Every Thursday something is brewing at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona (MACBA), Spain. Activists, neighbors and ordinary citizens meet up at the MACBA’s kitchen to share, between stoves and pots, knowledge and experiences around cooking. Born six years ago, ‘la cuina del MACBA’ is closely linked to agroecology, a social movement, a science and a way of consuming and producing that takes into account the limits of this planet.

(Read here in Spanish)

Led by Marina Monsonís, with the production support of Yolanda Nicolás, this kitchen “hacks” spreading food desires, like the insatiable avocado lust, and turns them into sustainable mouth-watering alternatives. While the kitchen is an everyday space where apparently unimportant things happen, ‘la cuina del MACBA’ creates food archetypes that consider the end of fossil energies, the depletion of resources, climate change, food sovereignty, and our health.

I met Monsonís two weeks ago during the URBANBATfest in Bilbao, in the Basque Country region in Spain. Rather than a festival, URBANBATfest is a laboratory for research, learning, experimentation and collective creation that promotes urban innovation processes. Monsonís is an artist, a social justice activist, a writer, who speaks openly about her dyslexia, and the daughter of a docker and the granddaughter of five generations of fishermen in danger of extinction in the neighborhood of Barceloneta.

On the fourth day of the festival, Monsonís tells the audience that she works within arts, politics, food and ecologism, always with a social justice perspective, since 2004. As she shows us in her brilliant, bracingly honest new book La Cocina Situada illustrated by Carla Boserman, we can easily understand the complexity of the current food system, and even challenge it unconsciously, by going through old recipes, tools and traditions in cooking. “There is no science or academic material, even though there are scientific activists such as food anthropologists, agroecologists, and journalists with a gender perspective, who collaborate with their knowledge in the book,” explains Monsonís.

The book contains mainly popular knowledge from our grandmothers, fishermen, shepherds, community kitchens, and different activist antiracist collectives that fight for social and climate justice. “I think we should take much more attention to the popular knowledge in the polycrisis we are experiencing, because we can find very basic forms of resilience,” she beams.

People smile at each other at her book presentation when they learn that any woman could make yogurt from a ‘bifidobacterium bifidum’ from her vaginal flora. Or explain that ‘chimichurri’ sauce – used to season any meal – is an olive oil-based mixture of species, onions’ remains, and any other leftovers about to expire.

Five days later Monsonís tells me over Zoom that agroecology is a holistic approach closely linked to the city. “When we talk about agroecology activism, people think it has nothing to do with the urban environment, but actually it is the opposite. The city is everything because it influences the entire food system. It is troubling that we try to separate the two,” says Monsonís. And she adds, “Yet cities live off the fertile lands and the sea. The city without the farming land does not survive.”

Supplying food to cities involves an effort of colossal proportions. This effort is the world’s greatest cause of environmental destruction. “However, in the West, very few of us are fully aware of this process,” says Gorka Rodríguez Olea, director of URBANBATfest. “Food arrives on our plates seemingly by magic, and we rarely stop to consider how it got to us.”

Ingredients

There is a resistance to admit cities’ disturbing truth: Eating anytime, anywhere has created a global dependency with a carbon footprint estimated at around 30% of the total global carbon emissions (including farming, livestock and energy). URBANBATfest provides additional data about this food supply behemoth. In the UK food travels 30,000 million kilometers before it reaches the plate yearly (equal to circling the planet 750,000 times). Deforestation in Brazil to grow food means logging twice as much as the size of the Basque Country region yearly. Not to mention the loss of biodiversity due to the use of pesticides.

And the list continues. The primary sector, food production, uses 70% of the world’s drinking water. Eurostat roughly estimates that around 10% of food made available to EU consumers (at retail, food services and households) may be wasted.

“Farming is the one topic we are least prepared to talk about. We criticize urban sprawl, but farming sprawls across thirty times as much land,” writes George Monbiot in his book Regenesis. It deserves special attention that this year’s edition of URBANBATfest has risked the participation of the event to bravely create a space of reflection on how the way cities feed residents has shaped their own design and development, precisely in the city of Bilbao, where gastronomy and excellence in culinary practices are at the heart of a region, and where, with the exception of Kyoto in Japan, there is a greater concentration of Michelin-star restaurants per square kilometer.

