Oddly, artist Claudia Barbera invites visitors to touch her art pieces and open them. Hanging on the wall, their form is of a triptych or altar piece, inside are the iconic images of the Virgin Mary in dark blue, Barbera explains, inspired by a color of mourning. They are made with the photolithography technique, drypoint and etching on cotton paper. On the panels of the triptych, Barbera creatively uses embroidery to allude pious practices of the Christian tradition, at times misused to excuse or condone abusive behavior and domestic violence.

Barbera, born crying in Chile in 1984 during the dictatorship, refers to her pieces as “traveling altars” which she can easily take anywhere to illustrate the struggle of women with the way religion represents them in a patriarchal society. The pillars of Barbera’s practice, ranging from feminism and teaching to activism and healing, are all present in her work “Putas Vírgenes” (translated “Virgin Whores”), and viewers are encouraged to create their own associations with religion and reflect on female behavior that does not conform to society.

In the same space, Barbera exhibits hand-embroidered textile pieces, made of a canvas material that reminds of a Holy Sudarium. They contain excerpts of anonymous stories told by women, who experience abuse, discrimination, domestic violence and confrontation with the patriarchal system. Barbera alienates the iconographies of the Virgin Mary with these disturbing reports by these women with religious backgrounds. All of these works are embroidered inside out, the idea being to show the imperfection, the secrets, the hidden and the taboo as opposed to what is accepted and correct. It prompts viewers to engage differently with femininity.

“I wanted to create an atmosphere that seeks to create a confrontation with our beliefs and myths about femininity. Our families, largely Catholic, were spaces full of censorship and silence. The image of the woman was submissive and compliant, and she couldn’t raise her voice if something happened to her because she would feel ashamed,” Barbera says. “There was like a quasi-conspiracy pact of silence. The iconographies of the Virgins in their altars are a symbol of the sacrifice of silence, one that nobody really knows what it is for.”

“I am a teacher and I have always worked in schools, and in that activity my students and teachers tell me their stories of abuse and domestic violence,” she explains. “I began the embroidery work in 2018 because I felt using its symbolism to give all of them a voice and open the dialogue to acknowledge that religious beliefs and teachings can serve as obstacles for victims of domestic violence or abuse. I think I discovered my voice in the stories of others.” Since then, the work pieces have wandered to different spaces in Valparaiso, from the public space at La Kioska curated by La Pan Galeria to cultural centers, and outside Chile, also holding healing workshops in Munich, Frankfurt and Barcelona to channel all the rage and aggression of the stories into energy for renewal.

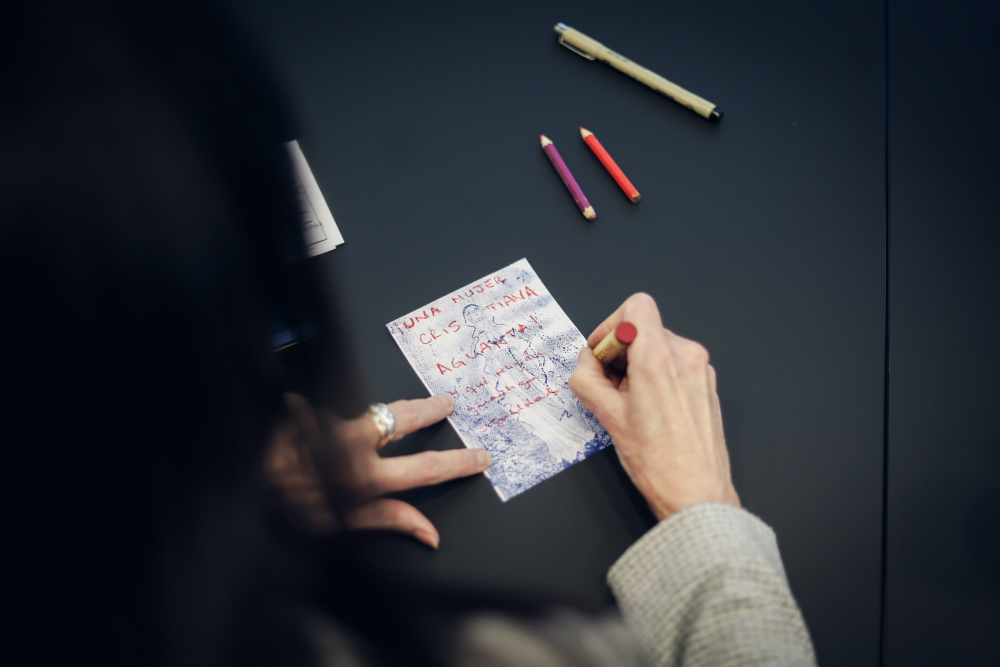

Barbera felt the need to complete her work by activating a healing process. In workshops people are encouraged to comment or tell their stories in postcards or via email and send them to Barbera, who artistically intervenes with some of them. The postcards become part of the exhibitions inviting people to connect with each other. They are displayed around altars made of sculptures with a lighted candle, to confuse the visitor at first glance, but then provoking a reaction to the profanity of its composition – the virgins have the form of vulvas although “many people don’t want to acknowledge it,” says Barbera.

The relationship between religion and domestic violence is the elephant in the room and neither public institutions nor policymakers and practitioners want to touch it to finally instigate a discussion about this difficult topic. The remarkable work of Barbera embraces it impressively in an artistic and performant way but it hasn’t always been easy for her to navigate cynicism. “Until now I haven’t received any support from a government sponsored cultural institution in Chile to display my work,” she says. She grew up in a Catholic family, and the contradictory and ranges between innocence and original sin in religion are specially present in Chile, but also in America as a whole.

The images of the Virgins correspond to real holy characters that Barbera photographed during her visits to churches in Quito, Ecuador, highlighting the syncretism between the Catholic religion and the pre-Hispanic indigenous culture which evolved into the artistic movement of “Escuela quiteña” (translated “The Quito School”). Barbera tells me about the particular significance of the Virgin in America due to the Spanish colonization. “The figure of Jesus didn’t work as well as the image of the Virgin. The Spaniards took advantage of her divinity and pure dignity to colonize the natives who associated her with mother nature, the sea, the stars, what they called deities, because according to their beliefs, a God who produces spiritual children can only be a mother from heaven.”

Another aspect that I greatly appreciate in Barbera’s work is the symbolism of embroidery and sewing, whose teaching has always been transmitted in a matrilineal way and, according to Spanish writer Irene Vallejo, has played a crucial role in storytelling and the transmission of knowledge. While sewing, a task exclusively feminine in the past, women told their stories and so much so that there are still traces of it in the language: the thread of a story or the distaff side (the maternal branch of the family).

In her recollection of stories, Barbera was specially touched by a woman who believed that everything that happened to her was her fault and not her husband’s who abused and mistreated her. Her religious community demanded that she return to that marriage, because otherwise she would be left alone, without support networks, without family or friends, so deep down that she had no escape.

In fragile conservative settings or with high religiosity, communities often fail to adequately respond to the needs of female victims of domestic violence. For the artist, Virgins create this double image, of the holy woman and the whore, or the good woman and the libertine. She believes it is up to women to choose which one they want to be, but always exercise their freedom of choice about sexuality, abortion, including ending domestic violence at the hands of their partners.

To May 20, 2023, Amerikahaus.de

Find out about our latest stories first – follow @theurbanactivistcom on Instagram