Every month around 120 people head to the front desk of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library in Midtown Manhattan in search of a precious resource – other than the 400,000 books on its shelves. Smaller than books but not in their significance, free seeds circulate among New Yorkers thanks to the NYPL Seed Library located in that premises.

It is difficult to determine how big the impact of the NYPL Seed Library has been to cultivate green spaces in New York since its inception in 2018, but people who check out the seeds then share them with their roommates or fellow residents in their apartments or friendship circles. Ideally some of these urban dwellers would store their own seeds from the harvest and perpetuate the free exchange of seeds.

But this ideal world in the context of a city seems too far away. What is true, though, is that seed libraries and other seed banks are safeguards against food insecurity and biodiversity loss. Amid what the pandemic has taught us and a food crisis in front of our eyes due to the war in Ukraine, the global food supply chain feels more fragile than ever before.

One of the most common comments that senior librarian Emily Wejchert – in charge of the NYPL Seed Library – remembered hearing during the pandemic was “I live in New York City, there’s no place to grow!” When I met her at the library, she pointed out that with planning and the appropriate access to resources, people can have food forests within their apartments, homes and building complexes. But why are seeds so important?

Seed sovereignty and seed saving

Imagine you want to plant tomatoes on your balcony or on your windowsill. In the absence of a seed library in your city, you would have to buy the seeds to grow them. But it is actually your right to save, breed and exchange seeds out of your tomatoes instead of buying them every year, and “to have access to diverse open source seeds which can be saved –and which are not patented, genetically modified, owned or controlled by emerging seed giants.” Seed sovereignty allows you to produce your own seeds, also known as seed self-reliance. In the words of A Growing Culture, seed is power.

Understandably seed sovereignty is an important part to achieve food sovereignty among farmers, and urban dwellers if you will. However, this can be an incredibly frustrating experience when a crop is destined to grow seeds but then is lost because seed crops are a difficult process that requires the right skills and mostly proper timing.

Therefore, seed banks have increasingly become an invaluable resource, with a special connotation in concrete jungles dependent on food supplies, at a time of war, economic recession and a growing climate crisis. Imagine cutting food bills by growing your own fruit and vegetables or the most expensive food you like. Wejchert is ecstatic that members of the public who joined this seed-cultivating community have benefited so much from the seeds of the library in New York. “There has been a lot of sincere thank you’s from the community,” and she appreciates how vital trust in public institutions can be in terms of addressing basic needs in urban communities.

There are over 1,700 seed banks around the world that house vast collections of seeds for scientific research, protection of Indigenous cultures and species preservation in the most diverse places in the world. But the spread of seed banks across public libraries could one day prevent a food crisis in our cities.

There has been a lot of sincere thank you’s from the community

The NYPL Seed Library was created by Wejchert’s colleague Susen Shi thanks to her application for funds through a NYPL Innovation Grant awarded in 2018. Wejchert‘s interest in this type of library goes back to her graduate experiences at the State University of New York in New Paltz. As a student in the region, she heard about the Hudson Valley Seed Company, which is together with the Seeds Savers Exchange, the two best known nonprofit organizations and seed companies in the country.

One of the founders of the Hudson Valley Seed Company, Ken Greene, was a librarian in 2004 when he started the first seed library program in the United States. His goal was to introduce organic farming and sustainable agricultural practices to young people in its nearby community in Gardiner as well as in New York. “At the time I had been heavily involved in organic farming,” Wejchert reckoned.

Is the Seed Library Movement growing in the United States?

There is a history of seed libraries in the United States that inspired this project at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. It was a common practice that farmers in the country shared seeds to support each other and subsist with their harvest.

BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) communities have engaged in these practices for hundreds of years as a way of building resilience. For example, in Freedom Farmers, food justice scholar Dr. Monica White recounts a story that an enslaved woman from Africa attempted to maintain her people’s cultural roots by “carry[ing] the seeds of rice in her hair, unbeknownst to her captors.”

Eventually people moving to cities gave up that centuries-old practice. Yet, for more than a decade in this country, seed libraries as extensions of public library systems have been taking over that practice in an effort to revive it.

Since the first seed library in the Public Library in Gardiner, New York, seed libraries have spread around the country with the notable Cesar Chavez Seed Library at Oakland Public Library — “committed to increasing the capacity of our community to feed itself wholesome food by means of education that fosters community resilience, self-reliance and a culture of sharing” since 2012. There is also the seed library at The Potrero Branch Library in San Francisco, a grassroots project that was originally generated by community activists. In the latter, after people have harvested their crops, they save the seeds from the heartiest and healthiest of their harvest and return the seeds to the library for others to borrow.

So how exactly does the NYPL Seed Library in Midtown Manhattan work?

