Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

Cathedrals are the work of human hands, from the Middle Ages to the present day. Eight hundred years ago, stonemasons, master masons, were builders and designers of these magnificent structures. Today, stonemasons continue their work through restoration projects led by architects, while some cathedrals still maintain ancient stonemasonry workshops beneath their roofs.

Workshops dedicated to preserving monumental buildings, such as the Cologne Cathedral in Germany and the Strasbourg Cathedral in France, continue to uphold the traditions of medieval stonemasons. These workshops focus on the ongoing maintenance of the cathedrals and emphasize the transmission of knowledge from master to apprentice, ensuring the preservation of techniques honed over centuries.

The cathedral located in Freiburg, in the Black Forest, is home to one of Germany’s oldest and most traditional stonemasonry workshops, known as a Münsterbauhütte. Established around 1200, at the start of the Freiburg Minster’s construction, this workshop oversaw the cathedral’s building process until its completion in 1536. Remarkably, it has remained active ever since. UNESCO has recognized it as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage for representing a living tradition of craftsmanship and cultural continuity that dates back to the Middle Ages.

At the head of the stonemason workshop of Freiburg Cathedral is Anne-Christine Brehm, an architect who has immersed herself in this ancient craft. Her research explored the migratory patterns of stonemasons in medieval times and how these movements facilitated the transfer of knowledge, as seen in the architecture and construction technology of Gothic cathedrals across Europe.

“The profession of stonemason has certainly existed for much longer, but I would argue that the stonemason workshops are a distinct Gothic tradition,” Brehm explains. “They originated during the Gothic period in the 13th century when cities gained significant power.” Through trade, urban centers expanded into imperial cities, leading to a new urban society that influenced monumental building projects. France was the epicenter of the Gothic architectural style, spread by itinerant craftsmen who traveled to share their knowledge.

For example, Brehm mentions that in the 15th century, Hans von Cologne journeyed to Burgos, Spain, where he took charge of the cathedral. “These paths illustrate how craftsmen traveled long distances, bringing their expertise with them and adapting it as needed,” she states. The years between 1418 and 1440 were marked by turmoil, including the Hussite Wars and other crises. Wet summers and harsh winters led to crop failures, famine, and widespread epidemics across Europe. During this period, migration surged significantly, with people traveling great distances, particularly in times of hardship.

Brehm has delved into how these migrations affected architecture by examining the account books of the Ulm Minster in Germany. Surprisingly, this 15th-century Late Gothic cathedral maintains detailed records of every individual who worked on the site. These records often include workers’ names, places of origin, duration of stay, and payments received. “It is fascinating to note that stonemasons were highly mobile. A large percentage of them typically stayed at a construction site for only a short time, frequently moving from one project to another,” Brehm explains.

Stonemasons were among the highest-paid craftsmen and also enjoyed special privileges, such as tax exemptions, as cities naturally sought to retain their services. Those who were truly skilled were in demand everywhere. They often oversaw multiple construction sites simultaneously — which was absolutely common in the Late Middle Ages — even across vast distances. A master craftsman not only provided the designs but also created full-scale drawings that stonemasons used for their work under the master’s supervision.

From 15th-century account books, Brehm and other researchers identified some individuals who were highly innovative and had truly shaped a style. For example, they found Hans Niesenberger from Graz, who planned a closely woven net vault in Freiburg. Or stonemasons from Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, whose work was later applied at the Ulm Minster. Or the Ensinger family — Ulrich von Ensingen— influenced by Peter Parler’s Prague architecture, who began with the Ulm Minster tower and planned the octagonal tower in Strasbourg. However, it is challenging to attribute specific construction ideas to individual stonemasons. Knowledge spread rapidly among these craftsmen, and powerful family dynasties often worked for generations, from father to son and grandson, on high-profile construction projects that lasted centuries.

On large construction sites, a master always had a deputy on site — a young, aspiring stonemason — who oversaw meticulous, exceptional planning for constructions that spanned centuries. Evidence of this can be found on the joint surfaces of stones with written numbers from the late Middle Ages, often uncovered by stonemasons in Brehm’s team during the summer when they remove the stones of the cathedral for preparatory work in the winter. Brehm explains that stonemasons encounter difficulties restoring the site in winter, when temperatures drop too low, as the mortar no longer adheres properly and the materials become unusable.