“The culinary component was an obvious trigger for the festival,” says Rodríguez Olea. “But the festival has been truly inspired by two books by architect and researcher Carolyn Steel.” In her book Hungry Cities, she argues that cities were originally settled on fertile land: ‘just like people, cities are what they eat.’ “A simple and at the same time profound statement that entails assuming to what extent the development of cities is inseparable from the way in which we, its inhabitants, feed ourselves.” In its sequel book, Sitopia, food takes center stage, from our cultural norms to the interconnectivity with local economies, global geopolitics and ecology, and asks what we can do with this knowledge in order to lead better lives.

Drawing on the astonishing composition of collective knowledge at the MACBA’s kitchen, Monsonís reveals how their review of traditions, understanding what adapts tactically to each context and what resists changes, could create diverse and territorialized responses to the crisis. “In short, we take advantage of the wisdom contained in the depths of each recipe,” says Monsonís. Both in fishing and in other matters of food, she considers that the visible figures of the kitchen “have promoted a cuisine that is disconnected from the territories.”

Gathering the tools

“I am aware that my voice is a drop in the ocean of a failed food system, yet micro activism and knowledge have the power to change things from below, while we also need systemic changes,” explains Monsonís. “When we create tension, cracks open to generate creativity and find alternatives that allow us to imagine another possible future.” The MACBA, in its role as an art museum, has put creativity at the service of transforming some dynamics in the current eco-social crisis, it can “act as a speaker, it is a space for tactical and strategic validation that legitimizes our work to yield some change.” “But it’s a tense situation to work in the museum as it represents a lot of violence in the neighborhood because it’s been a symbol of gentrification. Certainly, the right to the city and to a healthy and sustainable food system should be for all and should go hand in hand. The museum’s kitchen is working in this direction as much as it can in favor of the neighbors.”

I tell Monsonís that with all that has been going on at COP28, it’s easy for people to forget that everyday activism is happening all over the world. Monsonís regularly meets the people who are unlocking modest initiatives and methods where she takes part; from community kitchens and cooking workshops in LaFundició; through agroecology consumer cooperatives such as Kerasbuti, liberating the land around the airport to grow vegetables in the outskirts of Barcelona; to the pioneering menus based on agroecology at schools in Barcelona. The latter changes the way children eat, and in public schools, it is an inclusive way to promote healthy food while it supports local farming. There is also Eixarcolant, a popular project with more than 26 thousand followers on Instagram. They wage their battle by spreading information about ‘forgotten plant species’ which can be used for food, but are not part of the mainstream knowledge.

“It is something very unknown but at the same time very close to all of us, even within the city,” tells me one of the founders, Marc Talavera, when I ask him why he thinks Eixarcolant is so popular. These plants are, in scientific language, ‘neglected and underutilized crops’ and they are two types. Wild edible plants, they grow alone, no one has selected them. And the selected ones, which local farmers have sorted out year after year for centuries (not accessible to large seed companies like Monsanto). They are all cultural heritage of the territory, not widely commodified or studied as part of mainstream agriculture. “We can all use them and no one can appropriate them,” says Talavera, who thinks their potential for study can play a significant role in changing the current food system.

I ask Monsonís what she thinks about the ability of cities to be, at least partially, self-sufficient in food production within their surroundings. I refer to a research study called AgroHiria on Productive Neighborhoods from the EHU/UPV School of Architecture in San Sebastian, Spain, and presented during URBANBATfest by Iñigo García, María Romeo, Ibon Salaberria y Jon Muniategiandikoetxea Markiegi. In the first stage of the study on ‘Feeding the City’ they concluded that it’s not always possible (or practical) to locally produce all the necessary food—meats, cheese, vegetables, fruit, spices—, even if a city lays on sprawling fertile farmlands. For instance, in the Basque country, small agricultural structures in the countryside produce almost without surplus, and have always been at risk of food precariousness.

They believe that cities need to find a middle way in between the current decentralized food system and Zero Km farming – a concept that assumes food comes from the same place it’s cooked and eaten, or at least food comes from under 100km away. “Collective farming cooperatives are sprouting out but it is a minority. We believe that they promote a new agriculture but they do not sufficiently reach consumers, and they do not contribute much to change the food system,” says Muniategiandikoetxea Markiegi. Their research points to solutions like “Vertical farms” or other urban productive systems that allow cities to be more sustainable in their food supply.

