“If there are no more buses, the fire station is not manned, the shelves in the supermarket are no longer restocked and the day care center closes due to a lack of staff,” if this is the case due to unaffordable rents, then “a city as a whole falls into crisis.”

In the February edition of the street magazine BISS in Munich, academic researcher Simone Egger describes how the city could be at the precipice if its housing situation continues in the same way. On the magazine’s cover the title of her article reads Who owns the city?

“The manager then sits in an office that nobody cleans, and the architect, who has to look after his children, can no longer pursue his professional duties.” Underneath every shiny city, there’s a story of many lively voices concentrated in one small space. Egger compels us to hold our governments and ourselves accountable for the right to belong in the city for everyone. “A balanced society is necessary to keep Munich socially and politically healthy,” she writes.

To the very same question Who owns the city? researcher and economic equality campaigner, Christoph Trautvetter, is finding answers in a rather practical way. He wants to get a grip on the facts about ownership structure in cities. The new circumstances could lay the basis for a true public debate on affordable housing and compel the right change in policy.

It might be hard for some people to believe, but not all tenants know who is cashing in the rent every month. Often anonymous companies from Luxembourg and Delaware also appear as property owners. Trautvetter began to navigate this reality when somebody was evicted close to his house causing furore and a journalist asked him for support to trace the owner who was using a similar tax structure.

What started as a very small research project has evolved into a broad study of ownership structure first in Berlin, and then in other cities, supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This wasn’t unusual terrain for Trautvetter. He is a political scientist, public policy expert and one of the members of the Tax Justice Network, where he deals in particular with the topics of money laundering, analyzes ownership structures, illicit financial flows and tax issues.

Amid rent increases of more than 150 percent in the last ten years, tenants in German cities are starting to ask questions about the owners and their business practices. The problem is particularly visible in Berlin, where the pressure of displacement has gone through the roof. While international real estate funds and private investors buy freely in the city, Berliners want answers.

Unfortunately, responses are rather poor. “We had this discussion with the Senate of Berlin (the executive body governing the city of Berlin),” Trautvetter tells me. “We did an official request about ownership structures and they came back with a response that wasn’t helpful at all because it just contained statistics about the company types available in each district but neither the names nor the owners behind them. Until today the senate doesn’t even know who owns more than 3.000 apartments in the city even though the majority of Berliners have voted in favor of a referendum to expropriate those owners.”

The lack of meaningful data

Every European city has a Land Registry – even though registration is not compulsory everywhere. While most European cities make their land registers publicly available, others make accessing the data difficult. In Germany land registers are public but accessible only on a case by case basis and with a “legitimate” interest rather than analyze ownership structure in cities.

To circumvent that, Trautvetter, together with the non-profit for investigative journalism Correctiv and several local media of cities across Germany, started a campaign to gather data from residents in an online survey in 2018. In addition, he used information available from market reports and transaction reports such as Thomas Daily, Immobilien Zeitung, ImmoScout. Once you get a list of company names, you can get further information through their financial reports and from company registers to identify the final owner. But it gets trickier to trace information of private owners.

By not exposing any kind of information on private investors, we blurred the chance to see how undistributed wealth is in this country.