By the 16th century, major cathedral projects largely ceased. As society changed, building needs shifted from large churches to fortresses and castles. Brehm notes that this decline was likely linked to the decreasing power of cities. The Reformation also had an impact, as churches were no longer uniformly Catholic, and Martin Luther’s opposition to indulgences — which had funded many construction projects — resulted in a loss of financial support. Consequently, many significant church-building projects came to a halt, leaving cathedrals like those in Cologne and Ulm unfinished. It wasn’t until the 19th century, with the rise of Neo-Gothic architecture, that there was renewed interest in completing these structures, leading to the revival of cathedral workshops.

Recommended Read: If Churches Are Repurposed, as in Housing, Who Should Be the Beneficiary?

In contrast, the Freiburg Cathedral never had its stonemason workshop discontinued. Its striking architectural ornamentation, with the little turrets and oriels with statues inside, is an incredibly delicate structure that requires constant maintenance. Stone craftsmanship is embedded throughout the building. Brehm states, “This is why stonemasons have undoubtedly been working on the Freiburg Cathedral for centuries — continuous upkeep was essential.”

In other Gothic cathedrals without active workshops, maintenance strategies differ. Brehm highlights large projects where entire buildings are scaffolded for repairs. “It’s a truly remarkable organizational feat and impressive sheer amount of manpower,” says Brehm. “In contrast, ours is more of a small-scale, piecemeal approach. We have a smaller team of 15 people who work continuously, bit by bit, year by year.”

