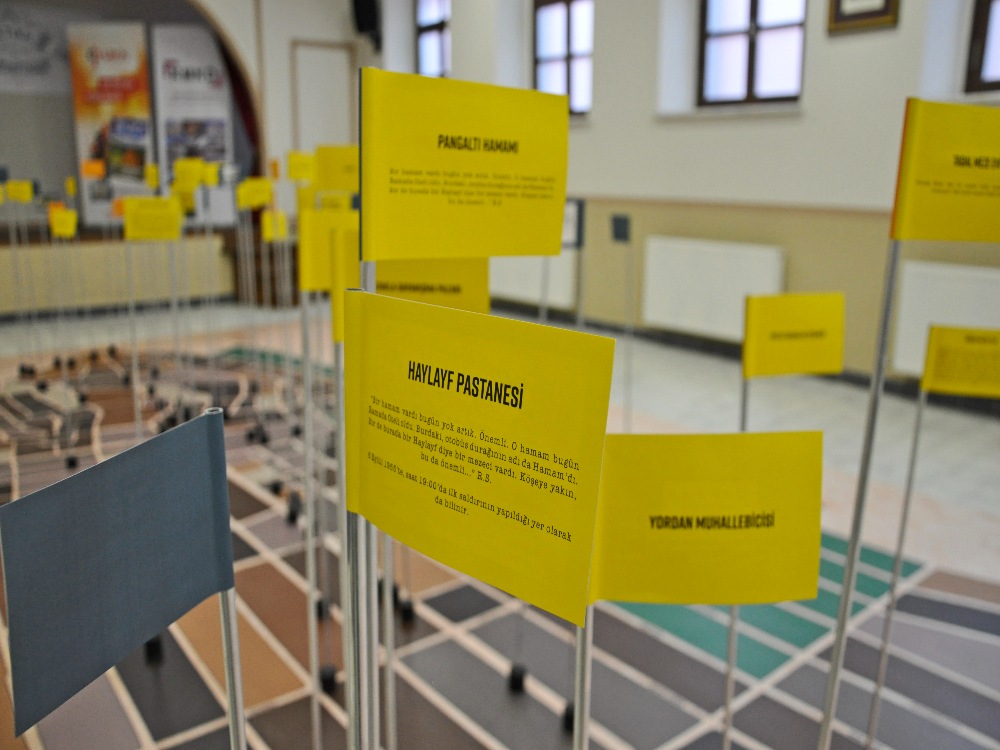

The failure to properly implement holistic historic preservation policies threatens to destroy the remains of Tatavla’s unique heritage. Through oral history work and data from archival research we produced a “map of remembrance” to revive the multicultural, historical memory of the neighbourhood, explains Pekol.

The culmination of the project, an exhibition curated by Pekol in the still standing Kurtuluş Greek Primary School, proved to have a liberating effect on its visitors and a healing effect on the former residents of Tatavla to restore mutual trust and reminded current residents of the richness of cohabitation among communities in Istanbul. Thanks to the support of Actors of Urban Change, a program supporting projects for sustainable urban development through cultural activities by MitOst e.V. and funded by the Robert Bosch Stiftung, the exhibition also travelled to Athens where most of the former residents of Tatavla live today.

It moved some visitors to tears, who realized how little they knew about the history of their neighbourhood and had no idea that Turkey had been so unfair to its former residents. All these little stories in the exhibition, such as the favourite place of previous residents for ‘addisababa’ ice cream cake after school or sharing food recipes with visitors, put humanity on the forefront beyond any predominantly nationalistic narrative. Yet this city is struggling to resist a monoculture society.

By the end of the 80s, Istanbul grew exponentially with immigrants from the countryside, who settled in new neighbourhoods in the periphery, where this kind of multiculturalism never existed, explains Pekol. Due to this form of immigration, any opportunity of exposure to diverse Istanbulites has decreased. In addition, Greek, Armenian, Syriac, Bulgarian Christians, and Jews had either left the country or forced to be much less active in the socioeconomic life of the city.