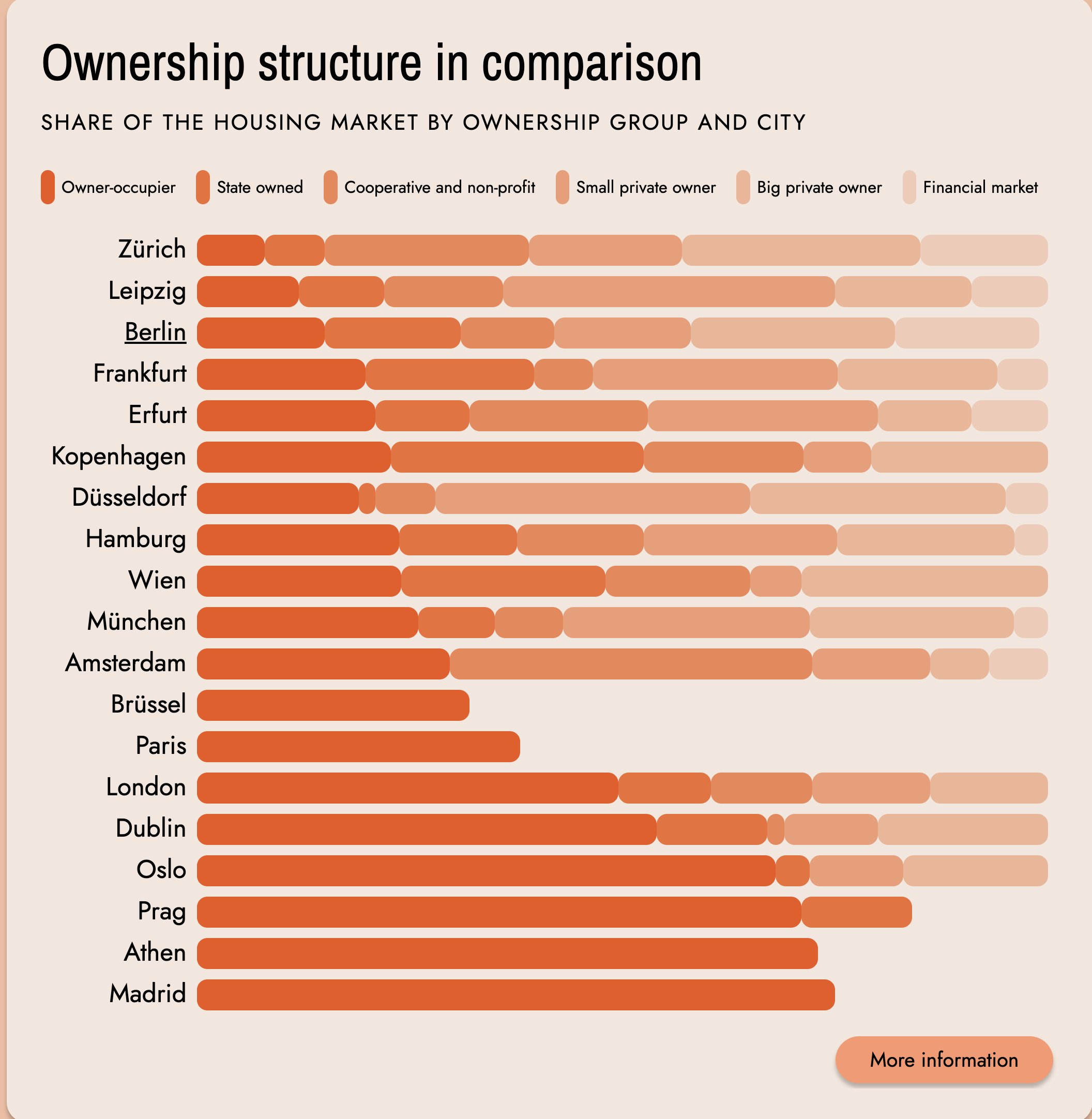

Overall, the study differentiates five types of owners: Owners who are self users; public owners; housing cooperatives and nonprofits; the financial market (Private Equity firms, asset managers and institutional investors); small private investors; and big private investors. It is within the last two groups where the ins and outs of who can afford housing come to the surface.

The official statistics don’t differentiate small from big private investors but the Real Estate lobby wants us to believe that private owners are mainly small size, owning one or two apartments. “But statistics show that this is wrong. Yet 93% of Germans don’t own any rental property and about half the privately owned rental housing belongs to a few thousand people owning whole multi-tenant houses with dozens, hundreds or even thousands of apartments. Among them are many of Germany’s billionaires,” explains Trautvetter. In 1958 a law was passed that allowed people to split a house into apartments and rent them legally. Many owners benefited from this law, he says..

The opaque real estate market in Munich

In Munich a significant number of properties, approximately an astonishing 50% of the total stock in the city, belong precisely to private investors. Yet the city of Munich, according to the research by Correctiv, does not have an overview of who those owners are. The city administration can only give approximate information about the large private owners and only listed a handful of companies.