“I am not a very techno-positivist, although I don’t reject new technologies per se,” says Monsonís. “But there are terrible examples of techno-colonialism and technology can be very extractivist. Often low-tech or traditional solutions require less energy and can be very efficient. I am more focused on degrowth strategies, territorialized policies, changes in habits, and on the will of the political system to make changes of scale.”

“From an agroecological point of view, if we could eat zero-kilometer and season fruits and vegetables instead of food out of season which comes from very far away, we would be radically transforming our food systems. For example, we cannot eat lettuce every day. In terms of proximity, not everything has to be produced at Zero Km but find a reasonable scale.” A response to that in Spain is ‘La Red de Municipios por la Agroecología’ (translated ‘The Network of Municipalities for Agroecology’).

This network of technical staff and municipal officials, social movements and producers from member entities, work towards the implementation of innovative local policies for a productive and sustainable agri-food model that contribute to satisfying, locally, the demand for organic food and a healthy, fair and sustainable diet by its populations, in a context of sovereignty and food security.

Preparation and cooking time

During the festival, we tour across Bilbao with the well-known architect Patxi García de la Torre. We explore the architecture and food infrastructure that trace the historical development of the city. Old public bakeries, mills, water pipes, alhóndigas (warehouses for cereal, wine,…), food markets, slaughterhouses, candy factories, fishermen’s residences, streets dedicated to the food trade. But most of these buildings are repurposed or gone. Instead new spaces such as dark kitchens that occupy central places in the city for the production of fast food, the proliferation of food delivery companies, and transnational fast food franchise establishments are some of the symptoms of the current food system.

Monsonís grew up in the fishermen neighborhood of Barcelona, during its transformation for the celebration of the Barcelona 92 Olympics. She bemoans that the new urban architecture failed to emotionally reconnect its residents with the sea. All the knowledge about the local fishing culture was shared in common areas that were demolished. Today, Mediterranean bluefin tuna fattening farms and their logistics of distributing tuna around the world have contributed to the disconnection between what we eat from the sea and how we live by the sea. “Small initiatives like La Platjeta deliver baskets of local fish to customers who want to support local fishing in Barcelona,” says Monsonís.

She explores sustainable alternatives to eat from the sea, encourages buying ‘forgotten fish species’ with the proper legal size and studies the effects of extractivism of industrial fishing on artisanal fishing, marine ecosystems and the consequences on human lives on the different coasts. Precisely in her neighborhood of Barceloneta, these effects become really visible as many immigrants selling on the streets were former fishermen from Senegal. They came to Barcelona in search of better opportunities after their only way of subsistence was erased by industrial fishing in their waters. Monsonís also learns from their fishing culture interacting in community kitchens.