Today, one can live for years in Istanbul and never get to know a Greek, Jewish or Armenian Istanbulite, explains Pekol.

Istanbul not only did lose a significant part of its multicultural history, which mostly remains in memories of older generations, but also part of its architectural fabric due to overwhelming urban transformation projects in historic neighbourhoods. These transformation projects often negatively affect the city’s built cultural heritage, argues Vivienne Marquart, anthropologist researcher. ‘Turkey’s heritage management system does not oppose urban transformation, but rather it enables the realization of development projects in historic neighbourhoods,’ so Marquart.

Mega projects like the construction of a third Bosphorus Bridge or a railway tunnel under the Bosphorus had little effective opposition until in 2010 a group of professors and students established the Istanbul SOS Platform, supported by prominent Istanbulites such as Orhan Pamuk. Istanbulites realized that the transformation of the built urban environment was rather responding to the desire to expand a homogeneous narrative for the city, which drew them to the point of opposing the government’s plans to demolish the Gezi Park in 2013 and to build a commercial building in its place, the façade of which would be a replica of the Ottoman-era Taksim Military Barracks. Pro-environmental protests to save the trees of Gezi Park turned into a country-wide protest against the infringement of freedom.

Banu Pekol was at those demonstrations and a year later, she joined forces with like-minded friends, to establish a non-governmental platform to act to preserve the multicultural and cultural heritage in Turkey effectively on the local scale. She co-founded the Association for the Protection of Cultural Heritage (KMKD) in 2014 to document and assess cultural heritage that is abandoned, neglected and under risk of destruction. At the time a full-time assistant professor, she dedicated all her extra time to advocate for the recognition and visibility of inclusive cultural heritage and to its transfer to future generations, together with an interdisciplinary team of conservation architects, civil engineers, archaeologists and historians.

One year later, KMKD started the 2-year project of Tatavla through a journey of upheaval in Istanbul, terrorist attacks and an attempted coup. Pekol realized that to make the most impact in her field, she had to work in heritage activism full-time. She left her job as an assistant professor at the University to focus full-time on peacebuilding and human rights through cultural heritage protection. After working full time at KMKD for many years, she was awarded a fellowship at Columbia University on Historical Dialogue and Accountability in 2020. Today she is working at the Berghof Foundation, which is a 50-year-old international institution, specialising in peacebuilding and conflict transformation.

In the case of very polarized countries, such as Turkey, Pekol is a fervent advocate of soft-diplomacy using creative methods to connect people on another level and foster respect for diverse lifestyles. Working in the micro-scale very specifically, defends Pekol, makes people realize that society is an interdependent community. She adds that these activities of solidarity are very important to turn down the hate induced on each other by the government. The protests that were sparked by the government’s attempt to cut down the trees of Gezi Park reflected citizens’ determination to stop the restructuring of public urban spaces through top-down projects which do not respect individual freedoms.

Pekol aims to build the bridge between peacebuilding institutions and cultural heritage institutions because the preservation of difficult cultural memories and truths, as painful as the past can be, is integral for an inclusive dialogue to build trust for a peaceful future.

Cultural heritage institutions have the responsibility to collect daily stories that are very central to the human experience, but are never written down, in order to preserve the past and the present and future peacebuilding. They must document them and keep them very safe, because at some point, in a more democratic future, peacebuilders will need these archives, says Pekol.

The co-founder of The Association for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, Osman Kavala, a Turkish businessperson, rights defender and philanthropist who has been in jail for over 4 years without a conviction. He has supported numerous civil society organizations to mend historical fissures and to bring Turkey closer to its neighbours. The recent support shown by ten European ambassadors in Turkey for his freedom caused an outrage in Turkish politics.

To put it bluntly, laments Pekol, Istanbul now offers more or less a monoculture led by nationalism and religion, which is very difficult to counter without consequences. However, there might be some hope. As Professor Bettany Hughes, an award-winning historian and author writes, whatever monoculture anyone tries to impose on Istanbul, the city will shrug it off. “There have been so many rulers who tried to create the city in their own image. The city always fights back.”