“We found the response from the city of Munich to be remarkable,” writes Correctiv on their website. In November 2019, the Greens on the Munich City Council sent a written request to the City Planning Officer Elisabeth Merk. They wanted ordinary information about the ownership structure like other cities do. In other words, how many residential units in Munich belong to funds and institutional investors, how many pension funds, insurance companies or private owners. A total of 15 questions. The answer to most of the questions was: “The city of Munich does not have any further information on this”.

The city of Munich was only able to calculate its own stock (a good 70,000 apartments). She named the number of apartments owned by cooperatives (40,000), Catholic churches (6,000) and private owners (200,000).

In 2021 the German newspaper Die Welt officially requested real estate ownership data from all federal states. Some states did provide data, others denied it on the grounds of legitimate interest or alluded to the data privacy law. But that is a peculiar answer, says Trautvetter. Firstly, because the request was limited to institutional investors who don’t have a right to privacy like individuals do.

And secondly, because the same data privacy laws don’t prevent cities in other European countries from making the information on ownership structure public. France even provided a download of the whole register for free last year.

Based on the data provided from some states and municipalities a study by the Ludwig-Maximilins-University in Munich and Trautvetter shows how much anonymity still remains after using all publicly available information to decipher company ownership chains.

Inherited wealth and home ownership

The website Who owns the city? which Trautvetter has put together offers revealing information. With more than 90% of apartments rented, Zurich is Europe’s capital of tenants, followed closely by Leipzig and Berlin. Over the last years, the by far biggest share of European investments from professional, financial market-based investors went to Germany and in particular to Berlin.

Correctiv has revealed an interesting trend. “In Munich, houses owned by communities of heirs often fall into the hands of institutional investors or funds because the heirs cannot afford the inheritance tax. The ownership structure is gradually changing.”

We are calling on the different German states to either change the law or provide the data.

Often Trautvetter was told that the German business model didn’t grow through transparency as in other countries and therefore there is no culture for such a thing. But he continues that, “by not exposing any kind of information on private investors, we blurred the chance to see how undistributed wealth is in this country. The lack of transparency protects power structures that need to be understood.”

“In our study we saw that the main driving factor for housing ownership is mainly investment coming from rich families. Wealth is transmitted and accumulated through generations and, as a matter of course, determines the structure of housing ownership in cities. Without inherited wealth, prospective first-time buyers will face difficulties to access affordable housing. These circumstances differ greatly from city to city depending on how unjust ownership is.

Leipzig, a city in the former Communist East Germany is a good example. Wealth accumulation was non-existent and, as the city opened to the free market, investors grabbed most of the properties before locals could afford to buy a property of their own.

Last week an op-ed article in the Financial Times illustrated “How London’s property market became an inheritocracy,” where residents are forced to abandon plans of home ownership. Even for a 28-year-old vice-principal at an east London school, who grew up in London and went to LSE, home ownership is more like a “dream”. A reality that Trautvetter says has begun to affect German graduates, and not only blue-collar employees. This Londoner and his partner “are now thinking of moving to Germany in pursuit of a better foundation from which to build a life together.” This might not be a good solution.

Over the years Trautvetter’s dedicated work with Who owns the city? has compelled trust among city governments. It demonstrates why it is important to be well-informed on ownership structure in cities to make the right decisions when it comes to policy.

“We are calling on the different German states to either change the law or provide the data,” says Trautvetter. He cites a big progress with the decision by the Ministry of Finance to collect all the 350 registers available in Germany and to be sent to one central place, where 100 people or so will be hired to connect the data and analyze it. This has been particularly accelerated in order to enforce the application of Russian sanctions law on German properties.

Besides, proper data on ownership structures in cities could dismantle some myths, says Trautvetter, like “if you work hard, you can afford to buy a home,” or “we can’t regulate the rental market because the pension of your neighbor (related to the performance of investment funds) depends on those rents.” If politicians know the market better, citizens can obtain information more easily, and journalists can research with fewer obstacles, better are the chances to correct injustices.