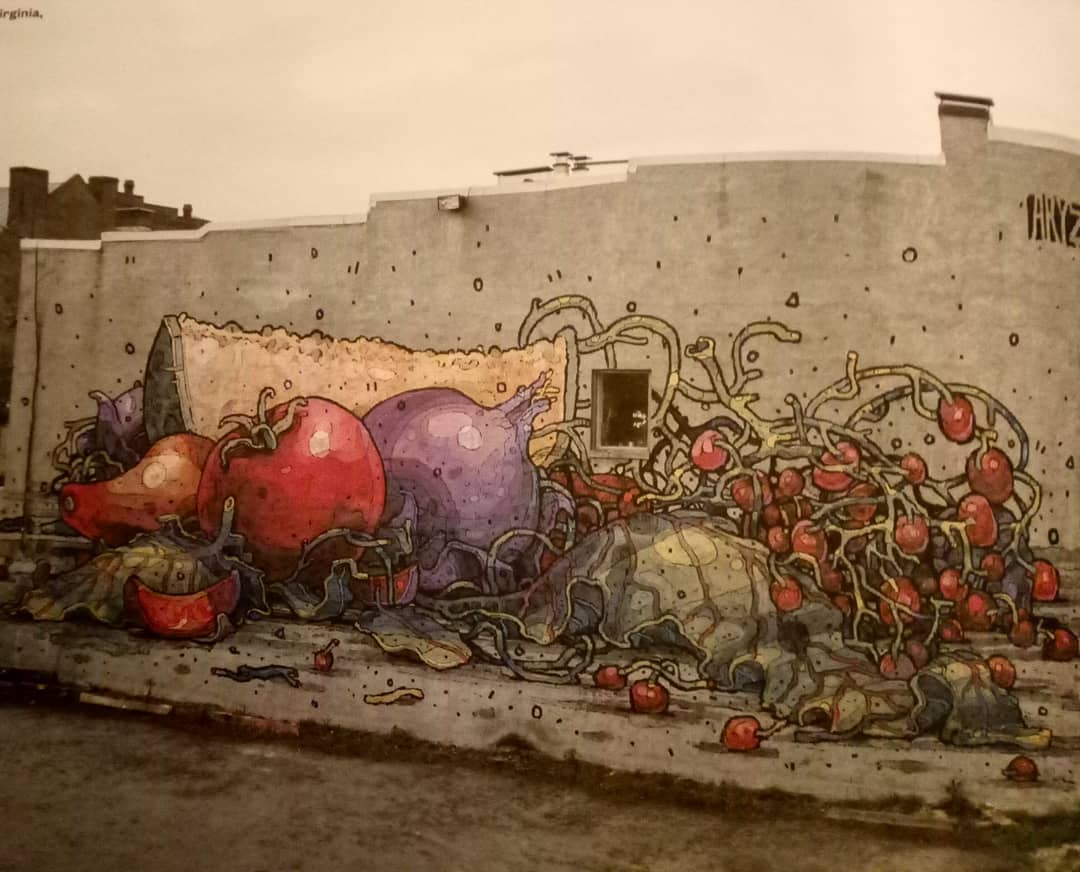

Monsonís’ interest to learn from the sea began over seventeen years ago after she was invited to a street art intervention in a marginalized neighborhood in Baltimore – a city whose port served as model for the port of Barcelona, she tells me. She spoke to people who live in ‘food deserts’ without access to fresh and healthy food. “They came up with recipes that their ancestors cooked but their culinary memory was almost lost due to the expansion of an aggressive food system,” she bristles.

Nutrition information

Monsonís says that, in agroecology, there is a lot of talk about scaling up. There are eating habits which can be changed at home, however there are many asymmetries that must be taken into account. Not everyone can afford to eat organic and agroecological, a distinction that Monsonís clarifies: “It may be organic but it comes from Brazil,” speaking from Spain. In order to be inclusive on a larger scale, political pressure must be applied, she claims.

“We are torn between everything and nothing, however I insist that we can make significant changes, although they are small, to not paralyze our influence. For example, urban gardens may not be the answer to supplying enough food to cities, they are rather places of socialization, of understanding, but they activate awareness, and connect people to the food cycle. We are damaging the planet, but at the same time we have agency and capacity to change things from that little something, looking for allies in the institutions.”

This week the UN has set certain targets within the COP28, including cutting methane emissions from livestock by 25%, halving food waste and managing fisheries sustainably by 2030. However, this roadmap is more focused on combating global hunger by building up on the current industrial food system. But “We have ploughed, fenced and grazed great tracts of the planet, felling forests, killing wildlife, and poisoning rivers and oceans to feed ourselves. Yet millions still go hungry,” writes George Monbiot in Regenesis.

While we are pushing for more radical proposals to address a flawed food system, it is very important, in Monsonís view, to continue building urban gardens, recovering lost lands, recognizing forgotten plants and fish, betting on agroecological crops, supporting traditional fishing, eliminating industrial meat, supporting shepherds, listening to popular vegan campaigners and understand that this is a difficult trip. “In order to create a viable transition to better food systems we have to meaningfully listen and understand the needs of the people who produce our food, and be on their side to ensure fair work conditions.”

“By rethinking how we feed ourselves in cities, we can actually create new imaginaries of how we want to live together in the future in this moment of polycrisis,” says Rodríguez Olea at the closing of URBANBATfest. “The city is inseparable from food. We need to generate new narratives and projects that transmit all this complexity.”

As we say goodbye, Monsonís tells me that she is expanding the concept of the MACBA’s kitchen to Berlin and Utrecht. Together, all these grassroots initiatives and changes in eating habits show how the smallest sign of personal activism could wield more clout than it might appear to transform our food system, and help us make peace with the planet.