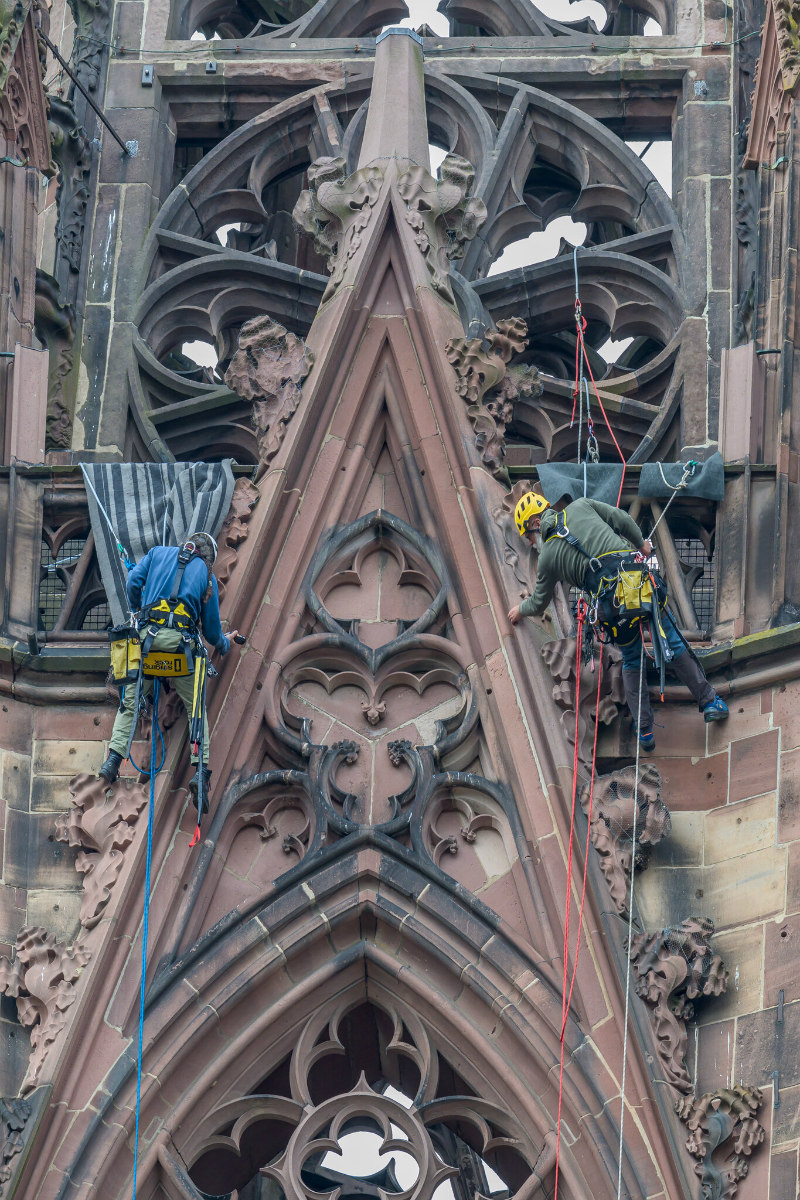

Once a year, Brehm and her team conduct annual safety inspections. “Today our stonemasons climb to parts that aren’t accessible by cherry pickers, like the spire,” she explains. Some of the stonemasons have received industrial climbing training, but since they only climb once a year, they regularly require refresher courses. Professional industrial climbers also accompany and supervise the stonemasons, who know precisely what to watch out for and which types of damage are problematic.

“They examine almost every stone — checking for loose sections, damage, and any potential hazards,” Brehm says. “Then, we take immediate measures to secure everything.” Their standard method involves wrapping stones in wire mesh so that if something becomes loose, it lands inside the mesh rather than on the cathedral square where people walk. “In addition to these annual inspections, our on-site foreman walks the building every week. He follows a specific route; Gothic buildings have walkways along the roofs and windows designed for inspection. I find that fascinating because it allows regular access to the weaker points,” Brehm reveals.

Every September, the Cathedral Master Builders’ Conference gathers architects involved in large restoration projects and those managing cathedral workshops. “We have excellent exchanges within the German-speaking world and with places close to us like Strasbourg,” Brehm notes. However, exchanging experiences with other countries can be more challenging. EU regulations complicate matters. “We have contact with climbers from the Strasbourg Cathedral, but they aren’t permitted to climb with us due to insurance regulations. Meanwhile, the deputy master mason from Cologne Cathedral has climbed with us, and there’s a valuable exchange with his stonemason workshop where we learn from one another every time.”

Every cathedral has its own unique characteristics, and each building uses slightly different materials. The special aspect of stonemason workshops is that they are intimately familiar with the weak points of their buildings and how to prevent issues from arising. They develop their own mortar mixes, specifically formulated for their buildings to ensure compatibility with the materials. Stonemason workshops also source their stones from particular places — the Freiburg Cathedral has a unique shade of red that is currently out of fashion, causing quarry owners to question whether they should supply it. They must ensure they have the capacity to meet that particular demand.

The Counts of Freiburg founded the cathedral in the 13th century, and donations from the citizens financed its construction, since it was initially a parish church; it became a bishop’s seat only in the 19th century. People bequeathed their houses to the construction organization as part of their estates, which were then rented out to fund the cathedral. Furthermore, the best garment after someone’s death — clothing was incredibly valuable back then — was donated to the cathedral organization for sale and to help with maintenance. This practice wasn’t unique to Freiburg but rather a common financing model. Additionally, the quarry from which the stones originated belonged to Sophie von Keppenbach, who ensured the right stones were available for the cathedral organization.

Recommended Read: The True – Yet Discreet – Love That Preserves Florence

Eventually, the city took over the cathedral’s construction, and representatives from the city council acted as building supervisors, overseeing its organization, scrutinizing contracts, and monitoring finances. However, in the 19th century, as Brehm explains, chaos ensued due to Napoleonic rule. The city ceased funding the cathedral, and responsibility shifted to the church until funds for essential construction work were no longer available, prompting the citizens to step in to care for their cathedral.

Since 1890, the nonprofit association Freiburger Münsterbauverein has operated the cathedral stonemason workshop in Freiburg, currently led by Brehm until April this year. Two-thirds of the funding for the cathedral workshop comes from donations and bequests of more than 4,700 members. The remainder comes from grants from the state of Baden-Württemberg’s historic preservation fund, as well as funds from the church and the city. “Fortunately, some people name us as their heirs and leave us their assets. That really helps us ensure the preservation of the cathedral,” says Brehm with a smile.

Every year, her team at the cathedral workshop hires three stonemason apprentices to pass on their knowledge. “This year, we have three women,” she says, noting that there is increasing interest among women in the ancient craftsmanship of stonemasonry. Although cathedrals are built to last forever, and stonemason workshops like Freiburg’s have stood for 800 years, they can still adapt to modern times.