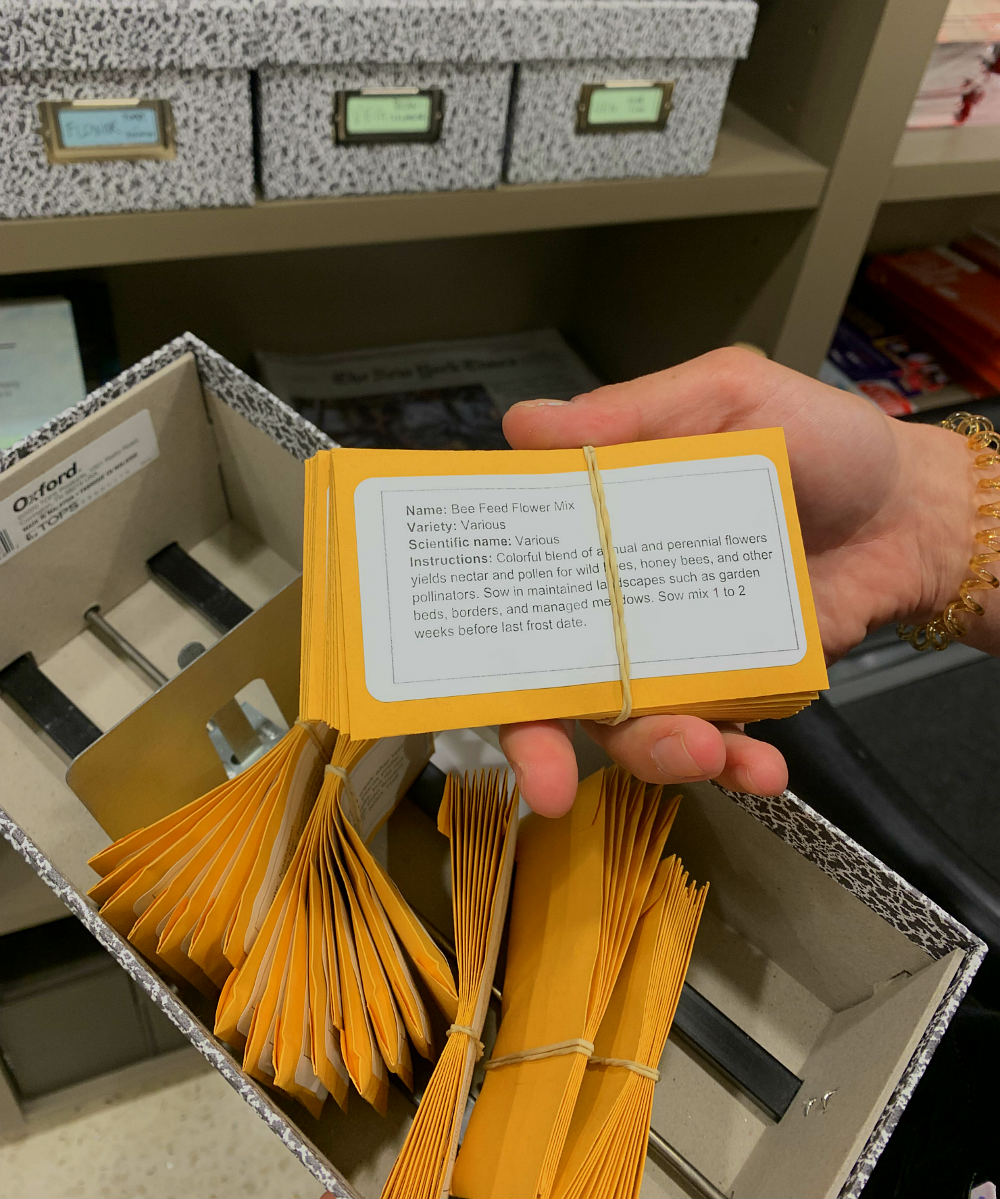

If you have a NYPL card, you are able to access a variety of free seed packets that are located behind the front desk of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library, where there is a QR code flier that points you to the virtual process of acquiring free seeds.

Seeds are organized in boxes showing the different varieties, sourced by the Seeds Savers Exchange. Wejchert is able to purchase seeds in bulk, and then work with other staff members to package them in easy-to-go packets.

By collecting data through online surveys, she noticed that some seeds (such as kale) will be more popular at times, however people’s tastes and interests tend to fluctuate. This helps her figure which seeds need to be replenished more than others in a given season. The most popular selections are herbs and pollinator plants (e.g. Bee Feed seed packets), but they also provide a litany of other seeds, including but not limited to beets, tomatoes, dill, catnip, marigolds, jalapenos, carrots, cilantro, and lettuce.

More than seed distribution to grow food

The main goal of the Seed Library, reads the NYPL website, is to provide “non-GMO, heirloom, and/or organic seeds, [so that the public can] grow vegetables, flowers, or herbs.” However, in our conversation Wejchert revealed that the Seed Library also focuses on something deeper: to inspire people with the resources to grow herbs and vegetables in their own home as a form of collective healing.

There is a sense of discovery, not to mention healing, that people were craving during the pandemic, and seed exchange gained momentum among neighbors. It helped to bridge the divide between communities and institutions and amplify, once again, the pressing issue of food security and the need to unlock fresh food for everyone, especially in cities, as a way to combat diseases and heal the planet.

Wejchert intends to host and facilitate public roundtables where she would like to bring together food activists to discuss the importance of food justice in terms of community access. Connecting those communities, she believes, is essential.

Even though the reach of this seed library is within Midtown Manhattan, the model could be easily replicated in other locations around the city – particularly in food deserts. For example, residents of the Bronx are considered to be 36 percent food insecure in comparison to the city average, which hangs at 16.6 percent. Wejchert hopes to expand resources into this area as a priority for the near future. The Brooklyn Public Library started a similar seed library but stopped during the pandemic and is still on hiatus.

“As we move through this century, libraries will have an important role in urban health.” In other words, Wejchert is confident that public libraries can help promote holistic health through the use of community gardens. “Increasingly our role [of public libraries], especially in an urban society, is to create paths of access for people to whatever goal they may have.” Public libraries are indeed one of the most democratic institutions in cities to fulfill that role.